What Is Sharia Law—and Why It Struggles to Integrate with Western Civilization

Sharia law, a term that often evokes polarized reactions, is far more intricate than its popular portrayals suggest. Rooted in centuries of Islamic jurisprudence, Sharia is not merely a legal code but a comprehensive moral and spiritual framework that guides the lives of millions of Muslims around the world. It encompasses everything from daily rituals and ethical behavior to complex rulings on marriage, finance, criminal justice, and governance. For many adherents, Sharia represents divine wisdom—a sacred path toward justice, discipline, and communal harmony.

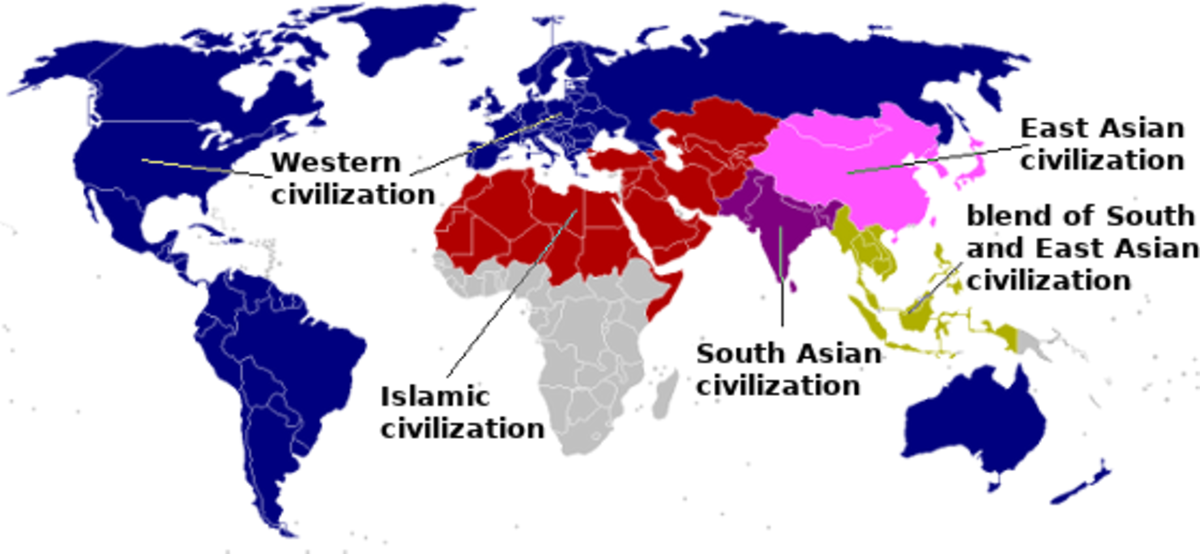

Yet despite its spiritual significance, the implementation of Sharia law in contemporary societies—particularly those shaped by Western democratic ideals—raises profound and often contentious questions. Western civilization, with its emphasis on secular governance, individual liberties, gender equality, and freedom of expression, operates on principles that can diverge sharply from those embedded in traditional interpretations of Sharia. This tension is not merely theoretical; it plays out in debates over religious accommodation, legal pluralism, and the boundaries of cultural integration.

As global migration and multiculturalism continue to reshape national identities, understanding Sharia law in its full complexity becomes essential—not only to foster informed dialogue but also to navigate the delicate balance between religious freedom and universal human rights. The challenge lies not in demonizing or romanticizing Sharia, but in critically examining its role within pluralistic societies and asking: where do sacred tradition and civic modernity converge, and where do they collide?

Where Sharia Law and Western Civilization Diverge—And When Tensions Escalate

Western civilization, particularly in its legal and political institutions, is anchored in a constellation of values that prioritize the individual: personal autonomy, secular governance, gender equality, freedom of speech, and the rule of law. These principles form the backbone of liberal democracies, where laws are shaped through public discourse, elected representation, and constitutional safeguards. In contrast, Sharia law—when implemented as state law—derives its authority from divine revelation and religious tradition, often placing communal religious obligations above individual liberties.

This fundamental difference in origin and orientation creates several areas of tension:

1. Theocratic vs. Secular Governance

Western democracies are built on the separation of religion and state. Laws are debated, amended, and repealed through democratic processes, reflecting the evolving values of a pluralistic society. Sharia, however, is considered by many Muslims to be divinely ordained and therefore immutable. In states where Sharia is codified into national law—such as Iran or Saudi Arabia—religious scholars often hold significant judicial power, and legislation is interpreted through religious doctrine rather than civic consensus. This rigidity can hinder reform and limit the scope for democratic reinterpretation.

2. Human Rights and Gender Equality

One of the most contentious areas is the treatment of women and minorities under certain interpretations of Sharia. While many Muslims advocate for gender justice within an Islamic framework, traditional rulings may include:

-

Unequal inheritance laws, where daughters receive half the share of sons

-

Restrictions on women’s legal testimony, which may be valued less than men's in court

-

Limited rights in divorce, custody, and mobility

-

Corporal punishments, such as flogging or stoning for adultery

-

Capital punishment for apostasy, or leaving the Islamic faith

These practices conflict with Western norms of equal protection under the law, bodily autonomy, and freedom of belief. International human rights organizations have repeatedly raised concerns about such laws when enforced by the state.

3. Freedom of Speech and Religion

In liberal democracies, individuals are free to critique religious institutions, change their faith, or abstain from religion altogether. Sharia-based legal systems, however, often criminalize blasphemy, heresy, and apostasy. In countries like Pakistan or Iran, blasphemy laws have led to imprisonment, violence, and even death sentences for those accused of insulting Islam or the Prophet Muhammad. This suppression of dissent undermines the pluralism and open discourse that Western societies strive to protect.

4. Legal Pluralism vs. Uniform Law

Western legal systems generally uphold a single, secular framework that applies equally to all citizens, regardless of religion. While religious practices are accommodated privately—such as dietary laws or religious holidays—public law remains neutral. In contrast, integrating Sharia into national law can create parallel legal systems, where citizens are subject to different rules based on their faith. This can lead to inconsistencies in justice, especially in family law, inheritance, and criminal proceedings, and may erode national cohesion.

These tensions do not imply that Islam or Sharia are inherently incompatible with Western life. Many Muslims in the West live by personal interpretations of Sharia that emphasize ethics, charity, and spiritual discipline without seeking to impose religious law on others. The challenge arises when Sharia is politicized—used not just as personal guidance but as a framework for state governance. In such cases, the friction between sacred tradition and civic modernity becomes difficult to ignore.

While many Muslims in the West practice Sharia as a personal ethical guide—focusing on prayer, charity, and moral conduct—there have been instances where individuals, including some refugees, have attempted to promote or enforce stricter interpretations of Sharia law within their communities. These efforts, though often rooted in religious conviction or cultural preservation, can sometimes lead to unsafe or legally problematic situations.

Examples of Individual Efforts and Their Consequences

Here are a few documented cases and patterns that illustrate how individual promotion of Sharia law has led to tension or safety concerns in Western contexts:

- Unofficial Sharia Courts in the UK: In Britain, some Muslim communities have established informal Sharia councils to resolve family disputes, particularly around marriage and divorce. While these councils are not legally binding, critics argue that they sometimes pressure women into accepting unequal settlements or discourage them from seeking justice through the secular courts. Investigations have revealed cases where women were denied divorce or advised to remain in abusive marriages under religious guidance.

- Refah Party Case in Europe: The European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2003 that Sharia law was incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights, citing the case of the Turkish Refah Party, which had called for the implementation of Sharia in Turkey. The court noted that such calls, especially when accompanied by threatening rhetoric, posed a risk to democratic order.

- Community Enforcement in Migrant Neighborhoods: In parts of Germany and Sweden, there have been reports of self-appointed “Sharia patrols” where individuals—often young men from refugee or migrant backgrounds—attempted to enforce Islamic norms on dress, alcohol consumption, or public behavior. These patrols, though not sanctioned by any religious authority, created fear and public backlash, prompting police intervention and legal action.

- Blasphemy and Apostasy Pressure: In some Western cities, individuals who leave Islam or publicly criticize religious practices have faced threats or harassment from within their own communities. While these incidents are not representative of all Muslims, they highlight how personal enforcement of religious norms can infringe on others’ rights to freedom of belief and expression.

- Texas: Cleric’s Sharia Campaign Sparks Statewide Ban: In 2025, a Muslim cleric in Houston, Texas, was filmed using a loudspeaker to pressure local shopkeepers—particularly Muslim-owned businesses—to stop selling alcohol, pork, and lottery tickets. He warned that failure to comply with Islamic prohibitions would result in public demonstrations and unspecified action. The incident, widely circulated online, was perceived by many as an attempt to impose Sharia compliance on private commerce. Texas Governor Greg Abbott responded swiftly, condemning the cleric’s actions as harassment and a threat to civil liberty. He announced that Texas had formally banned the enforcement of Sharia law and urged residents to report any attempts to impose religious codes on businesses or individuals. Abbott emphasized that “no business & no individual should fear fools like this,” and signed legislation reinforcing the state’s commitment to secular law. This episode illustrates how individual efforts to enforce religious law—even without formal authority—can provoke strong legal and political reactions. It also underscores the importance of maintaining clear boundaries between personal belief and public governance.

- Washington Teen Strangled Over Refusal of Arranged Marriage: A Clash of Tradition and Law: A deeply troubling case occurred in Lacey, Washington, in October 2023, when a 17-year-old girl was violently attacked by her parents after refusing an arranged marriage. According to court documents and multiple eyewitness accounts, her father, Ihsan Ali, confronted her outside Timberline High School and placed her in a chokehold, causing her to lose consciousness. Her mother, Zahraa Ali, also participated in the assault, grabbing the girl from behind and allegedly attempting to drag her away. The teen had previously reported threats and abuse, including plans by her parents to send her to Iraq to marry an older man against her will. She had sought refuge at her former school, hoping to find safety. Witnesses—including her boyfriend and bystanders—intervened during the attack, and the school was placed on lockdown as authorities responded. Both parents were arrested and charged with attempted murder, kidnapping, and assault. The case sparked widespread outrage and renewed debate over the boundaries of religious and cultural practices in Western societies, especially when they conflict with individual rights and legal protections.

The Broader Picture: Integration vs. Imposition

It’s essential to distinguish between peaceful religious practice and attempts to impose religious law on others. Most refugees seek safety, stability, and dignity—not theocratic governance. However, when individuals attempt to recreate the legal or moral systems of their countries of origin in ways that conflict with Western laws, it can lead to:

-

Legal confusion, especially in family and custody cases

-

Social fragmentation, where parallel norms undermine civic unity

-

Safety concerns, particularly for women, LGBTQ+ individuals, or religious minorities

Western societies must uphold their legal standards while fostering respectful dialogue and integration. This means protecting religious freedom without allowing religious law to override civil law.

Countries with Bans or Severe Restrictions on the Qur’an

The Qur’an, as Islam’s central religious text, is generally protected under religious freedom laws in most countries. However, in a small number of nations—particularly those with authoritarian regimes, ethno-religious tensions, or strict secularism—restrictions have been placed on the Qur’an or Islamic practice more broadly. These restrictions vary from outright bans to indirect suppression through censorship, zoning laws, or refusal to recognize Islam as a legal religion.

Here’s a list of countries where the Qur’an has faced bans or significant restrictions:

- Angola: Reports of mosque demolitions and refusal to recognize Islam as a legal religion

- Slovakia: Legal barriers prevent Islam from being officially registered as a religion

- Myanmar: Severe persecution of Muslims, including Rohingya; Qur’an access restricted in camps

- China: Qur’ans confiscated in Xinjiang; Islamic texts censored under anti-extremism laws

- North Korea: All religious texts, including the Qur’an, are banned under totalitarian control

- Eritrea: Islam not officially banned, but religious texts and gatherings are tightly controlled

- Tajikistan: Qur’an distribution restricted; Islamic education and attire heavily regulated

Note: In some cases, the Qur’an is not explicitly banned, but access is limited through indirect means such as censorship, surveillance, or refusal to register Islamic institutions.

These restrictions are often part of broader efforts to suppress religious pluralism, control ideological influence, or maintain national identity. They do not reflect mainstream global norms, where religious freedom—including the right to read and possess sacred texts—is protected.

What Is Sharia Law?

Sharia law, often invoked in headlines and heated debates, is far more layered than its public image suggests. Rooted in centuries of Islamic jurisprudence, Sharia (meaning “the path” in Arabic) is not a singular legal code but a holistic framework that governs both the spiritual and societal dimensions of life. It draws from four primary sources: the Qur’an, the Hadith (sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad), scholarly consensus (ijma), and analogical reasoning (qiyas). Together, these sources shape a system that addresses everything from personal rituals and ethical conduct to civil contracts, family law, and criminal justice.

For many Muslims, Sharia is not merely a set of rules—it is divine guidance, a sacred architecture for living a life of justice, discipline, and moral clarity. It informs daily practices such as prayer, fasting, and charity, while also offering rulings on marriage, inheritance, business dealings, and disputes. In countries where Sharia is implemented as state law—either fully or partially—it can also prescribe punishments for violations of its legal and moral codes.

Categories of Offenses and Punishments

Sharia criminal law traditionally divides offenses into three main categories, each with distinct types of punishment:

-

Hudud (Fixed Punishments): These are considered crimes against God, with penalties explicitly prescribed in the Qur’an or Hadith. They include theft, adultery, false accusation of adultery, drinking alcohol, and apostasy. Punishments may include:

-

Amputation for theft, provided strict evidentiary standards are met

-

Stoning to death for adultery by married individuals; 100 lashes for unmarried offenders

-

Lashing for alcohol consumption

-

Death penalty for apostasy (leaving Islam), in some interpretations

-

-

Qisas (Retribution): These are crimes against individuals, such as murder or bodily harm. The victim or their family may seek retribution or accept compensation (known as diyya or blood money). For example:

-

In cases of murder, the victim’s family may choose execution of the perpetrator or financial compensation

-

-

Ta’zir (Discretionary Punishments): These cover offenses not specified under Hudud or Qisas and are left to judicial discretion. Punishments can range from fines and imprisonment to public reprimand or exile.

Variability in Application

It’s important to note that the application of Sharia law varies widely across Muslim-majority countries. Some nations, like Saudi Arabia and Iran, enforce Hudud punishments in specific cases, while others—such as Indonesia or Malaysia—apply Sharia primarily in personal matters like marriage and inheritance. In many places, Hudud punishments are rarely enforced due to high evidentiary thresholds or international human rights pressure.

Countries and Regions That Have Banned or Restricted Sharia Law

Several countries and jurisdictions around the world have taken legal or constitutional steps to ban the implementation of Sharia law, particularly in their civil or criminal court systems. These bans are often driven by concerns over national sovereignty, secular governance, and the protection of individual rights. Below is a list of countries and regions where Sharia law has been explicitly banned or significantly restricted:

- Slovakia: Passed legislation preventing Islam from being registered as a state religion, blocking Sharia-based institutions.

- Angola: Islam is not officially recognized; mosque closures and zoning laws have been used to suppress Islamic practice.

- China (Xinjiang): Qur’ans and Islamic texts confiscated; Sharia-based practices banned under anti-extremism laws.

- North Korea: All religious law—including Sharia—is banned under totalitarian control.

- France: While not banned outright, French law prohibits religious law from influencing civil or criminal courts. Sharia tribunals are not recognized.

- Greece (outside Thrace): Sharia law was previously allowed in Thrace for Muslim minorities but has since been restricted to uphold constitutional equality.

- United States (select states): States like Texas, Oklahoma, and Alabama have passed laws banning courts from applying foreign laws, including Sharia.

- India (some proposals): While India allows personal law for religious communities, there have been political efforts to implement a Uniform Civil Code that would override Sharia-based rulings.

- Austria and Hungary: Strong nationalist policies have led to restrictions on Islamic institutions and rejection of Sharia-based legal influence.

Key Motivations Behind These Bans

-

Preserving secular legal systems and constitutional authority

-

Preventing parallel legal structures that could undermine national unity

-

Protecting individual rights, especially for women and religious minorities

-

Responding to public concerns over extremism or cultural integration

These bans are often controversial, with critics arguing they may unfairly target Muslim communities or stifle religious freedom. Supporters, however, view them as necessary safeguards to uphold democratic values and prevent the erosion of civil law.

Countries That Have Refused or Restricted Muslim Refugee Intake

Here’s a list of countries that have either explicitly refused, severely restricted, or shown reluctance to accept Muslim refugees—particularly during major humanitarian crises such as the Syrian civil war or the displacement of Palestinians. These refusals often stem from political, security, sectarian, or cultural concerns.

- Poland: Refused EU quotas for Muslim refugees citing cultural incompatibility and security concerns.

- Hungary: Built border fences and rejected Muslim refugee resettlement, emphasizing Christian identity.

- Slovakia: Accepted only Christian refugees, citing difficulty integrating Muslims into Slovak society.

- Czech Republic: Opposed EU refugee quotas; officials expressed concern over Islamic culture and terrorism risks.

- Japan: Extremely limited refugee intake overall; has not accepted Muslim refugees in significant numbers.

- China: Muslim refugees, especially Uyghurs, face persecution; Islamic practice is heavily suppressed.

- Myanmar: Refused to recognize Rohingya Muslims as citizens; mass displacement and violence documented.

- India: Proposed citizenship laws favoring non-Muslim refugees; Muslim asylum seekers face legal hurdles.

- Israel: Does not accept Muslim refugees from neighboring Arab states; security and demographic concerns.

- Gulf States (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar): Despite wealth and proximity, offered few formal resettlement slots for Syrian refugees.

- Egypt & Jordan (re: Gaza): Recently declared they will not accept Palestinian refugees from Gaza due to fears of permanent displacement.

Context Matters

-

Some countries, like Saudi Arabia, claim to have hosted large numbers of Syrians informally, but without granting refugee status or legal protections.

-

Others, like India or Israel, cite national security and demographic stability as reasons for exclusion.

-

In Europe, resistance often stems from cultural and religious tensions, especially following terror attacks or integration challenges.

Upholding Western Values in the Face of Religious Legalism

In a free society, tolerance must never be confused with submission. The Western tradition—rooted in centuries of struggle for liberty, reason, and individual dignity—demands more than passive acceptance of cultural difference. It requires discernment. It requires moral courage. And above all, it requires unwavering commitment to the principles that define Western civilization: secular governance, equal protection under the law, freedom of conscience, and the inviolable rights of the individual.

Religious freedom is a cornerstone of Western democracy. It guarantees every citizen the right to worship—or not worship—without fear of persecution. But this freedom is not absolute. It does not extend to practices or ideologies that seek to override civil law, suppress dissent, or impose religious doctrine on others. When any belief system—be it religious, political, or cultural—crosses the line from private conviction into public coercion, it must be met with firm resistance.

Sharia law, when practiced privately as a moral or spiritual guide, falls within the bounds of religious liberty. But when individuals or communities attempt to enforce its legal codes—especially those that contradict Western norms of gender equality, freedom of speech, or due process—they challenge the very fabric of democratic society. Whether through informal tribunals, community pressure, or calls for parallel legal systems, such efforts must be critically examined and, where necessary, curtailed.

Western nations must remain vigilant. Vigilant not only against overt threats, but against the slow erosion of civic unity through legal pluralism and moral relativism. Dialogue with Muslim communities is essential—but it must be grounded in mutual respect and shared allegiance to constitutional law. Reform-minded Muslims who seek to reconcile faith with freedom deserve our support. But Western societies must never compromise their foundational values in the name of inclusion.

To preserve liberty, we must be clear: no religious law, no cultural tradition, and no ideological movement may supersede the rule of law. The rights of women, the freedom of conscience, and the equality of all citizens are not negotiable. They are the bedrock of Western civilization—and they must be defended with clarity, conviction, and moral strength.

Credible Sources Referenced

-

Encyclopedia Britannica – Sharia Law Overview Offers a historical and legal analysis of Sharia’s evolution, its application across Muslim-majority countries, and its interaction with Western legal systems. Read the Britannica entry on Sharia Law

-

Springer Academic Publication – Shari’a as Legal Pluralism Explores how Sharia functions informally in Western Muslim communities, highlighting lived experiences and the diversity of interpretations. View the Springer chapter on Shari’a in Western contexts

-

U.S. State-Level Legislation and News Reports Includes coverage of Texas’s ban on Sharia law following incidents involving attempts to impose religious restrictions on businesses. (Referenced from public legislative records and verified news outlets.)

-

European Court of Human Rights – Refah Party Case (2003) Landmark ruling that declared Sharia law incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. (Available via ECHR archives and legal commentary.)

-

Reports from Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International Document practices under Sharia law in countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan, especially regarding corporal punishment, gender inequality, and apostasy laws.

-

Migration Policy Institute & Pew Research Center Provide data on refugee intake policies, religious demographics, and public opinion on Sharia law in Western countries.

-

Verified News Coverage of Specific Incidents

-

The Lacey, WA assault case involving a Muslim father and daughter (covered by regional news outlets and court filings).

-

Sharia patrols in Germany and the UK (reported by BBC, Deutsche Welle, and The Guardian).

-

Texas cleric incident and subsequent legislation (covered by local news and state government releases).

-

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Erin K Stewart