Houseboating

Cruising Houseboats

This fast, sporty, luxurious craft satisfies many demands. People of wealth and expensive taste like cruising houseboats for their mobility and their speed, which is sufficient to tow water skiers. Housewives like them because the boats have all the conveniences of home.

The typical cruising houseboat differs markedly from other powerboats. The latter are designed for speed and seakeeping qualities, with accommodations force-fitted into streamlined and seaworthy hulls. The result can be cramped quarters, small galley and toilet rooms, and curved decks and walls.

Cruising houseboats, on the other hand, have plenty of living space, huge windows, flat decks, and squared rooms - exactly as in a house. These houselike qualities, however, reduce seaworthiness. The boxlike, shallow-draft hull can be difficult to manage in rough water, the large superstructure is vulnerable to strong winds, and the lightly constructed walls and large glass areas cannot withstand breaking seas. However, there are some hybrid models in which large, squared rooms are set into cruiser hulls, making them relatively seaworthy vessels.

Among the unnautical luxuries to be found on cruising houseboats are picture windows, drapes, standard beds, wall-to-wall carpeting, and complete kitchens with apartment-size stoves, refrigerators, and sinks. Even small houseboats have fairly large interiors, porches for and aft, and flat roofs for sunning. On a few models the sleeping space, typically for six or more, can be doubled by unfolding on the top deck a built-in tent with self-contained bunks.

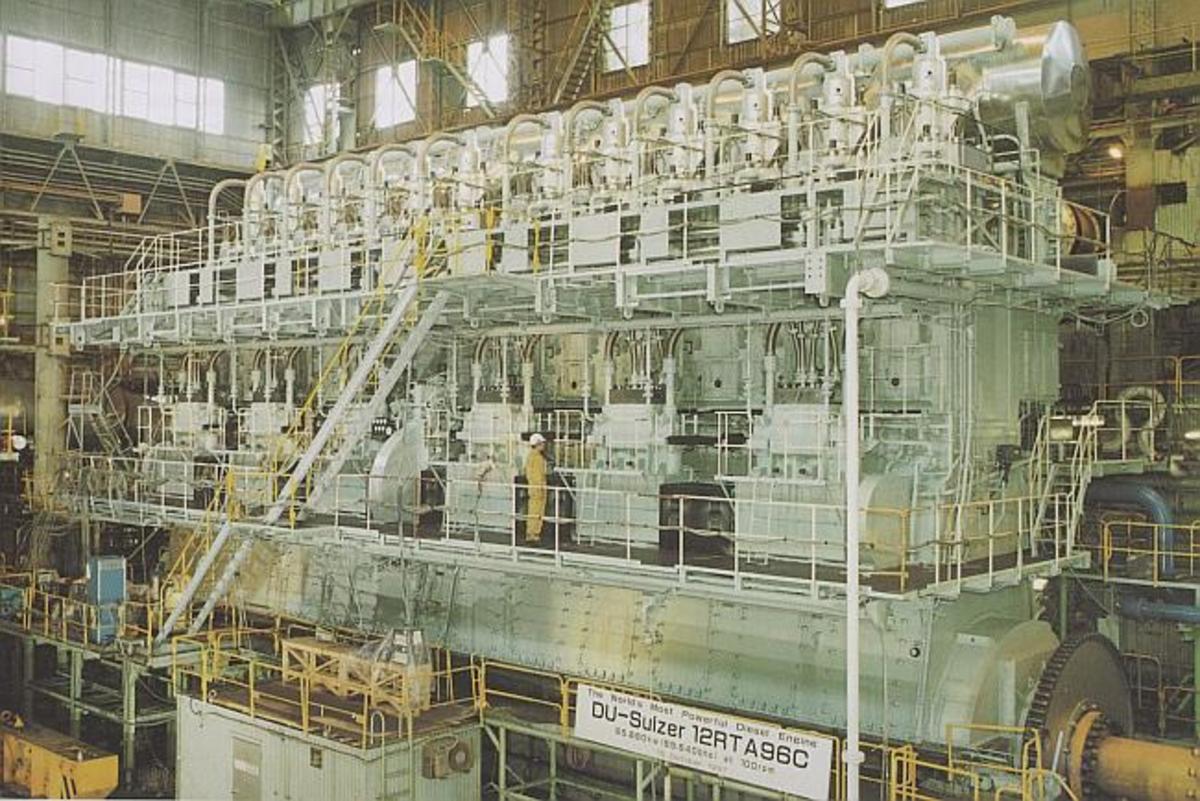

Cruising houseboats are propelled by one or two high-powered outboard motors, or by inboard-outdrive. The latter, also called stern-drive, consists of one or two powerful marine engines permanently emplaced within the hull, their drive shafts piercing the stern transom above water level and connected by vertical links to the propeller shafts. When the boat passes over a shoal, the propeller assemblies tip up undamaged, as an outboard motor does. Inboard engines range from 60 to 325 horsepower each. They are generally larger and longer-lived than outboard motors, but more expensive.

Jack McKee, a boatbuilder of Gallatin, Tenn., is credited with the idea for cruising houseboats. In 1960, when the small outboard motor broke on McKee's 30-foot (9-meter) fiberglass houseboat, a friend attached a 50-hp outboard, and the houseboat, surprisingly, planed like a speedboat.

Demand for cruising houseboats was so great that for years McKee's firm was unable to meet it. By 1970 there were some 50 other manufacturers in the United States building cruising houseboats of steel, fiberglass, and aluminum, in lengths from 18 to 55 feet (5 to 17 meters). Inside, they look like house trailers, and many builders make both. Some cruising houseboats are mated to trailers so that they can serve as mobile homes afloat or ashore.

The cost of a cruising houseboat, varying with size, is roughly comparable to that of a lightly built vacation house. Because of their square lines, the boats cost about one-third less than other powerboats of equal length. Houseboats for rent are becoming common at many marinas in the United States and Canada.

Floating Homes

In cities where residential land is scarce and there are calm backwaters, particularly in Asia, there are great colonies of houseboats. Hong Kong and Singapore have floating cities of them, rafted together and covering broad areas of water. In the Cholon quarter of Saigon, South Vietnam, is the Chinese Arroyo, crowded with houseboats inhabited by Chinese.

The banks of the Nile River near Cairo are lined with luxurious houseboats in which well-to-do Egyptians escape the summer heat. The Vale of Kashmir is famed for its houseboats, first built there by Britishers because foreigners were forbidden to build houses in the Vale.

In the United States there are flotillas of floating homes in the waters around Miami, Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco and at many places in the Mississippi River basin. Some are elaborate structures, two or three stories high, with more room and comfort than conventional apartments. Festooned with gay awnings, potted flowers, and flags, and with small boats slung from davits, they radiate a holiday atmosphere.

Most American houseboats, however, are one-story dwellings of two to four rooms. Where winters are temperate, houseboats are permanent homes. Where winters are severe, they are usually vacation homes. Many look exactly like houses ashore except that they are on floats.

In earlier times the lone houseboater in his bayou was independent and self-sufficient. Increased numbers of houseboaters, however, caused problems, such as water pollution, and a need for health and safety standards and police protection. New houseboaters also wanted benefits such as connections to city electrical, gas, water, telephone, and sewage systems; garbage collections; and mail, package, and grocery deliveries. Many houseboat colonies are therefore closely integrated with adjoining communities. Seattle, for example, had an estimated 5,000 people living in houseboats in 1969. Most house-boaters rented dock space from private owners, although a few owned a bit of shoreline. There were some incorporated groups of a dozen or so houseboaters who jointly owned a dock, utility connections, and a parking lot for their cars.

Floating homes are usually without engines, but the houseboater who grows restless can disconnect his utilities, cast off his dock lines, and tow his home to bluer waters.

History of Houseboats

One of the earliest known types of houseboat was the thalamegus, a luxuriously appointed barge with cabins for a large company. Egyptian nobles used such boats on the Nile at least 4,000 years ago. Cleopatra, decked out as the goddess of love, had herself wafted up the Tarsus River to Tarsus (in modern Turkey) on her thalamegus to meet Mark Antony.

In Hong Kong, the Tanka and Hoklo peoples have dwelt in houseboats since prehistoric times. These houseboaters seldom marry shore dwellers. The Hong Kong government estimated that in December 1962 there were 46,459 people living on houseboats there, although a typhoon had wrecked hundreds of boats a few months earlier.

In the United States between 1787 and 1880, hundreds of thousands of migrant families drifted west and south in houseboats on the Ohio and Mississippi river systems to setde the central and western United States. At the head of navigation on many rivers they built houseboats of several types, often of timbers thick enough to be bulletproof. Each boat was large enough to shelter a family with all its possessions and livestock. In the main cabin was all the furniture and a fire for cooking and warmth, since the journey might take months. There was a long steering oar and perhaps a sail or a pair of long oars, called "sweeps," to help maintain course. At times the houseboats floated downstream in convoys, for protection against Indians and river pirates. Finding a desirable homesite, the family broke up the boat and built a home with the wood.

Cabins were built on flatboats that carried agricultural products to be "sold down the river," where the boat was also sold for lumber or fuel. Abraham Lincoln in his youth was a crewman on two such 1,000-mile (1,600-km), 3-month trips from Ohio to New Orleans.

Many persons made their permanent homes on boats, earning their way on the rivers or living on fish and game. River traffic diminished, and the people who stayed on the rivers were generally poor. Most of their craft, called shanty-boats because of their crude construction, stayed at the same sites until they sank. Colonies of shantyboats existed for generations around Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Louisville.

When drought and depression devastated the central United States in the 1930's, thousands of families built themselves shantyboats. They got away from rent, taxes, and bill collectors, and lived by fishing and hunting. These boats have generally disappeared, but many Midwestern sportsmen still have crude houseboats which they call shantyboats, staked out in a river as a retreat from the pressures of daily living.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2009 Bits-n-Pieces