"I Know It When I See It": Judge Roy Moore, the Federal Courts, and Religion

After the Supreme Court made the colossal blunder of thinking they could decide what constitutes “pornography,” Justice Potter Stewart is said to have quipped about pornography that he would no longer attempt to define it, but said “I know it when I see it.”

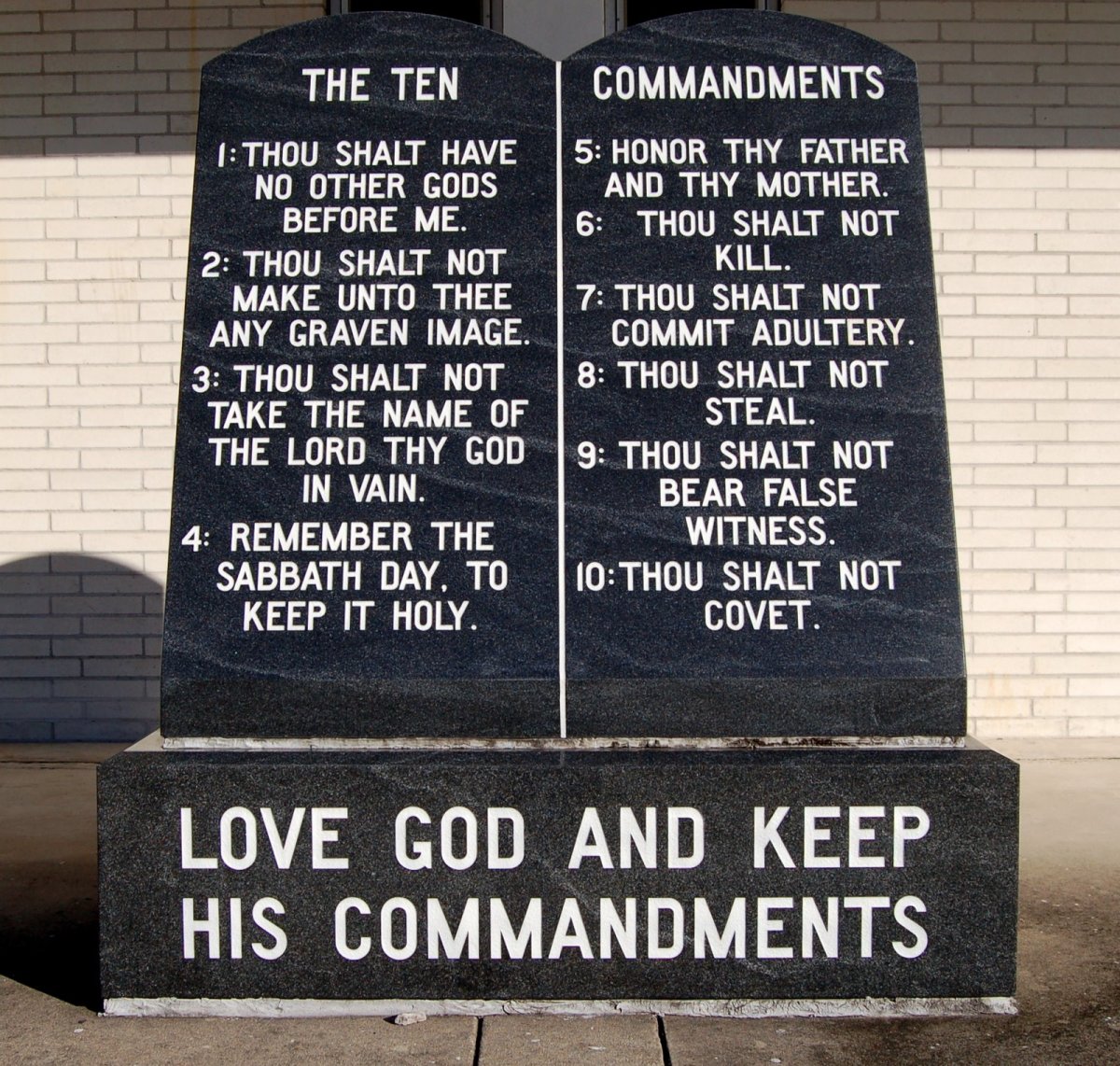

“I know it when I see it”, still a favorite anecdote in Supreme Court folklore, has also become an anchor of American jurisprudence. Forget the “Lemon Test” or the “Sherbet Test”, today we have IKIWISI: the “I Know It When I See It” Test. The IKIWISI (pronounced ee-kee-wee-see) Test is nowhere better illustrated than in the case against Judge Roy Moore when he was ordered, but refused, to remove a Ten Commandments Monument from the Rotunda of the Alabama Supreme Court.

In my first essay on Judge Roy Moore, I gave an overview of the events surrounding Moore’s controversial Ten Commandments monument, the firestorm that ensued, resulting in his dismissal from office. However, Roy Moore has returned to the limelight as he seeking his old position as the Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. In my second essay, I discussed a few principles important to Moore’s Ten Commandments stand that are important for us to know today. In this essay, I would like to talk about how the courts are undermining the rule of law and inviting judicial tyranny by refusing to be bound by the meaning of language.

Judge Moore and the Establishment of Religion

In my last essay, I mentioned that our courts have abandoned the idea that America is a “nation under God” for a belief that says that to acknowledge God in government is a violation of the Constitution. We should not be surprised that judges arrogant enough to dismiss God will have no problem dismissing the founder’s Constitution. This is nowhere more evident than in the case Glassroth v. Moore where former Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore was accused by the federal courts of “establishing a religion” because he had placed a monument of the Ten Commandments in the Rotunda of the Alabama Supreme Court building. The judge in the case, Myron Thompson, ordered Moore to remove the monument, an order Moore refused to obey and was drummed out of office as a result.

In order to know whether or not Moore was “establishing a religion,” a definition of “religion.” is in order. According to Moore, “religion” is "the duties we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging those duties." Federal judge Myron Thompson, who presided in the case against Moore, said that Moore’s definition was “incorrect and religiously offensive.” Where did Moore get this definition of religion that was so offensive to a federal judge?

Moore’s definition was a derivation of one that was used by the nation’s founders. George Mason probably originated it and it shows up in his Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) and James Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785). In fact, the Court accepted a variant of the definition as the constitutional definition of religion in Davis v. Beason (1890).

Obviously, if the judge found Moore’s definition of religion “incorrect” and “offensive” he had his own definition in mind. That’s where the second problem arises: not only did Thompson reject a definition of religion that was common at the time of the drafting of the Bill of Rights, he also provided no definition of religion at all. In Thompson’s words,

the court lacks the expertise to formulate its own definition of religion for First Amendment purposes. Therefore, because the court cannot agree with the Chief Justice's definition of religion and cannot formulate its own, it must refuse the Chief Justice's invitation to define ‘religion’.[2]

According to Thompson, the court lacked the ability to define religion, yet, it accused Moore of establishing one. Apparently, Thompson’s credo is that he does not know how to define religion, but he “knows it when he sees it.”

Greek Gods and Religious Establishment

Putting aside Judge Thompson’s IKIWISI jurisprudence for a moment, was Judge Moore “establishing a religion” by placing that Ten Commandments monument at the Alabama Supreme Court building? Not according to the original understanding of the Constitution. An “establishment of religion” during the founder’s time was a state church. The meaning of the Establishment Clause was that Congress was not to prefer one state Christian denomination over another.

In his book So Help Me God, Moore demonstrates how absurd Thompson's understanding of “establishment” was by referencing a likeness of the Greek goddess Themis that was outside the federal courtroom building where his trial was taking place:

…There’s a Greek goddess [out front] and I think it does not represent our form of government, and I think people can feel very strongly about that. But it doesn’t make it constitutional or not constitutional. What makes it constitutional or not constitutional is whether or not it’s the establishment of religion under the First Amendment. [3]

Moore rightly stated that even if people regarded the Greek goddess likeness as an “idol” and worshipped it as they went by, the likeness of Themis would still not constitute an “establishment of religion” because that is not what the “establishment of religion” means. It may be that Judge Thompson’s opinion that the Ten Commandments monument constituted an establishment of religion, but opinions are not law. And when a judge ignores the clear meaning of the Constitution and substitutes his own meaning, then we no longer are under the rule of law; we are under the imaginations of judges.

Conclusion

In summary, Moore was told that his Ten Commandments monument was an establishment of religion. When called upon to give a definition of “religion,” the court refused to define it even though there was a historical definition dating back to the time of the Bill of Rights.

It’s time for an empathy check: how would you like to be accused of a crime that the court could not define? Do you have a problem with this? You should. If a judge will not state his definition of a legal concept, he will not be bound by the language of the law, but only by his imagination. Words in this case do not provide limits to the judge; rather they become the tools of his imagination. And if he is using his imagination as a rule, you are no longer under the rule of law. You are subject to the musings of the magistrate. Such abuse may not be easy to spot, but I hope that after reading this essay, when it comes to matters of judicial tyranny, you will be able to more frequently say, “I know it when I see it.”

Sources

[1] 229 F. Supp. 2d 1067 (M.D. Ala. 2002). http://www.morallaw.org/PDF/glsrthmre111802opn.pdf.

[2] 229 F. Supp. 2d 1067 (M.D. Ala. 2002). http://www.morallaw.org/PDF/glsrthmre111802opn.pdf.

[3] Roy Moore: So Help Me God: The Ten Commandments, Judicial Tyranny, and the Battle for Religious Freedom (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2005), 185.