"MURDER" ON THE ARCTIC BARREN LANDS

This Hub describes an extraordinary experience that I lived over 40 years ago--in one of the most desolate areas on planet Earth. This experience faded into my personal memories decades ago, but for reasons unknown, it has now returned to my thoughts, day after day. I think I’m supposed to share it. And what better audience than here, with my fellow Hubbers?

WHY THIS ZANY ADVENTURE HAPPENED

In 1968 my good friend, Roy Duggan, and I spent almost five months—May 1 to September 15—living in a canvas-and-plywood tent on the Barren Lands (popularly called “the Barrens”) in Canada’s Arctic. We built our camp on the shore of an unnamed lake close to the end of Bathurst Inlet, a thin southward slash in the coast of the Arctic Ocean, about 350 miles ENE of Yellowknife, capital of the Northwest Territories. The Arctic Circle was only a mile or two from our camp..

Now, you might well ask, what in the name of sanity were we doing in a forlorn deep-freeze where temperatures of 55º below zero are common, the screeching bone-numbing wind almost never stops, the landscape is a bleak sameness of black rocks and endless lakes, and the lake ice is over six feet thick? Add to all this the complete isolation and the loneliness that goes with it, and you have one of earth’s most formidable, most frightening, and most dangerous environments. Why were we there?

You guessed it—money!

SERVICING MINERAL CLAIMS IN CANADA

An acquaintance of ours owned mineral rights to over 650 mineral claims in the Bathurst Inlet area. To retain mineral rights in Canada in 1968, the “owner” of the rights had to (a) post a $100 bond per claim per year or (b) “trench” or physically remove one cubic yard of material per claim per year.

In 1968, it was a hell of a lot cheaper to send Roy and me into the Barrens with some tents, some food, a WW II rifle, a revolver, a few drums of explosives, and a case of blasting caps, than it was to give the feds $65,000. The fact that we didn’t know TNT from TSP, had zero experience in the deep Arctic, and were stupid enough to go on this adventure in spite of our ignorance, just seemed to quicken our acquaintance’s interest the more. You had to know the guy. . . .

SOME REALLY INTERESTING STUFF ABOUT CANADA’S BARREN LANDS

Canada’s 9,985,000 sq. km make it the second largest country in the world. Of that land mass, the Barren Lands comprise about 40%--an area so vast you could stuff France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, Greece, Turkey, Sweden, and Ukraine into the Barrens—and still have 200,000 sq. km left over for your larger barbecue parties.

A few hundred million years ago (give or take), successive advancing and retreating ice ages scraped down what is now central Canada, leaving level prairies in the South, and the Barrens in the North. The Barrens are a seemingly limitless, stark, treeless landscape of boulders, grasses, and small shrubs, a land deeply scarred and gouged by the retreating ice into over a million lakes and ponds of every size imaginable, most of them pristine and unnamed to this day. Canada has more water than any other country on Earth..

Many areas of the Barrens are so clogged with heavy marsh and peppered with so many lakes that travel even with today’s high-tech amphibious vehicles would be extremely difficult, and with the heavy bone Inuit dog-pulled sleds of past ages, travel would have been impossible.

So, it is reasonable to suggest that human beings have neither settled nor hunted nor travelled through these impassable areas—ever. Local Inuit stories, oral traditions, and more recent written records make mention of no travel by Natives or Europeans through these unmarked and unknown marshy areas.

Put briefly, Roy and I set up camp where, in all likelihood, no human being had ever been. We might as well have located on the surface of the moon.

THE PURITY OF THIS DESOLATE LANDSCAPE

Every day we were awed by the utter purity of our environment. Breathing deeply was an experience. The odorless air would almost cut into the tissues of your lungs. The lake water, numbingly cold and free of any contaminants, had an indescribably sweet taste. When we finally got through the ice (how is another story, another time. . .) we routinely caught 3-lb. lake trout with beer can tabs and hooks—no bait, just a tab and a hook on a jig line. They’d never been fished, so they’d strike at the flash alone. And we were privileged to happen upon a herd of musk oxen, which snuffled and snorted and whirled about and behaved pretty much the way you’d expect bewildered creatures to behave in the presence of aliens.

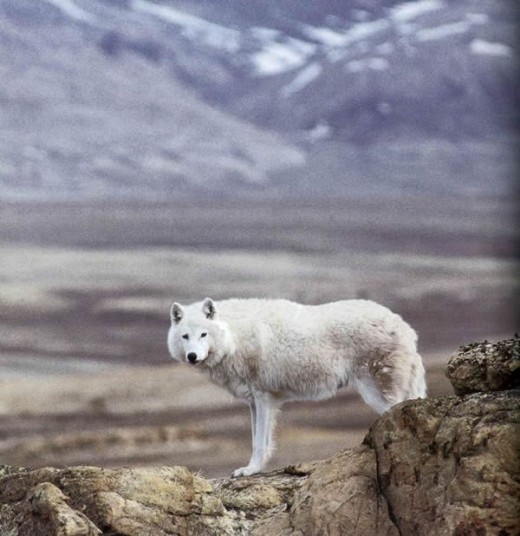

And then there were the wolves. One day, a female Arctic Wolf visited our camp. Pure white, unafraid, curious, she sniffed around the entrance to our supply tent, stared at Roy and me with languid curiousity, and then glanced quickly down at the lake ice. We glanced with her. And there, pacing back and forth on the ice like any annoyed husband waiting for his wife, was her mate.

After a few minutes of agitated pacing, he gave a single short bark. The female, now no more than twenty feet from us, cast a final look at the supply tent, then padded through the snow to his side and they set off down the middle of the lake.Over five minutes later we could still see their dim shapes in the fading silver light half a mile away, but in the absolute silence we couldl clearly hear the soft crunch of their paws on the ice of the lake.

There were many more experiences, many more revelations and epiphanies that impressed upon us the rare privilege we enjoyed as intruders in this unsullied environment. Occasionally, we were called upon, not to enjoy, but to suffer as intruders. I mentioned earlier that the wind blew virtually all the time Not gale force, but briskly. This "wind routine" was a constant, until one very warm day in mid-July. Roy and I were slogging through the grass towards our camp, about half a mile away, the wind strong in our faces. Suddenly, the wind stopped. Dead air. First time in over two months. Immediately, the AIR went black! The sky directly above us was blue; the sun directly above us was shining , but we were enveloped in a thick black , choking cloud of. . .mosquitoes ! Billions of them rose up out of the muskeg, their fragile bodies finally able to fly in the still air. They were in our mouths, eyes, ears, up our pant legs and shirtsleeves, covering all our exposed skin as we ran for the safety of the tent . Once zippered inside, we took savage joy in squashing the little bastards that came in with us.

Next morning, we put on bug netting before we ventured outside!

Among these many extraordinary experiences that Roy and I had in this harsh and hauntingly beautiful environment, the one that prompted me to write this Hub happened to me alone one afternoon in late July.

A SHOCKING FLASH ON THE HORIZON

At that time of year the Arctic sun literally does not set. It dips half-way below the horizon, runs along for a while, then gradually starts to rise again. Quite eerie for someone from southern climes, programmed for the impending darkness that doesn’t come. On this day, I was surveying some claims, walking away from the sun, which was a couple of hours away from the horizon. Suddenly, a blinding white flash on the horizon in front of me. I stopped, shocked. Again the flash, and so crisp and bright and defined, it had to be man-made. But that wasn’t possible—our camp was behind me and no other people were here! The only way in was by plane, and there hadn’t been so much as the sound of a plane for weeks. Another flash—even brighter! Apprehensive, my heart pounding, I nonetheless started to move towards it. I figured it was maybe a mile away. As I moved, dodging around ponds and otherwise shifting my line of travel in response to the terrain, the light would flash, sometimes in rapid blinks, sometimes in longer bursts. I slogged through the muskeg more rapidly, my heart racing, fear making my sweat acrid and unpleasant.

What would I find? In one grisly fantasy I saw the flash become a bayonet plunging into my chest. The next instant, I remembered a tale my father had told me about how a python could hypnotize a monkey to walk into the snake’s gaping mouth. I felt like that monkey, but—again a flash! And another! But I couldn’t stop walking towards it, mesmerized.

I struggled up a short rise, prepared for whatever fate waited for me there. I had taken my knife from its sheath and held the blade in front of me to scare the homicidal maniac who had (undoubtedly) parachuted in expressly to dismember me slowly and throw my twitching body parts to the wolves.

]Down on my knees now, I mustered my waning courage and thrust my head over the lip of the rise. . .and there it was.

CONFRONTING MY ENEMY

On a bed of solid rock, facing me squarely, stood a three-foot high column of exquisitely beautiful brassy-gold rock, composed of hundreds of thousands of facets reflecting the rays of the sun in flashing stabs. I abruptly sat down in the wet marsh, oblivious of the cold and damp, almost crying in the aftermath of fear. I felt like a weak fool, but realized in the next moment that my fear arose from our extreme isolation and my absolute conviction that the “unnatural” flashes could only have been a terrible threat.

Still weak in the knees, I struggled to my feet and slowly walked around my “enemy”, marveling--now!--at the interlaced beauty of its structure. The column, more like a cone, really, was about six inches in diameter at the top, two feet at the bottom. The thousands of pieces, some tiny specks, some rectangles three inches by one inch, were all dazzling—as though carefully polished by human hands, then painstakingly glued into the column’s present form.

I’m no geologist, but I was sure the column was iron pyrite, commonly called “Fool’s Gold”, and given the debilitating emotional fantasies I’d just put myself through—very aptly named.

Even though the "rock" in the photo below is only the size of a very large egg, its structure and appearance accurately depict the larger column of glittering rock I confronted that day on the Barrens. You can imagine the reflective power of the countless thousands of facets, when hit by the rays of the sun.

Originally, the column of gleaming iron pyrite would probably have been sheathed in sedimentary rock.With infinite slowness, millions of years of wind had ground the rock away to reveal this beauty and leave it as an ancient sentinel on the Barrens.

MAN’S INHUMANITY TO “NON-MAN”

I pulled a sandwich and a thermos of tea out of my pack and sat by my sentinel to eat lunch. I looked at “him” often; I talked to him, but he had no words for me. When it was time to go, I stood up and said goodbye and then. . .I’ll never know why I did it--I reached out with the toe of my boot, and touched him.

Instantly, the entire column—with a light, casual tinkling that sounded like ten thousand glass dominoes tipping each other—the column collapsed in a heap at my feet

I stood there, stunned, my boot paralyzed in space, my jaw hanging like a stupid gate. Millions of years in the making. Gone in five seconds.

I felt like a murderer.

I have no resounding conclusion to offer, no timeless truth to expound. Blathering on about the fragile balance of nature and man’s willful thoughtlessness would be cliché and silly. I will say that I felt deeply saddened, that I felt I had betrayed an implicit trust between this vast and amazing place and myself as temporary custodian of a tiny part of it.c.

And so this, I suppose, rather pointless story comes to an end. From this side of my silent relationship with you, my reader, it feels good to have got this bit of my life on paper. And from your side of our silent relationship, well, only you can assess what my story might mean to you. At minimum, I hope you enjoyed it!..