A brief history of Buddhism

Throughout history, tragic events have sparked an increasing interest in religion. There is a direct correlation between massive injury, illness, and high death tolls with an urgent need to seek out a higher power—in order to comfort the soul and provide a sense of security, in an otherwise chaotic world. In a very simple sense, people are on a journey to discover the meaning and purpose of life. Buddhism is an interesting and peaceful religion that offers philosophies on how to attain an understanding of life and the universe.

Buddhism began about 2500 years ago (Fouberg, Murphy, and de Blij 212). Legend has it that when Prince Siddhartha Gautama was born, in the sixth century B.C.E., an old sage foretold that the prince would become an ascetic or a supreme monarch. In order to ensure that he became the future leader and a great warrior, the King decided to isolate Prince Gautama within the confines of the palace, living a life of ultimate luxury. The Prince married and had a son. At 29, he finally made it out of the palace and discovered aging, illness, and death for the very first time. On his journey, he met a homeless man, who smiled at him with a sense of contentment and peace. Confused, he asked how this man, with so very little, could find happiness in such a miserable world. He was told that the homeless man had met with a holy man, someone who had achieved complete liberation. This trip was shocking and dramatically changed the Prince’s outlook. He renounced his luxurious lifestyle, believing it to be an empty existence. He embarked on a spiritual quest, determined to find a solution to human suffering (Toropov and Buckles 200). After years of living ascetically and intense studying, Gautama came to sit under a Bodhi tree, vowing to stay there and meditate until becoming fully liberated. “On the morning of the seventh day, he opened his eyes and looked out to the morning star. At that moment, he became enlightened” (Toropov and Buckles 201). From this moment, Gautama became known as the Buddha, which means enlightened one (Fouberg, Murphy, and de Blij 213); today he is known as Buddha Tathagata , which means “he who has gone through completely” (Toropov and Buckles 200); in China, and some parts of the Eastern world, is referred to as Buddha Shakyamuni (Kung 4).

Five of the Buddha’s companions met with him in the Deer Park, in Varanasi, a city in Northeastern India on the Ganges. Here, under the Bodhi tree, the Buddha delivered his speech on the Four Noble Truths, “There is suffering. There is the origin of suffering. There is the cessation of suffering. There is the path out of suffering” (Sumedho 8). These Truths, along with the Eightfold Path, comprise the basic doctrines of Buddhism. “A Noble Truth is a truth to reflect upon; it is not an absolute; it is not the Absolute” (Sumedho 13).

The First Noble Truth, ‘There is suffering,’ is a basic insight, requiring only recognition. It’s important to remove any personal feelings and attachments to this insight; The suffering is not ‘mine,’ but rather the insight is made as a reflection, “there is this suffering, this dukkha (suffering). It is coming from the reflective position of Buddha seeing the Dhamma (truth)” (Sumedho 9). Human existence is inherently painful and this dukkha is the common bond that unites all human beings. It is also important to note that a first step in accepting and admitting that ‘there is suffering,’ is to let go of the psychological ego. “Admission in Buddhist meditation is not from a position of: ‘I am suffering’ but rather, ‘There is the presence of suffering’ because we are not trying to identify with the problem but simply acknowledge that there is one” (Sumedho 15). The Buddha said, “What is the Noble Truth of Suffering? Birth is suffering, aging is suffering, sickness is suffering, dissociation from the loved is suffering: in short the five categories affected by clinging are suffering” (Samyutta Nikaya LVI, 11)

Within the Second Noble Truth, ‘There is origin of suffering,’ the Buddha taught that suffering arises from three types of desire, craving, and attachment. The three types of desire include: the desire for sensual pleasure, the desire to become, and desire to get rid of. In a very simple sense, suffering originates from attachment to desire—grasping at desire (Sumedho 27-30). Again, the Truth is a reflection, requiring the acknowledgement of desire, rather than identifying with it. The Buddha said, “What is the Noble Truth of the Origin of Suffering? It is craving which renews being and is accompanied by relish and lust, relishing this and that: In other words, craving for sensual desires, craving for being, craving for non-being. But whereon does this craving arise and flourish? Wherever there is what seems lovable and gratifying, thereon it arises and flourishes” (Samyutta Nikaya LVI, 11).

The Third Noble Truth is ‘There is cessation of suffering.’ “The whole aim of Buddhist teaching is to develop the reflective mind in order to let go of the delusions” (Sumedho 36). It’s about contemplating versus forming opinions, reflections versus belief. This mental state is vital to eliminating suffering. A principle of the Dhamma that the Buddha stressed was: “Each thing arises from a cause. We must know the cause of that thing and the ceasing of the cause of that thing” (Bhikkhu 4). In a very simple sense, once a person has transcended craving and attachment, he or she enters the state of Nirvana, and suffering ceases (Toropov and Buckles 203). The Buddha said, “What is the Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering? It is the remainderless fading and cessation of that same craving; the rejecting, relinquishing, leaving, and renouncing of it. But whereon is this craving abandoned and made to cease? Wherever there is what seems lovable and gratifying, thereon it is abandoned and made to cease” (Samyutta Nikaya LVI, 11).

The Fourth Noble Truth, ‘There is the path out of suffering’ teaches the Eightfold Path. The elements are grouped together in a sequence with three sections:

1. Wisdom – Right Understanding; Right Aspiration

Reflecting on the previous three insights and accepting things for how they are; “When there is Right Understanding, we aspire for truth, beauty, and goodness” (Sumedho 54-55)

2. Morality – Right Speech; Right Action; Right Livelihood

“Taking responsibility for our speech and being careful about what we do with our bodies” (Sumedho 57).

3. Concentration – Right Effort; Right Mindfulness; Right Concentration

These three elements refer to the spirit and the heart, free from selfishness. “When the heart is pure, the mind is peaceful... Reflectiveness of mind or emotional balance is developed as a result of practicing concentration and mindfulness meditation” (Sumedho 48, 60).

The Buddha taught that this is the path one must take to reach Nirvana: the state of final liberation from the cycle of birth and death. “This immortal element is the cessation of the mortal element” (Bhikkhu 36). It is worth noting that The Four Noble Truths are an original set of founding ideas that have never been used as a justification for acts of violence, war, or military exploit.

In addition to the above Truths, the Buddha taught several other principles: Walking the Middle Way, striking a balance to create optimal conditions for studying and practice, and success in eliminating suffering; Self-help, not relying on fortunes and fame, God, or celestial beings, each person making their own effort – self is the refuge of self; Avoid evil, do good, purify the mind; and nothing is permanent, “All compounded things are perpetually flowing, forever breaking up. Let all be well-equipped with heedfulness” (Bhikkhu 5). Moreover, Buddha taught that “to believe straight away is foolishness; to believe after having seen clearly is good sense” (Bhikkhu 19). One must not whole-heartedly accept what information is offered, without first fully contemplating, considering, examining, and analyzing the information for oneself. Anyone has the ability to seek out understanding, follow the Eightfold Path, and achieve enlightenment. The Buddha continued teaching until his death at age 80. His final words say it best, “All composite things decay. Diligently work out your salvation” (Toropov and Buckles 206).

The Diffusion of Buddhism

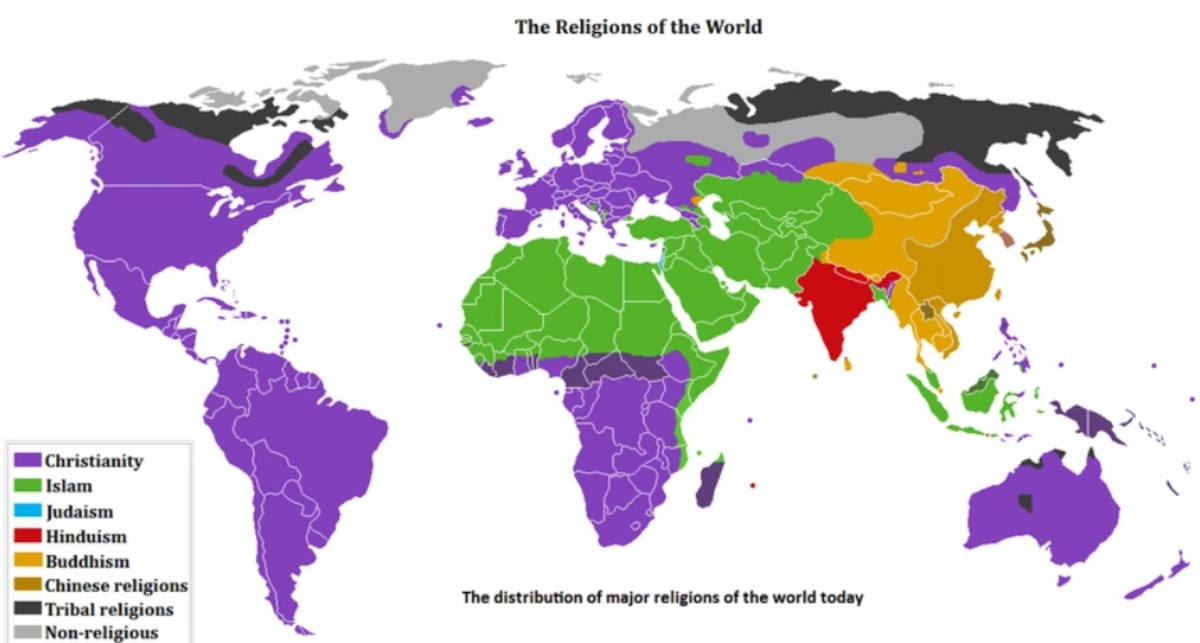

The hearth of Buddhism lies in Northeastern India, in the city on the Ganges River, where the Buddha achieved enlightenment, and delivered his first lecture on the Dhamma. For the next 45 years, he and his followers traveled through the North Indian River Plains, Eastern India, parts of modern day Pakistan, Southern Nepal, and areas of Bangladesh “teaching, ordaining monks, and promoting the solitary, secluded style of spiritual discipline” (Toropov and Buckles 205). After his death, the new religion grew slowly. The Buddha had not named a formal successor and three months after his death, a first council was convened at Rajagrha, to uphold the Buddha’s final wishes: not to follow a leader, but to follow the teachings and spread the Buddhist wisdom. One hundred years later, a second council was convened at Vaishali to settle growing disputes about the teachings.

In the third century B.C.E., Emperor Asoka, leader of the large and powerful Maurya Empire, converted to Buddhism. He ruled his empire in accordance with the Buddhist teachings and sent missionaries to distant lands to spread the teachings (Fouberg, Murphy, and de Blij 213). A third council was convened by the emperor and led by a monk, Mahakasyapa, to settle growing differences among followers and determine a direction for the faith. As a result, 18 schools of Buddhism emerged and were acknowledged. Of these 18, only the Theravada school exists today (Toropov and Buckles 208). The Theravada school considers the Buddha’s teachings to be the most sacred and emphasizes the solitary life of personal religious discipline. Around 100 B.C.E., a contrasting view of Buddhism, Mahayana, was presented from Nagarjuna, a revered philosopher. One of his most important principles was that Nirvana is a reality that can exist in the present moment (Toropov and Buckles 209-211).

Buddhism continued to spread through Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, and China via trade and sea routes. During the second century B.C.E., sculptures of the Buddha’s life and teachings appeared and in the first century C.E., Buddhist art took on anthropomorphic representations. Chinese monks brought Buddhism to Korea around 372 C.E. From Korea, Buddhism spread to Japan, where it became the official state religion in the eighth century C.E. Buddhism also diffused into Tibet, Laos, Cambodia, Taiwan, and Thailand.

Buddhism didn’t reach the West until the 18th century. As people traveled to colonies in the East, they encountered these new philosophies and brought back Buddhist texts. European scholars began to study them and in the 19th century, these texts were translated into a few European languages. This allowed for more people to study them and write out their own reflections on the topics. By the 20th century, the entire Theravada scriptures and the important Mahayana texts had been translated in English, French, and German. In 1924, The Buddhist Society was established in London, helping to grow interest in Buddhism through meditative sessions, lectures, and circulating the Buddhist literature (BuddhaNet). Chinese and Japanese immigrants helped spread Buddhism through North America. At the end of the 19th Century, two revered Buddhist spokesmen attended the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Dharmapala, from Sri Lanka, and Soyen Shaku, a Zen Master from Japan, gave inspiring lectures that impressed their audience. They helped to establish interest in Theravada and Zen Buddhism in the United States (BuddhaNet). After WWII, interest in Buddhism in the United States grew. Tibetan refugees brought Vajrayana Buddhist traditions to America and, during the 60’s, Zen Buddhism traditions became popular. Today, a number of Buddhist centers and societies exist across Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and North and South America.

Credits

Behl, Benoy K. "The Great Buddhist Diffusion." Buddhist Channel. The Buddhist Channel, 17 Dec. 2008. Web. 01 Dec. 2012.

<http://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=5,7531,0,0,1,0>.

Bhikkhu, Buddhadasa. "Buddha Dhamma for University Students." (n.d.): n. pag. Buddhanet. Web. 2 Nov. 2012.

<http://www.buddhistelibrary.org/en/displayimage.php?pid=67>.

"Buddhism Timeline." Timeline of Buddhism. Religion Facts, 17 Mar. 2004. Web. 01 Dec. 2012. <http://www.religionfacts.com/buddhism/timeline.htm>.

"The Buddhist World: Spread of Buddhism to the West." The Buddhist World: Spread of Buddhism to the West. BuddhaNet, 2008. Web. 01 Dec. 2012.

<http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/to-west.htm>.

Fouberg, Erin H., Alexander B. Murphy, and H.J. De Blij. Human Geography People, Place, Culture. 10th ed. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons, 2012. Print.

Kung, Chin. "The Art of Living Part 1 and 2." (n.d.): n. pag. Buddhanet. Web. 2 Nov. 2012. <http://www.buddhistelibrary.org/en/displayimage.php?pid=69>.

Kung, Chin. "Buddhism as an Education." (n.d.): n. pag. Buddhanet. Web. 2 Nov. 2012. <http://www.buddhistelibrary.org/en/displayimage.php?pid=71>.

Sumedo, Ajahn. "The Four Noble Truths." (n.d.): n. pag. Buddhanet. Web. 2 Nov. 2012. <http://www.buddhistelibrary.org/en/displayimage.php?pid=43http://>.

Toropov, Brandon, and Luke Buckles. The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Religions. 3rd ed. New York: Beach Brook Productions, 2004. Print.