God And The New Haven Railway

"The desire that drives true religion should be so central to the dignity of humanity that jettisoning God is tantamount to abandoning the central theme of the human story"

The trouble with life

This world is a pain. Things don't go right, and human beings simply don't have the answers. This is why religion exists. In God And The New Haven Railway, And Why Neither One Is Doing Very Well, Dennis O'Brien uses a decrepit public transportation system as both an illustration and a metaphor for the human condition.

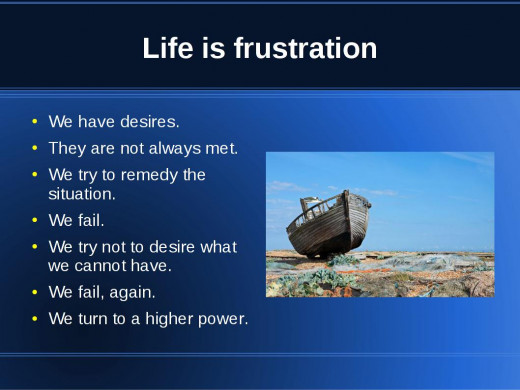

O'Brien's thesis is that there is no escaping the need for some sort of God. This book goes through all the various strategies of getting by without religion, and shows why they just don't work in the long run. His analysis of the problem of human suffering is not unlike Buddhism, but he rejects the Buddhist solution as unworkable. It is fundamental to human nature to want things to be other than they tend to be. We want to get to work on time, but the train doesn't run. We want to live forever, but we die. The human soul refuses to accept frustration and limits. This is why we reach out for God. But which God?

A catalog of coping strategies

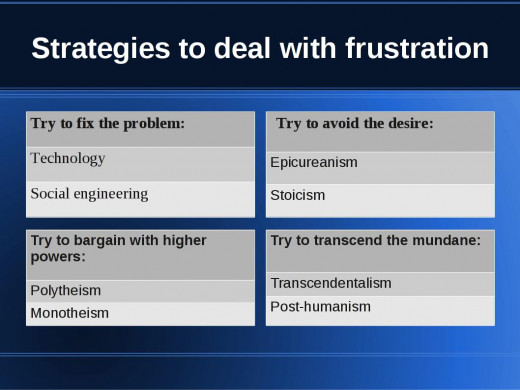

O'Brien goes through all the major religious and philosophical approaches the problem of life one by one, and shows how each fails to satsify. Then, in the second half of the book, he descibes an interpretation of Christianity that is at odds with all the alternatives, but which he argues can actually work.

First, he discusses Stoics and Epicureans: people who try to reduce frustration by making peace with things not being as we would like. The Stoics simply try to accept things as they are, and the Epicureans try to focus on what little they cna control. On the surface, this seems eminently reasonable -- so long as you ignore the realities of human nature. Stoicism just isn't actionable: we can't repress our desires and still be human. Epicureanism is self-defeating: retreating from an unmanageable world won't make it go away. Besides, when you discover that your own soul is beyond repair, there's nowhere left ot retreat to. Religion is necessary when we are no longer able to bargain away desires.

Next, he deals with polytheism. Polytheism sees Heaven as a kind of celestial Mafia, to be bought off. He also describes the cult of fame as a secular polytheism. Polytheisms are unstable. They eventually evolve in monotheisms. But there are two types of monotheisms: a personal God and an impersonal God.

Nature worship is the impersonal God. O'Brien asserts that this is unsatisfactory because there is no bargaining with such a deity, and also because nature is cruel. You can be in awe of Nature, but you cannot worship Nature in the sense that you cna worship a personal God. Nature simply doesn't recognize your existence.

He also dismisses the technologists -- people who think they can fix all problems by conquering Nature. It is unrealistic to think that science and technology can fix everything. Nature is too capricious and powerful. The proof? The New Haven train.

Then there are the transcendentalists -- who reject the world and try to live on a higher plane somehow. O'Brien sees these as similar in spirit to the Epicureans: the Transcendentalists retreat from the outside world and focus on their own selves, to try to become better than they are, to become less worldly. O'Brien rejects this as impractical, given the human desire to relate to the divine, and the necessity of living in this world and with ourselves. It is merely a variant of the impersonal god, combined with a denial of our own nature that's as futile as to deny external Nature.

This puts me in mind of Nietzsche's solution: give up on mankind, and hope for something better to come along. The temptation is strong, but that's not a lot of help to those of us who aren't Supermen. Zarathustra distracted himself from the pain of being human by rejoicing that the Superman would come -- a very transcendentalist attitude. Nietzsche, on the other hand, went insane. He tried to feel as Zarathustra did, but failed. He was human, all too human. He could no more stop caring about the human condition than a horse could sing.

Besides, there's no good reason to believe that a posthuman being won't face the same problems with Nature as we do. The Superman would more likely turn out to be just another limited, frustrated creature.

"It is this ability to take free and responsible action that is the base for human dignity"

The trouble with freedom

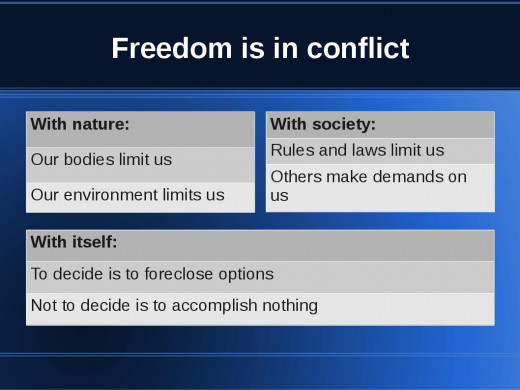

He moves on to discuss human freedom and its difficulties. Human free will is an essential fact and an essential problem. Freedom is at odds with nature, with society and with itself. Nature curses us with a limited, imperfect body that limits our actions. Society puts all sorts of restrictions on us and refuses to accept our freedom to choose, making slaves of us all.

But the biggest irony is that freedom means nothing and accomplishes nothing unless we decide on a course of action or way of being, and to decide is to foreclose all other options, which ends freedom. "Freedom is not the settling kind." He uses the illustration of the Western movie, where the protagonists are always riding off into the sunset, with no clear destination. He compares and contrasts this to the story of the Exodus, in which there was a destination that could not be reached except by submitting to self-discipline. "The problem is arriving."

It is by making decisions and committing to things that we grow and develop character. O'Brien suggests that the proper use of freedom is to decide for ourselves, to define ourselves, and there's no need to mourn its loss after it has accomplished its purpose. But there is one real sin in his view: despair. Faith is the opposite of despair, and is the better choice.

God, revisited

All this is a warm up to the Christian God, but that God seen in a new light. O'Brien argues that what we need is a God who cares enough about us that we can talk with Him, intimately in prayer, and that will lower Himself to get involved in our messy world. We are forced to live in this world, and at the same time we yearn for God. The Judeo-Christian God solves the dilemma. This version of monotheism is life-affirming despite it all. It is God having faith in us.

But hasn't this God been tried and found lacking? Judeo-Christian religion in the United States is as decrepit as commuter rail, because it has been neglected. Commuter rail was neglected because it wasn't meeting peoples' needs, and it got worse at meeting peoples' needs as it got neglected, in a vicious spiral. O'Brien admits that the same thing has happened with religion. His answer: try God again, but this time try to understand God better and to approach Him on His own terms. What are His terms? Faith, for starters. Well, we've tried that. But there's more. He's already talked about action and decision. Now, in the last chapters, he provides the missing piece, and it's no wonder we've missed it: love for this defective, frustrating world.

Not love in an airy-fairy sense, but practical love. We must love the world despite its faults. We must love each other despite each others' faults. We must love ourselves as God loves us -- despite our faults, in faith that the object of love can become worthy. In this way, we become agents of God's love in the world. This is not denial, but faith: faith that there is some good in the world that love can bring to fruition. And this is not some grand, abstract revolution but an aspect of our daily lives. We must love retail, not wholesale. The search for the redeemable in the world must dig deeply into the individuals and situations we encounter.

In this way, we bring meaning to a flawed world and redeem it. This is how we bring meaning to life and to our freedom: we use it to love others. O'Brien acknowledges the difficulties: that good is hard to find and that we are likely to bungle our efforts at loving others. He insists that we must proceed anyway, on faith.

I find his analysis penetrating, and his survey of the field enlightening. However, it leaves many questions: how exactly do we love what is flawed? How do we have faith that God does in fact love the world? How can we be conduits of God's love when we ourselves fall so short?

At one point, He offers the hope that his book will be a spiritual Amtrak to save religion from its current decrepitude. The book is copyrighted 1986. I wonder if he would have chosen a different metaphor in retrospect. Amtrak didn't really help things that much. Rail travel in the United States is still in sorry shape, for the same reasons it had been before Amtrak, reasons that Amtrak could not address. But then, Amtrak was a wholesale approach, not a retail one. A government bureaucracy as impersonal and uncaring as it gets.

Perhaps it's unrealistic to look for pat answers. Every solution, including O'Brien's, leaves some loose ends. What he has done for us is to narrow the search area, and to illuminate the terrain. The rest is up to us. We simply have to muddle through and figure it out as we go along. The problems of this life must be "lived through." Life is problems. Decide to enjoy the challenge.

This is religious existentialism, of the sort championed by Kierkegaard, before the atheists took over existentialist thought. It's not tidy; it rejects tidiness. It calls for faith, an idea that is offensive to skeptics. It insults the pride of transcendentalists and the worldly alike. Not everyone can accept this. But if no one has a better idea, why not give it a shot?

It's your call. It always was.