Earliest Christianity (30CE - 100CE): A Socio-Theological Account

An Overview

In order to understand where one presently is and where one is going, it is important to first appreciate where one comes from and has been. From the very beginning, Christianity has been steeped in the theological concepts of the Judaic tradition. This is no surprise as the first Christians were Jewish, as was Jesus Christ himself.

It is important here to recognise that in both the Judaic and Christian traditions, human history is understood as one of salvation. The history of humanity is that of God;s self-revelation to humanity. Although it was taken for granted that Yahweh was the only means of human salvation, the earliest Christians held that His salvific will included all of humankind.

This period of Christian history is of vital importance to the Christian view of non-Christian religions, particularly regarding Judaism. It is the interaction between the early Christians and their surrounding communities which directed the course of thousands of years of Christian inter-religious understanding.

The period bears witness to the development of a new religion out of the fold of the Judaic tradition. As the tension between the new Jesus movement within Judaism and the Orthodox Judaism of the time intensified, we see the Christian movement as adopting Hebraic themes and symbolism and radically adapting them outside of the Jewish tradition. With the understanding of Christ as the sole mediator of God's salvific work, Christians interpreted their tradition as fulfilling and completing that of the Hebrews.

Once outside of the Judaic tradition, Christians were placed into direct conflict with Rome and were subjected to many years of persecution, which negatively influenced the Christian understanding of their relationship with both Jews and pagans.

Common Judaeo-Christian Theological Motifs

The theological intersections between Judaism and Christianity are multitude. However, there are three that are of particular significance for the Christian understanding of both itself and the first century religious world of which it became a distinct part. These are 1) covenant, 2) the Messiah, and 3) the Wisdom of God. Although these scriptural motifs are undeniably Jewish, the earliest Christians took them up and adapted them according to their faith in Jesus as Christ.

1. Covenant

The theology of covenant set the Judaic people apart from the rest of the ancient world. It also led to the development of the understanding that they were a chosen people favoured by God. According to Jewish tradition, the establishment of covenant between God and the Judaic people demonstrates a compassionate enterprise on the part of God. Through this, He freely enters into an intimate relationship with them[1]. In response to such an enterprise, the human party to the covenant is expected to act in constancy and faithfulness according to the boundaries of the relationship. This was seen as being achieved through the mediums of circumcision and sacrifice.

The motif of covenant undergirds the entirety of the Old Testament. It forms the foundation on which the Judaic people developed their faith and culture. This motif is Initiated immediately in the Book of Genesis through the Noahic (Gen 9:1-17)[2] and Abrahamic (Gen 17:1-14)[3] covenants. The Hebrew scriptures continue to trace the covenantal history of the Judaic people through the constitutional covenant with Moses at Mount Sinai (Exod 19-24)[4], and the Davidic covenant established with David in Jerusalem (2 Sam 7)[5].

The New Testament takes up this theme of covenant. It identifies the prophecy of Jeremiah regarding a ‘new covenant’ (Jer 31:31-34) as realised through the paschal mystery of Jesus Christ (Mt 26:28-29; Lk 22:20; 1 Cor 11:25)[6].

2. The Messiah

A fundamental tenet of first-century Judaic tradition and culture was the unyielding presence of messianic hope. Such was an important concept for a community with a history of suffering and upheaval, as was the experience of the Palestinian Judaic people. For the Jews, this was understood according to the divine promises that formed the basis of their self-conception of ‘chosen-ness’. God would be faithful to the covenantal relationship and intervene on their behalf, restoring them and completing His promise of a “kingdom of peace and justice”[7].

The majority of Jews who held this position believed that this restoration was to occur in the future through the actions of a Davidic king who was identified as the Messiah. Such is evidenced most prominently in the Old Testament prophecies of the ‘Suffering Servant’ (Is 53), and those of Micah (Mic 5) and the psalmist (Ps 22).

It is their understanding of the Messiah that set the earliest Christians apart from their more orthodox brethren. For these people, the Messiah was not to be looked forward to as a future development. For them, the messianic prophecies had been realised in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ (Mt 2:1; 27:24-50; Lk 2:4-7; Jn 19:17-30).

3. Wisdom

The concept of the Wisdom (Gk. Sophia) of God was utilised by the Judaic tradition to elucidate the eternal and ever-present manifestation of God in creation. According to the Old Testament, the Wisdom of God belongs only in God Himself (Job 1-11). It was there in the beginning when God created heaven and earth (Prov 8:22-31). It is everywhere throughout God's creation (Sir 24:1-6), though only He knows exactly where (Job 28:1-28). It is understood within the Judaic tradition as having come to dwell in Israel (Bar 3:15-4:1; Sir 24:7-12) and is identified with the covenant between the Israelites and God (Sir 24:23).

The Christian adaption of the Old Testament Wisdom tradition is well known and is most clearly evidenced in the Logos tradition of the Johannine Gospel. It is in this Gospel where Jesus Christ is identified as the Word of God[8]. The significance of this tradition for the Christian understanding of Jesus Christ is manifold. It proved a determining factor for hundreds of years of Christian doctrine regarding his relationship to the Christian community and to the rest of humanity.

[1] Jacques Dupuis, Christianity and the Religions: From Confrontation to Dialogue (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001), 103.

[2] This covenant pertains to the whole of creation, forbidding murder and blessing creation with procreation.

[3] This covenant pertains explicitly to Abraham and his descendents, promising them a great nation in the land of Canaan.

[4] Again, this covenant pertains explicitly to the descendents of Abraham, promising that they will become a priestly nation and instituting the laws of the covenant (Torah).

[5] This covenant establishes David and his descendents as the rightful heirs and rulers of Israel, promising an everlasting Davidic kingdom.

[6] The term ‘paschal mystery’ refers to Jesus’ death on the Cross and his resurrection (Dupuis, Christianity and the Religions, 104).

[7] Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2010), 17.

[8] The Logos tradition of the Fourth Gospel exhibits all the hallmarks of the Wisdom tradition in the Old Testament (mentioned previously). Modern scholarship suggests that it is in fact the Wisdom tradition, though under a different name according to Jesus’ gender; the word Sophia is feminine, whereas Logos is masculine.

The Birth of Christianity

The birth of Christianity as distinct from Judaism was not something which happened overnight, nor in a vacuum. In fact, it took more than 40 years after the death of Jesus for the tension between Judaism and the early Christians to come to a head.

Christianity was initially regarded by the Jewish community as a heretical sect within their tradition which was to be stamped out. The Judaic people had revisited their prophetic texts and considered their loss of independence under Rome to be a result of insufficient faithfulness to their ancestral tradition and covenant with God[1]. They feared that this new faith in Jesus as the Messiah may quite possibly call the wrath of God upon Israel once again. Following the Great Jewish Revolt (66CE) and the subsequent destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple at the hands of the Romans (70CE) however, the Jewish community closed its ranks and Christianity was cast out into a new world.

[1] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 42.

The Apostolic Church

The term ‘apostolic church’ refers to the Christian movement under the authority and guidance of the twelve apostles, the first witnesses who accompanied Jesus on his temporal mission.[1] As Jesus preached the coming of the imminent and universal reign of God, so he charged the apostles with continuing his work after his death and resurrection (Mt 10:5-7).[2] The church was meant to proclaim Jesus’ message to all humankind, but how they understood such a charge, and its consequences for Christianity, demands further discussion.

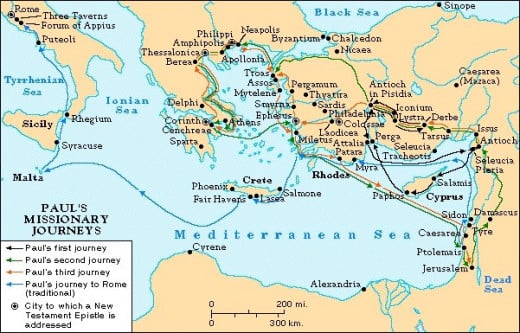

One of the earliest testimonies to the history and theology of the apostolic church regarding those outside of the Jesus community is the Pauline literature. This is regarded as inclusive of the correspondence composed by Saul of Tarsus, known after his conversion experience as Paul. Paul gives evidence to the apostolic church as in a situation of tension between what he understood to be the ‘Torah-free’ gospel and that of the mother church in Jerusalem which was under the authority of James the brother of Jesus.

The apostolic church at the time of Paul was the continuation of decades of exclusively Jewish proclamation, understanding the words of Jesus (Mt 15:24) in a literal sense. However, through his conversion experience, Paul garnered a concept of the proclamation of Jesus’ message as applicable to all humankind, including the Gentile communities[3]. Where the Jewish-Christian community called for full observance of Mosaic Law, including circumcision and laws regarding ritual purity, on the part of Gentile converts (ie. that Gentiles convert to Judaism) in order that they be regarded as Christians, Paul insisted that explicit faith in Christ as the Messiah and Saviour of humanity was enough.

This tension within the broader Christian community culminated in the Jerusalem Council (Gal 2:1-10: Acts 15) (49CE) and a showdown between Paul and Peter at Antioch in Syria (Gal 2:11-14) shortly after, which determined the direction that Christianity was ultimately to take. The Jerusalem Council was convened in an attempt to resolve the very serious problem of circumcision mentioned above, which was dramatically affecting the unity of the early Church. Luke depicts the outcome of the Council of Jerusalem as favouring the Pauline position (cf. Acts 15:11).

The conflict at Antioch as described by Paul himself suggests that Luke's portrayal was not an accurate representation. Following Peter’s arrival in Antioch after the Jerusalem conference, he readily conformed to conventional Antiochene practice (Gal 2:14), including mixed table-fellowship between Jewish and Gentile Christians (Gal 2:12). Upon the arrival in Antioch of a deputation in the name of James however, he withdrew from such table-fellowship out of fear (Gal 2:12). These actions set an example for Barnabus and the rest of the Antiochene Jewish Christian community, which they duly followed (Gal 2:13). It was thus that Paul challenged Peter both privately “to his face” (Gal 2:11), and publicly before the whole Antiochene community (Gal 2:14). He accused Peter of deplorable hypocrisy, with his actions defying and deeply threatening the gospel by which he had previously been living in Antioch. He argued that Peter was effectively forcing the Gentiles into ‘judaising’ if they were not to be denied communion with their Jewish Christian brethren. Although Paul does not explicitly mention the outcome of his confrontation with Peter, it is clear from other information gained from his epistles that he was not the victor in its immediate aftermath.[4]

The Antiochene conflict proved a watershed for the development of the Christian theology of religions. It propelled Paul to widen the scope of his Law-free Gentile mission and ensured that his universal Christian gospel had the opportunity to extend beyond the immediate Diaspora. This Gospel was eventually adopted by the wider apostolic church, and faith in Christ as ultimate for salvation became accessible for all in the first century Gentile world; indeed, by the turn of the century the majority of Christians were Gentile.

[1] Paul posits Peter and John as principal in authority among the apostles, describing them as the “two pillars” (Gal 2:9).

[2] Dupuis, Christianity and the Religions, 25.

[3] The term ‘Gentile’ refers to non-Jewish pagan individuals and communities.

[4] Information such as Paul’s separation from Barnabus’ (Acts 15:39-40), the independence of his subsequent mission (Rom 15:20), and his trouble with the Galatian churches (Craig Hill, Hellenists and Hebrews: Reappraising Division Within the Earliest Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 126-127).

The Johannine Community

The Fourth Gospel pays tribute to the dramatic split between Judaism and Christianity during the apostolic age through the eyes of the Johannine community[1]. This schism engendered a long history of anti-Jewish sentiment within the Christian tradition as a whole.

Written after the destruction of Jerusalem, the Johannine Gospel gives witness to the time of radical restructuring of the Judaic community by the Pharisees following the obliteration of the Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots at the hands of the Romans. As part of this restructuring, the Pharisees endeavoured to establish a new Jewish identity. An element of such was the development of a more stringent and orthodox theology regarding the requirements of the Judaic faith, of which Christianity was still a part. As a result of Paul’s influence on Christian thinking, the apostolic church held an inclusive understanding of admittance into their fold which extended beyond the boundaries of Judaism to include the Gentiles. As the ranks of Judaism tightened, it became clear to the Pharisees that this admittance policy could not be tolerated within the new Judaic identity, and the Johannine Christians were expelled from the synagogues (Jn 9:21; 12:41; 16:2)[2]. Although we do not know how extensive this expulsion was, it is clear from evidence such as this that this period bore witness to the separation of the Jewish and Christian communities on the part of the Judaic tradition itself.

Free from the control of the Judaic tradition, the Johannine community developed radical new understandings of who Jesus and God were, and how they had been/were still operative in human history. The most fundamental of these new developments forms the basis of what was to become the Christian Trinitarian doctrine; that of the Paraclete[3]. According to the Johannine community, the salvific presence of God continued to be present after the departure of Jesus through the universal works of the spirit Paraclete who is present and active in all human communities on the earth (cf. Jn 14:15-17, 25-26; 15:26-27; 16:7-11, 12-15). It is thus that although given the universality of the Gospel of John, it exhibits two main movements within the one Christian tradition; those of pro-Gentile and anti-Jewish.

[1] The community of Christians under the authority of the apostle John.

[2] Francis J. Moloney, “The Gospel of John.” Sacra Pangina 4 (1998): 12.

[3] Moloney, “The Gospel of John,” 21.

Persecution

Once Christianity had moved out of the boundaries of Judaism, its adherents became subject to Roman religious laws which they had not had cause to be concerned about before. Rome had realised that enforcing such laws on the Jewish community more often than not resulted in conflict and rebellion. It was thus that the Jews were allowed a modicum of religious freedom, free to practice their own religion under the banner of the Roman Empire.[1] As a part of Judaism, Christians were also exempted from the rule but following the schism of the two, it became clear that those who followed the Christian tradition were to be treated in religious terms like the rest of the Empire.

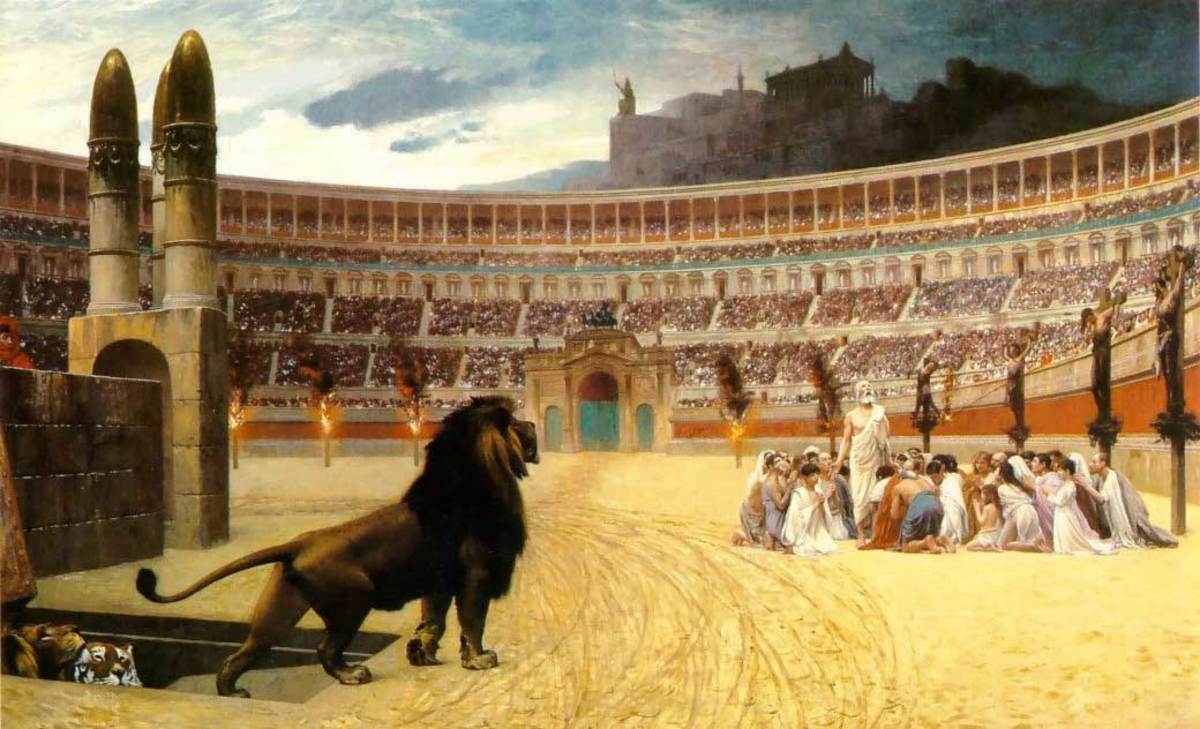

In an attempt to create unity among the many conquered nations of the Roman Empire, Rome embarked on two methods of establishing religious uniformity: syncretism and the imperial cult[2]. These brought the Christians into direct conflict with the Empire, and engendered two and a half centuries of violent persecution.

Syncretism involved the adoption of many gods from the different conquered lands into the Roman pantheon. This was important for the Empire as it gave the illusion that the Roman gods were the one and same gods worshipped in these lands, though under different names. Christians objected to such a practice on the same grounds as did the Jews, namely the insistence on strict monotheism, and their belief in the one mediator of salvation further bolstered their opposition.

The imperial cult revolved around the practice of emperor worship; the identification of the Emperor with the divinely ordained authority of the Roman State. As was the case with the official deities of the State, sacrifice as worship to the Emperor was a vital element in maintain the peace and abundance of the Empire due to the perceived salvific qualities of the Emperor. To refuse to worship considered an act of treason. Unsurprisingly, the Christians objected to such a practice as heresy as the imperial cult placed the Emperor in direct competition with Christ. Furthermore, they denounced the sacrificial system as a mockery of true worship, as they held that the final sacrifice had already been offered through the passion of Christ.

It is in this context that one of the darkest periods of Christian history began under the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero (54-68CE), which was to continue until the reign of Constantine I (306-337CE). Although the Neronian persecution was initiated as a result of the Great Fire of Rome (64CE), it was not long before the focus became purely religious and Christians were targeted solely on the grounds of their faith[3]. The horrors of this period are well documented in the words of late first- and early second-century historians such as Josephus, including the account of the live immolation of numerous Christians to illuminate imperial garden parties[4].

Upon the death of Nero, this exceedingly cruel treatment of Christians was continued at the hands of his successor Domitian (81-96CE). Domitian denounced Christianity as an atheist movement and embarked upon a systematic persecution throughout Asia Minor, which resulted in many deaths. It is from this period that we receive the Book of Revelation, which perhaps gives witness to a revolution in Christian policy towards both Roman authority and the pagans who dwelled within the boundaries of the Roman Empire. Where Paul insisted on obedience to Roman leaders as he believed that they had been ordained by God, John of Patmos speaks of the corruption of the Empire and its divine replacement with the “new Jerusalem” (Rev 21:2).

[1] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 43.

[2] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 20.

[3] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 46.

[4] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 46.