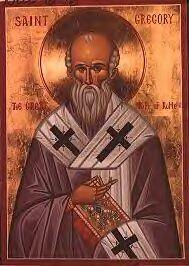

Gregory the Great: An Overview

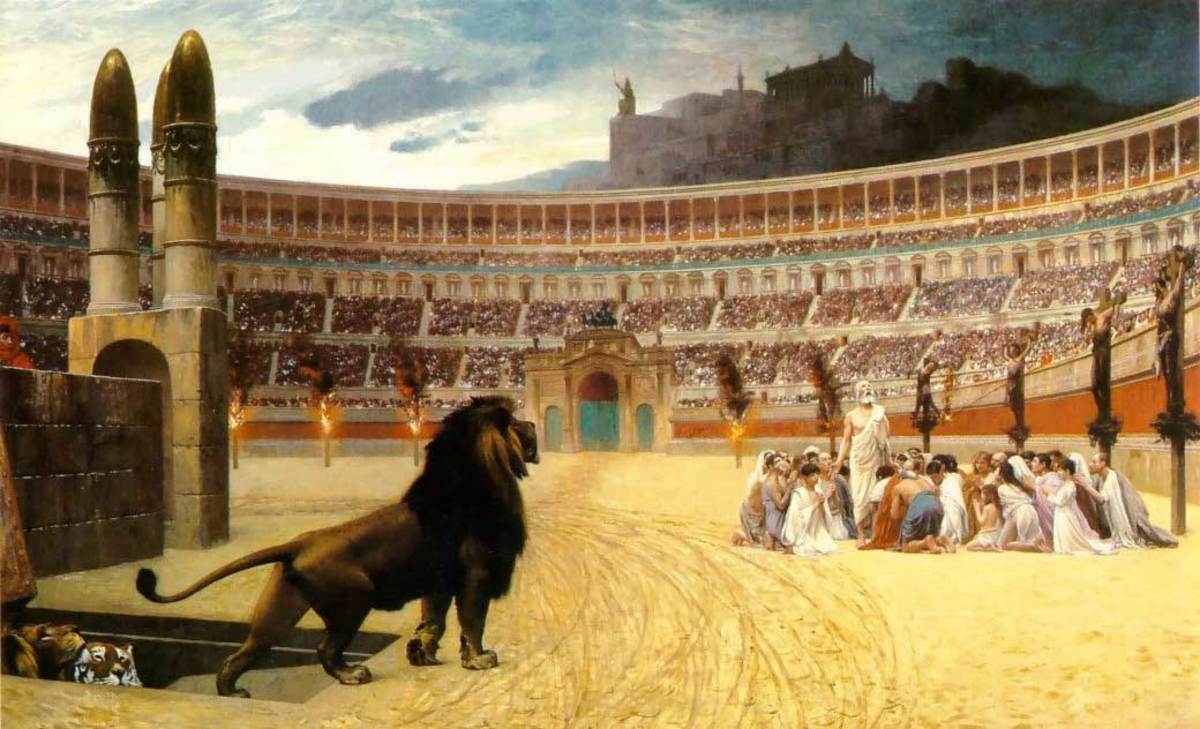

Western Rome in the 6th century was in disarray. The once unified and powerful Roman Empire was no more, as Italy saw itself beset by invading barbarian tribes and isolated from Eastern Rome’s center of power, Constantinople. After 476, the majority of the Western Empire had been ruled by Germanic kings, and Italy soon lay under the dominion of the Goths. Emperor Justinian’s ambition to retake the western half of his empire saw the return of Italy to Roman hands, but twenty years after a peace established by Justinian in 554, the so-called “plague of Justinian” swept through the land, and Italy was in a constant struggle against barbarian incursions, most notably by the Lombards.[1]

Within this volatile context lived Gregory, a man who would come to the papal throne in humility rather than ambition, and who saw in the barbaric armies of Italy’s foreign neighbors not men to destroy, but souls to win for Christ. While Gregory’s missionary methods were initially often crude and, by today’s standards, cruel, the mission sent to the England by Gregory under the leadership of Augustine of Canterbury could be fairly described as nearly as beneficial for Gregory as it was for the Angles he hoped to convert. Gregory’s devoted interest in England helped change the methods of Christian missionary work from coercive and forceful to tolerant and assimilative[2], and it was, arguably, the greatest legacy left behind by the appropriately titled, “Gregory the Great.”

[1] R.A. Markus, Gregory the Great and His World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 3-4.

[2] Though not, unfortunately, universally or permanently.

Gregory's Early Years

Gregory was born in the year 540 to a family who possessed both wealth and interest within the church. While not exactly aristocratic, Gregory’s family owned multiple properties and had a long history of holding church offices, as Gregory’s great-great grandfather, Felix III, ruled the see of Peter between 483-492 and his father Gordianus held a position as a minor officer.[1] Gregory’s education was most likely second to none in regards to what was available to those of his time. By his early thirties. Gregory held the post of urban prefect, a public service position that Gregory’s brother Palatinus would take over from him.[2] It is obvious from the responsibilities inherent in such a position that Gregory must have been a respected figure within his community. As Prefect, Gregory was expected to oversee much of Rome’s civic needs, “his duties being to superintend its financial affairs, watch over its buildings and its policing, provide food for the inhabitants, and preside over the senate. With the Lombards gradually encroaching upon their domains, it seemed to many citizens as though Imperial Rome was nearing its end.”[3]

[1] R.A. Markus, Gregory the Great and His World, 8-9.

[2] Carole Straw, Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection (Berkely, CA: University of California Press, 1988), 5.

[3] Bertram Colgrave (Trans.), The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 20.

Throughout much of Gregory’s writings, and indeed from his own actions, one can infer that monastic life was Gregory’s great passion, and were it not for the pressing demands of the world around him, Gregory would have most likely spent the majority of his life within the secluded and private world of the monastery. Gregory’s resignation from the post of urban prefect was precisely due to this love of monastic life. In 574, Gregory founded six monastic communities upon his estate, transforming his own home into a monastery dedicated to St. Andrew. Gregory’s idyllic monastic life was to end soon after, however, as Pope Pelagius called upon Gregory to serve as a deacon for the Roman Church, and soon thereafter, to be his representative in Constantinople, an ambassador to the city’s imperial court.[1]

[1] Carol Straw, Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection, 5.

Controversy with Euthychius

It should be noted that during Gregory’s ambassadorship in Constantinople, of which one of the greatest motivations for his being sent was surely to acquire military and financial help from Emperor Tiberius II against the incursions of the Lombards, history records one of Gregory’s battles against a erroneous belief of the day, battles which are often overlooked in light of the many other accomplishments of Gregory.

Eutychius, Patriarch of Constantinople, maintained that the resurrected body of a believer would be insubstantial, that it would be essentially lighter than air. This infuriated Gregory, who maintained that Christ’s own resurrection disproved this. Intervention by the Emperor was an eventual necessity to keep the peace between Eutychius and Gregory, with Tiberius siding with Gregory. Eutychius’ book on this subject was ordered destroyed, and both men were soon bed-ridden with serious illnesses. Gregory recovered, while the Patriarch did not. Though it is maintained that on his death-bed, Eutychius repented of his erroneous belief.[1]

[1] Gregory the Great, The Letters of Gregory the Great, Bertram Colgrave, trans. (Toronto: Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, 2004), 11.

Angles or Angels?

Approximately six years later, in 585, Gregory was recalled to Rome, his stint as ambassador to Constantinople over. Immediately upon returning to Rome, Gregory resumed his life within the tranquil confines of his monastery, studying the scriptures and living in contemplative communion with his fellow monks.

It was probably during this time that a formative event occurred in the life of Gregory, one that would greatly effect the future of England and Rome’s relationship to her. A well-known story concerning Gregory’s interest in the conversion of the Angles is told in The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, in which the anonymous author, a monk of Whitby, relates Gregory’s first exposure to these foreign people:

…there came to Rome certain people of our nation, fair-skinned and light haired, When he heard of their arrival he was eager to see them; being prompted by a fortunate intuition, being puzzled by their new and unusual appearance, and, above all, being inspired by God, he received them and asked what race they belonged to. They answered, “ The people we belong to are called Angles.” “Angels of God,” he replied, Then he asked further, “What is the name of the king of that people?” They said, “Aelli,” whereupon he said, “Alleluia, God’s praise must be heard there, “Then he asked the name of their own tribe, to which they answered, “Deire,” and he replied, “They shall flee from the wrath of God to the faith.”[1]

Gregory’s exposure to these Angles (whether they were free men or enslaved children) had had a profound effect on him. Tradition relates that soon after this meeting, Gregory appealed to Pope Benedict for permission to organize a missionary trip for himself and others to the land of England, hoping to share the gospel with a people whom Gregory assumed were steeped in paganism and who had little exposure to the Gospel. After being granted permission by Benedict, Gregory apparently made haste to the shores of England. The anonymous monk of Whitby relates an event in which, due to public demand, Gregory was denied his entrance into the land of the Angles:

So when it was announced that permission had been given, they (Romans) divided themselves in to three groups and stood along the road by which the Pope went into St. Peter’s Church; as he passed, each group shouted at him, “You have offended Peter, you have destroyed Rome, you have sent Gregory away.” As soon as he heard their dreadful cry for the third time, he quickly sent messengers after Gregory to make him return.[2]

As Prefect during such a tumultuous time, Gregory’s services to the city of Rome were considered invaluable by the Romans of his day. Hence, when news of his missionary zeal for the Angles and for his desire to personally lead a mission to their shores reached the ears of the Roman citizens the outcry for his immediate return would have been understandable. While Gregory was certainly passionate about spreading the gospel, he also recognized the authority of Pope , so when a party was dispatched to intercept Gregory and return him to Rome, Gregory begrudgingly, yet amicably, complied.[3]

[1] Monk of Whitby, The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, 91.

[2] Ibid., 93

[3] Monk of Whitby, The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, 93.

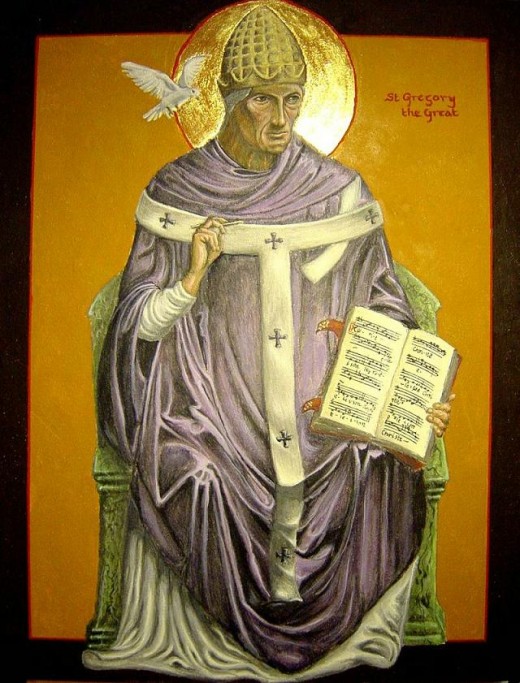

Ascension to Papacy

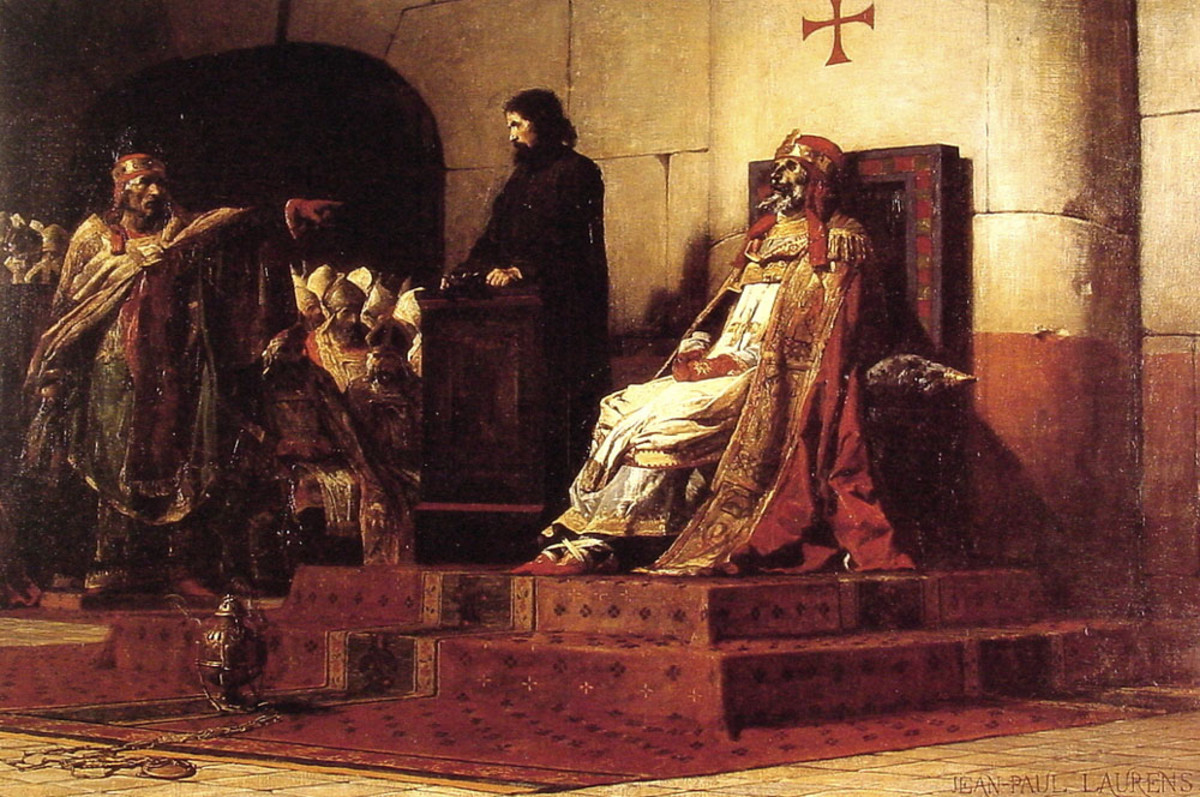

Upon Gregory’s return to Rome from Constantinople in 585, the majority of his days were spent in monastic pursuits, and from what one can ascertain from Gregory’s writings, this was his happiest time. So one can only imagine the frustration experienced by Gregory when in 590 both the general populace and the clergy alike called for Gregory’s accession to the position of Pope.[1] Just prior, an overflow of the Tiber River, which resulted in general destruction throughout Rome, resulted also in an outbreak of plague of which caused the death of Pope Pelagius. Given Gregory’s experience and evident success at the position of prefect, his election to the papal seat was an obvious choice. Gregory, however, was exceedingly displeased with this turn of events, and seemingly did everything in his power to avoid it.

So unlike the papal power-grabbing that would come to define much of the Roman Church in the centuries to come, Gregory resisted the office for reasons of his love of solitude before God, and the recognition of his own weakness in the face of such a grand responsibility. In Gregory’s own words, one sees a man of immense humility:

When I consider that I have been compelled to bear the weight of pastoral care although unequal to it in merit and totally resisting it in my mind, gloomy grief arises, and my sad heart see nothing other than those shadows, which allow nothing to be seen. For why is a bishop chosen before the Lord except to intercede on behalf of sinful people? And so with what confidence do I come before Him as an intercessor for other people’s when I am not secure about my own sins in his presence?[2]

Though his zeal for the people of England would not be extinguished, Gregory’s position as Pope saw more pressing and immediate needs to be addressed, namely, the plague that was ravaging Rome and the Lombard armies that were an ever-present threat to all of Italy.

[1] Carole Straw, Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection, 5.

[2] Gregory the Great, Letters of Gregory the Great, 135.

Gregory's Response to the Plague of 589

One of Gregory’s first acts as Pope was one of repentance. Viewing the plague, as did many presumably, as the “scourging of God” being meted out upon sinful mankind, Gregory’s call to repentance was intended to avert the wrath of God and in so doing, hopefully the plague would cease. After giving a speech to the citizens of Rome in which Gregory exhorted them to cry out to God and to “have a change of heart and pray that we have already been granted our request,” a procession throughout the city was then begun. Gregory of Tours, a contemporary historian and bishop, spoke glowingly of the procession, and miracles which accompanied it:

Gregory assembled the different groups of churchmen, and ordered them to sing psalms for three days and to pray to our Lord for forgiveness. At three o'clock all the choirs singing psalms came into church, chanting the Kyrie eleison as they passed through the city streets. As the procession reached the bridge over the River Tiber, the Archangel Michael appeared on the dome of Hadrian’s mausoleum with a flaming sword in his hand. He sheathed his sword and so put an end to the plague; hence the new name given to the mausoleum, Castel S. Angelo.[1]

[1] Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, Lewis Thorpe, Trans. (London: Penguin Publishers, 1974),Book X.

Gregory and the Lombards

Far more threatening, and to Gregory, hateful, than the plague, however, were the Lombards. A Germanic people that migrated south from Sweden, the Lombards first clashed, unsuccessfully, with the Roman Empire little more than a decade after the birth of Christ. Since their invasion of 568, the Lombard kingdom made itself a menacing presence within Italy, harassing the North with constant raids, and eventually establishing a dominant presence there by 590. Gregory’s opinion of the Lombards was hardly positive, and he reserved some of his harshest words for them throughout his writings, referring to them as “the unspeakable nation,” and described them as a people “whose promises are swords and whose favors are punishments.”[1] Given the inherently demanding roles which Gregory had held, it is understandable that such constant stress and anxiety caused by a hostile neighbor would have revealed a side of Gregory less than Christ-like. His requests for aid from the East during his time in Constantinople were unfulfilled due to the Empire’s Persian wars, and as Pope, there was rarely a time when the Lombards were not knocking on Rome’s door.

For a man ultimately concerned with peace and serenity, organizing Rome’s military against Lombard incursions was certainly not Gregory’s most passionate duty, but yet, as in all his endeavors, Gregory carried this out with fervor and resolve. And yet, Gregory’s main concern was always peace. In 593, King Agilulf and his armies arrived within the very walls of Rome, and besieged it.[2] It is not known how the siege was ended, but allegedly Gregory met with King Agilulf, and through a combination of diplomacy, charisma, and patience (and perhaps tribute!), Gregory persuaded the Lombard king to lift the siege.

Ultimately, Gregory’s great patience, diplomacy, and constant striving for peace with the Lombards once again displays the countenance of a man who was singularly preoccupied with his relationship with God. Historian John R.C. Martyn has this to say regarding Gregory and the Lombards:

In his relations with the Lombards, Gregory had achieved considerable success. He had strengthened what had remained of the Church in Lombard lands. He had obtained a truce between the Lombards and the Empire. And, finally, he had managed to see the heir to the Lombard throne baptized, not into the Arian faith or that of the Three Chapters faction, but into the Catholic faith as professed at Rome. Any one of these achievements would have been noteworthy. To have managed all three is quite remarkable.[3]

[1] R.A. Markus, Gregory the Great and His World, 100.

[2] R.A. Marcus, Gregory the Great and His World, 103.

[3] Gregory the Great, The Letters of Gregory the Great, 32.

Mission to England

Despite the multitude of responsibilities and dangers facing Rome during Gregory’s papacy, the issue of unconverted England never left his mind. While can assume that Gregory may have wished to lead the mission to the Angles himself, at this point in his life it would certainly have been a difficult, if not impossible, endeavor. So Gregory sent a band of missionaries to England in July of 596. Augustine of Canterbury, a prior of a Roman monastery, was chosen to lead this missionary group.

While Augustine certainly shared Gregory’s zeal for winning converts to Christ, he saw this journey to an unknown land full of pagan barbarians to be a terrifying ordeal, and as he and his group passed through Gaul and reached closer and closer to their destination, Augustine was convinced by his fellow missionaries to return to Gregory and request the whole ordeal be scrapped.[1] The Venerable Bede writes of the anxieties facing Augustine and his men, and of the response of Pope Gregory:

They having, in obedience to the pope’s commands, undertaken that work, when they had gone but a little way on their journey, were seized with craven terror, and began to think of returning home, rather than proceed to a barbarous, fierce, and unbelieving nation, to whose very language they were strangers; and by common consent they decided that this was the safer course. At once Augustine…was sent back, that he might, by humble entreaty, obtain of the blessed Gregory, that they should not be compelled to undertake so dangerous, toilsome, and uncertain a journey. The pope, in reply, sent them a letter of exhortation, persuading them to set forth to the work of the Divine Word, and rely on the help of God.[2]

Whether due to great encouragement, the requirements of obedience to the Pope, or a combination of both, Augustine and his men set forth again with renewed resolve, and in the spring of 597 reached the kingdom of Kent, first setting foot upon the Island of Thanet. What had apparently been unknown to both Gregory and Augustine was the Christian influence that had already existed among the peoples they initially contacted. Kent was at this time under the rule of King Ethelbert, whose wife, Queen Bertha, was of Frankish descent and who by all indications was already a Christian, keeping within her court the chaplain Liuthard, a Christian and a Gallic bishop. [3]

Augustine and his men were met with reserved hospitality, sending news of their arrival to King Ethelbert and being told to remain on Thanet for the time being. After a few days, Ethelbert met with them in the open air to discuss matters of the arrival. Bede tells us that Ethelbert was slightly suspicious of these foreign men, being concerned (according to a superstition) that were they to meet within the confines of a house, they could possibly cast spells upon him. Bede goes on:

When they had sat down, in obedience to the king’s commands, and preached to him and his attendants there present the Word of life, the king answered thus: "Your words and promises are fair, but because they are new to us, and of uncertain import, I cannot consent to them so far as to forsake that which I have so long observed with the whole English nation. But because you are come from far as strangers into my kingdom, and, as I conceive, are desirous to impart to us those things which you believe to be true, and most beneficial, we desire not to harm you, but will give you favourable entertainment, and take care to supply you with all things necessary to your sustenance; nor do we forbid you to preach and gain as many as you can to your religion.[4]

[1] R.A. Markus, Gregory the Great and His World, 158.

[2] The Venerable Bede, Ecclesiastical History of England, “Christian Classics.”http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bede/history.v.i.xxii.html (accessed Nov. 18, 2011).

[3] Gregory the Great, The Letters of Gregory the Great, 58.

[4] The Venerable Bede, Ecclesiastical History of England, v.i.xxiv.

Augustine’s fears, then, had been unnecessary, and after having established their good intentions with the king, he and his men were not only given full permission to preach the gospel, but were given provisions and were able to use old Roman churches within the capital city of Canterbury as both their church center and as a monastery.[1] One can imagine the worry experienced by Gregory during this time as he awaited news of Augustine’s success or failure. Like Augustine’s, Gregory’s fears too, had been unfounded, as in 601 a group of monks returned to Rome in order to obtain supplies for the burgeoning churches of Kent and to give Gregory much appreciated news of their success. Gregory responded by sending yet another party of monks to help with the growing mission, and by sending a letter to Augustine warning him of the dangers of pride, and a letter to King Ethelbert and his queen, exhorting them to increase in their zealousness for the faith, “overthrow the shrines; strengthen the morals of [your] subjects…by exhorting, by terrifying, by enticing, by correcting them, and showing them an example of good works.”[2]

[1] R.A. Markus, Gregory the Great and His World, 178-179.

[2] Ibid., 181.

As evidenced from this letter, Gregory’s missionary patterns prior to the conversion of England were hardly tolerant. Pagans who had either heard the gospel or who had converted were generally extended a fair amount of patience, but there was a limit to this grace. Within Christianized lands, Gregory expected cooperation from all authorities in extinguishing paganism. R.A. Markus writes:

Military commanders and civil officials were expected to bring pagans to the service of Christ. Those who would not mend their ways when admonished by the bishop’s preaching must be punished: slaves by beating and torture, freemen by being jailed and subjected to penance.[1]

Though it is unclear exactly why, Gregory evidently changed his policy on missionary practices during the conversion of England. The second group of monks to join Augustine were given instructions on new conversion practices to be implemented upon their arrival to the Angles. Gregory now pushed for assimilation rather than destruction of all pagan practices. Instead of the destruction of all shrines, they would now be blessed with holy water and filled with Christian relics and altars so as to encourage the pagan to continue worship in the same shrine, but rather to the one true God. While all idols were still to be destroyed, Gregory now believed that a less abrasive course of conversion would be more effective.[2] “This was a real turning point in the development of papal missionary strategy, and it was to shape missionary understanding for years to come.”[3]

The mission to England was a great success. King Ethelbert himself was baptized, and the foundations for the Christian faith were being laid increasingly throughout the land of the Angles. Gregory’s missional zeal for England was reflective of a man who was truly concerned for the souls of the lost, and whose humility allowed for self-reflection in those areas where Gregory may not have been conveying a true grace of Christ. Given the array of pressures that faced Gregory, and given his position of power, it is quite remarkable that history records not a man concerned with consolidating power or with destroying his enemies, but a man more concerned with living in accords with his faith, and pursuing a life defined by missional outreach.

[1] Ibid., 82.

[2] John R.C. Martyn, “The Letters of Gregory the Great,” 61.

[3] Ibid., 61.