A Church in Flux: The Shifting Ethos, Doctrines, and Organization of Christianity Between the First and Fourth Centuries

It is not difficult to enumerate ways in which Christianity changed over its early history. A challenge will be found, however, in the fact that these changes were so extensive that it is impossible to discuss them all in a short essay. At any rate, during the period between the death of Jesus and the late fourth century, the early church underwent vast changes in its attitudes, beliefs, structure, and social position.

Changes in attitudes and beliefs could be seen, for example, in Christianity's stance towards Jewish law. Of course, Jesus himself was Jewish, as were his earliest followers. The Jesus movement understood itself as Jewish from the very beginning (Ehrman, After NT 95). Thus, the earliest followers of Christ continued to follow the commandments of the Torah, as can be seen in Matthew 5:19, where Jesus is quoted as saying that whoever breaks “the least [emphasis added]of these commandments . . . will be called least in the kingdom.” Taken at face value, this injunction by Jesus would imply that his followers were to keep even kashrut laws and the law of circumcision. Eventually, however, other views were to prevail. A good example of these views is provided by Paul's letter to the Galatians, in which adherence to the Jewish law of circumcision was not only depicted as useless, but was said to render “Christ . . . of no benefit” (Gal. 5:2) to the Galatians. Likewise, The Epistle of Barnabas, by means of allegorical interpretation, does away with the literal observance of kashrut laws (Chapter 10).

Eventually, this new attitude towards Torah law would spill over into hostilities towards the “Jews” themselves. I put “Jews” in quotations to emphasize the retrospective nature of this Christian label of Jesus's Jewish detractors, which ignored the fact that his early supporters were also Jewish (Shepardson 01/26/12). This change in attitudes toward Jews and Jewish law paralleled the Jesus movement's transition from being an apocalyptic Jewish sect to a universal movement which aimed to draw in “Gentile” converts throughout the Hellenistic Roman Empire (Ehrman/Jacobs 2-3).

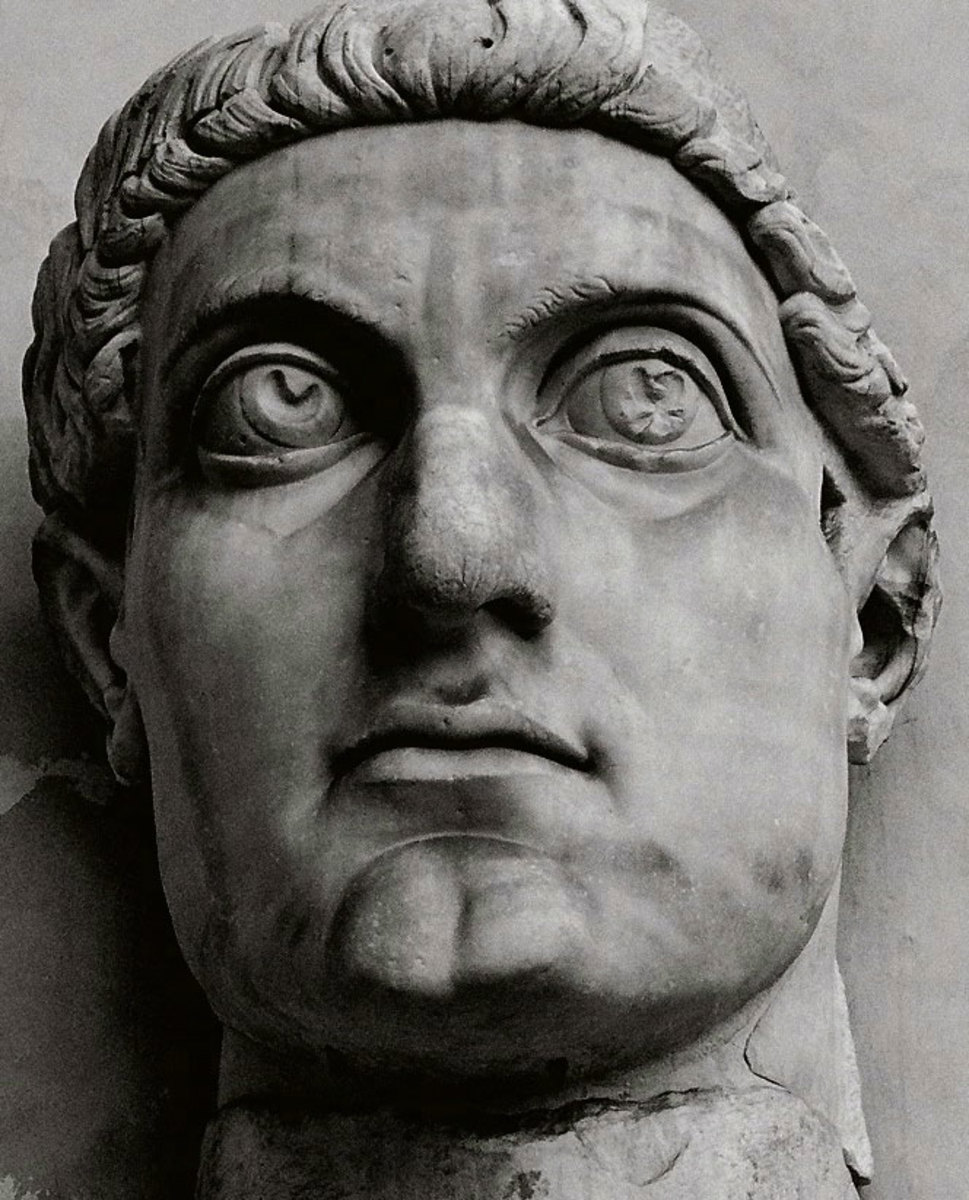

Christian attitudes towards women also changed dramatically during the first century of its history. Christian writings dated to the middle of the first century depict egalitarian gender attitudes, naming women among the “prominent . . . apostles” (Rom. 16:6), and even overlooking gender distinctions altogether (Gal 3:28). By the end of the first century, however, the proto-orthodox strain of Christianity was becoming male-dominated, as evidenced by their language of female “submission” (1 Tim 2:11) and “obedience” (1 Clement 1:3). It is likely that the earliest Christian gender conceptions were considerably more progressive than those of the surrounding culture. Paul's naming of women as prominent apostles within the Christian ἐκκλησία (Ekklesia) would have given women a position of authority and importance never found, for example, in the ἐκκλησία of Athenian democracy, which included only males—granted, Athenian democracy ended before Christianity ever came on the scene, but the Roman empire was likewise male-dominated. Thus the increasingly male-dominated gender attitudes of Christianity may have partially reflected a movement towards assimilation within its sociocultural milieu (Shepardson 01/26/12). Christianity would continue to assimilate into the surrounding culture, and after the conversion of Constantine would begin to overlap “directly with the political concerns of Roman emperors” (Ehrman/Jacobs 4).

One factor contributing to early Christianity's increasing enmeshment with surrounding social and political structures was that the apocalyptic fervor of earliest Christianity—apparent, for example, in Mark 8:38 – 9:1, where Jesus is talking about his return, and then seems to suggest that this would occur during the lifetimes of some members of his audience—dwindled over the years, as the apocalypse failed to materialize (Shepardson 01/26/12). These two developments helped to fuel the increasing institutionalization of the Christian church. Although in Matthew 23:8-11, Jesus is depicted as proscribing the use of honorary titles, such as “father” or “teacher”, the institutionalization of Christianity was effected largely through the establishment of titles and offices (Ehrman/Jacobs 129), such as “επίσκοπος” (“bishop”, literally “overseer”). Amazingly, as much as the nascent movement railed against the religion from whence it originated, it in certain ways almost modeled itself after the hierarchical Levitical system, going so far as to call the επίσκοπος “the high priest” (Hippolytus, Apostolic Tradition, Chapter 30).

Along with the proliferation of clerical titles and offices came a drive towards greater uniformity, both in doctrine and praxis. Attempts at ritual uniformity played a role in proto-orthodox Christianity's process of self-definition. For example, the Didache delineates a boundary between one sort of ingroup and outgroup by saying, “[The hypocrites] fast on Mondays and Thursdays; but you should fast on Wednesdays and Fridays” (Didache 8:1). Doctrinal uniformity came to have even greater importance for separating the true believers from the “heretics”. While second and third century Christian beliefs were extremely diverse, with a number of different “Christianities” (Ehrman, New Testament 1) thriving in an uneasy “state of plurality” (Ehrman/Jacobs 155), by the late fourth century, the proto-orthodox Christians wielded such influence within the Roman political system that writings of contradictory Christianities were proscribed (Ehrman, After NT 132), as were many “traditional Roman religious practices” (Ehrman/Jacobs 4). It is a great tragedy that the long process of canon formation culminated in the annihilation of a vast body of religious literature that was at odds with the literature of the proto-orthodox Christians (Ehrman, After NT 194). This seems an incalculable loss to scholarship and to humanity overall.

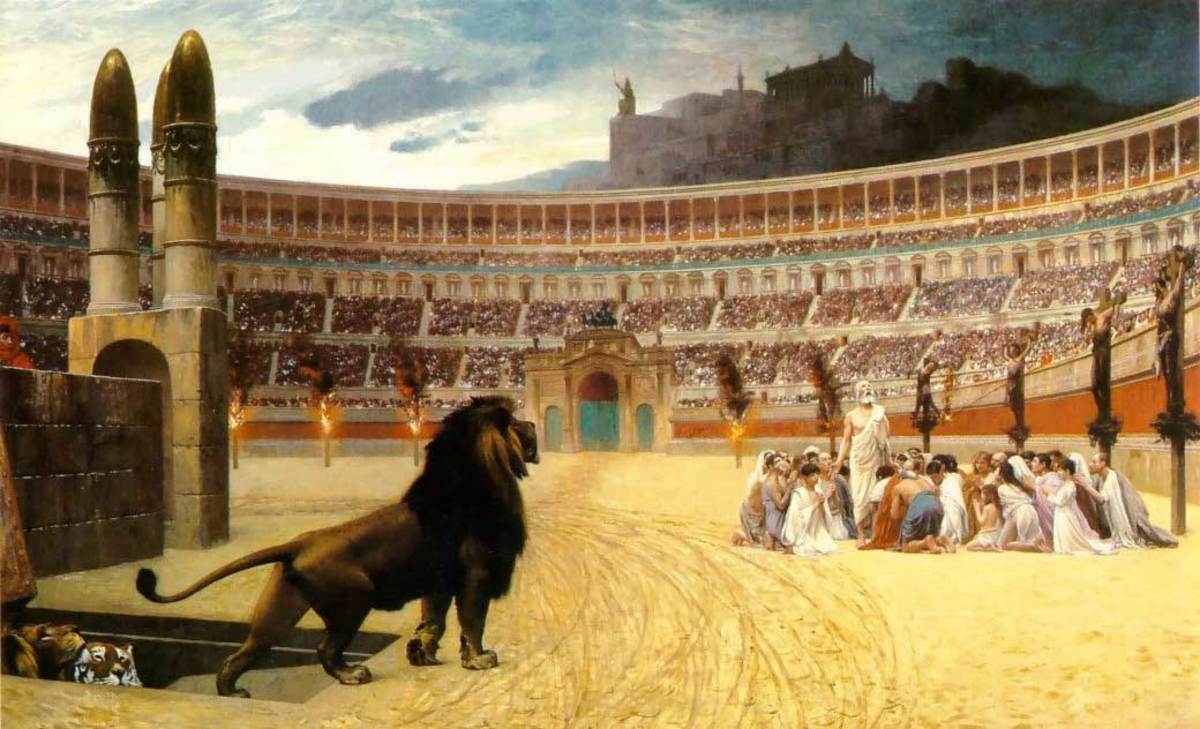

So by the end of the fourth century, the social position of the Christian church was the opposite of what it had been in the first through third centuries. Once a scorned minority, “lashing out” (Ehrman, New Testament 423) against larger opponents, such as non-Christian Jews, they had become the “high and mighty” (Ehrman, New Testament 423), and joining them was fashionable and even advisable (Ehrman, New Testament 424).

So from its attitudes and beliefs about Jewish law, to its increasingly institutionalized structure, to the 180 degree turn-around in its social position, Christianity underwent many drastic changes indeed between the mid-first and late fourth centuries.