Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation

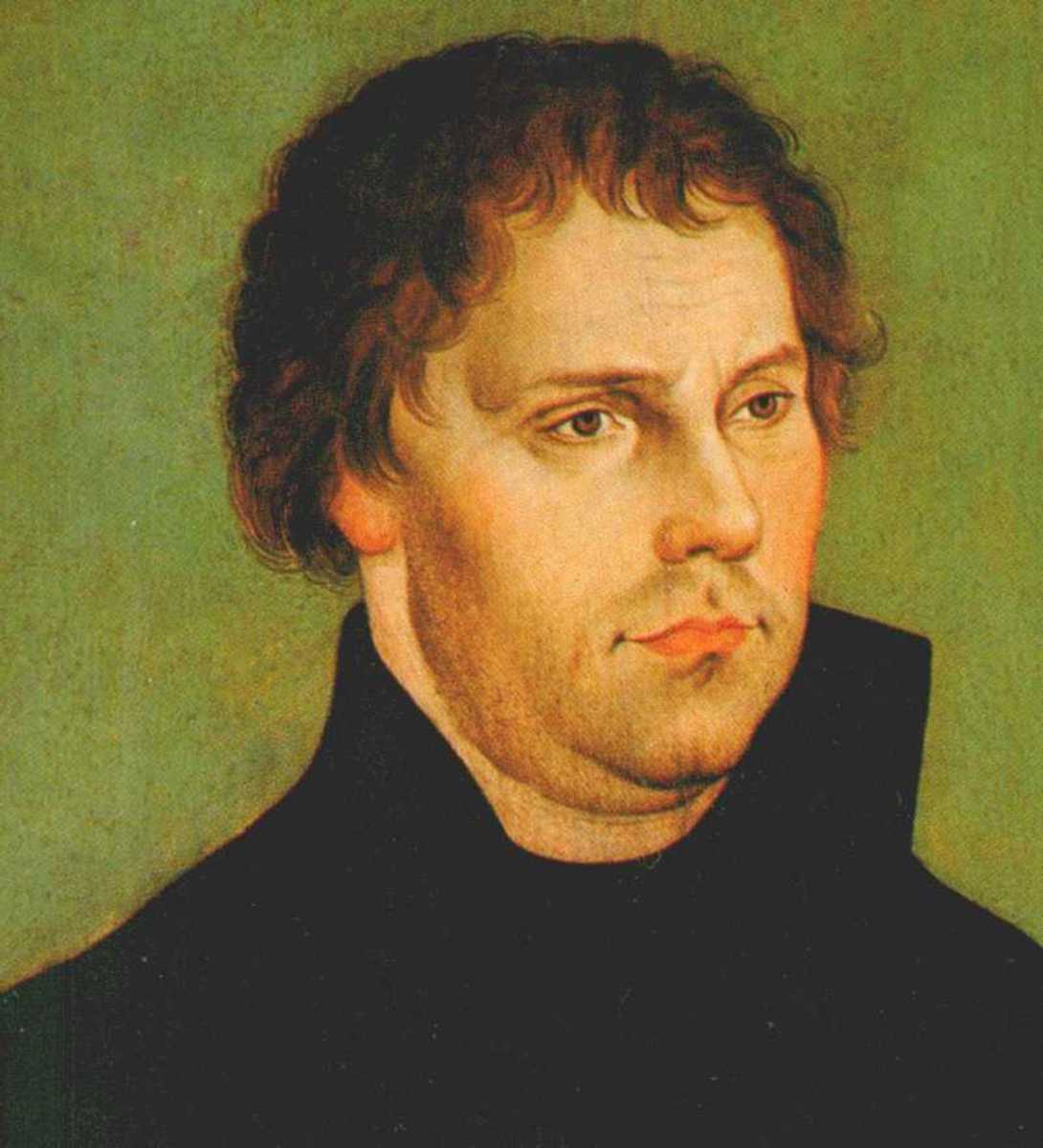

In the center of the religious, political and social revolution that broke the hold of the Catholic Church over Europe, one finds the founder of the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther (1483-1546) (Mullet, par. 1).

Luther, born in Eisleben in Eastern Germany, (Mullet, par. 1) was ordained priest in 1507 (Mullet, par. 3) in spite of his father’s wishes to train for the legal profession (Mullet, par. 2).

Luther’s life was haunted by the fear of God’s judgment and spent his life seeking everlasting salvation (Mullet, par. 2); however, Luther gradually found assurance in the scriptures: “the Psalms of the Old Testament and the Epistle of St Paul to the Romans in the New” Testament (Mullet, par 4). Consequently, Martin Luther, with a courageous and bold act, brought about one of history’s symbolic moment known as the Protestant Reformation.

Contrary to the Catholic Church’s teachings, Luther argued that sinners won acceptance, not by good deeds (Mullet, Par. 4) and not by the "practicing of rituals or doing pious works” (Boggis, p. 3), such as the selling of indulgences, but simply by faith that Christ had died on the cross (Mullet, Par. 4) to atone for their sins (Mullett, par. 22).

On October 31, 1517, in protest against the sales of indulgences in Germany, by Friar Johann Tetzel, Martin Luther challenged the papacy with 95 Theses and nailed the theses to the door of "the CastleChurch in Wittenberg, in the German principality of Saxony- and thereby precipitated the Reformation” (Mullet, Par.7).

The unsuspecting Luther, who only urged moderation in the indulgences, marked the beginnings of a major "future change of rites” (Mullett, par. 9). This sole act was not significant or unusual, since universities are known for their posters advertising forthcoming events on the door of the Castle Church and theologians convened and debated legitimacy of religious issues (Mullett, par. 15); it was the publicity that turned this act into a world-shattering event by the printing of the manifesto that sensationalized and precipitated the change and rebellion in a country filled with a mix “of religious, moral, political, and financial grievances against the Roman Church” (Mullett, par. 16).

In 1520, according to Gritsch, Luther was threatened by Rome, and was to be excommunicated if he did not recant his teachings, however, Luther refused to do so (Gritsch, par. 4). In 1521, following the challenge to the papacy’s “claimed divinely-endowed power to pardon,” (Mullet, Par. 5), “under pressure from Elector Frederick and other princes, Emperor Charles V agreed to hear Luther at a German diet scheduled to meet in Worms” (Gritsch, par. 4). Meanwhile, virtually all of Germany was supporting Luther (Gritsch, par. 5). Luther appeared before the diet, where he was asked, “did he acknowledge the authorship of books that had been brought to the diet and bore his name?” and “Would he stand by them or retract anything in them?” (Gritsch, par. 6). According to Gritsch, at Luther’s request, he was allowed to meditate for a day to reflect before answering, nonetheless, Luther refused, maintaining his ground, and was asked to leave Worms (Gritsch, par 7, 10).

On May 26, 1521, Charles excommunicated Luther and declared him a criminal, demanded the capture of Luther and his disciples, and condemned him to death; however, according to Gritsch, an arranged kidnapping by his supporter, Elector Frederick, Luther was hidden at Wartburg, thus saving his life (Gritsch, par. 9, 10).

According to Mullet and Gritsch, the search for everlasting salvation through personal reflection and lectures of the scriptures, led Martin Luther to challenge the Catholic Church’s selling of indulgences, and argued that sinners were forgiven for their sins, not by good deeds and rituals, but simply by faith. By nailing the 95 Theses to the CastleChurch’s door, and the events that followed at the Diet of Worms, Luther spurred a historical movement that lead to the Protestant Reformation.

Citation:

Boggis, Jay. The Western Tradition- Third Edition. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 2001.

Gritsch, Eric W. “The Diet of Worms.” Christian History 1990: 36. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 1 March 2005 <http://search.epnet.com>

Mullett, Michael. “Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses.” History Review September 2003: 46-51. EBSCO. 24 February 2005 <http://search.epnet.com>

©Faithful Daughter