H80 CG06Religious Realm

RELIGIOUS REALM

Introduction

Religion is a sacred engagement with that which is believed to be a spiritual reality. It is also a set of beliefs and practices designed to allow humans to achieved mental harmony with the powers of the universe, has been an essential aspect in the development of culture. Religion is also a worldwide phenomenon that has played a part in all human culture and so is a much broader, more complex category than the set of beliefs or practices found in any single religious tradition. An adequate understanding of religion must take into account its distinctive qualities and patterns as a form of human experience, as well as the similarities and differences in religions across human culture.

In all cultures, human beings make a practice of interacting with what are taken to be spiritual powers. These powers may be in the form of gods, spirits, ancestors, or any kind of sacred reality with which humans believe themselves to be connected. Sometimes a spiritual power is understood broadly as an all-embracing reality, and sometimes it is approached through its manifestation in special symbols. It may be regarded as external to the self, internal, or both. People interact with such a presence in a sacred manner—that is, with reverence and care. Religion is the term most commonly used to designate this complex and diverse realm of human experience.

The geographer is fascinated by these differences and by the interplay between a religious group’s beliefs and practices and the other facets of the culture within which that religion exist. The geographer wants to know why one culture can accept a set of beliefs while another culture rejects them, what role the environment plays in the development of a religion, and how religious beliefs structure the way people see and deal with the world. We will use the five themes to help answer these questions.

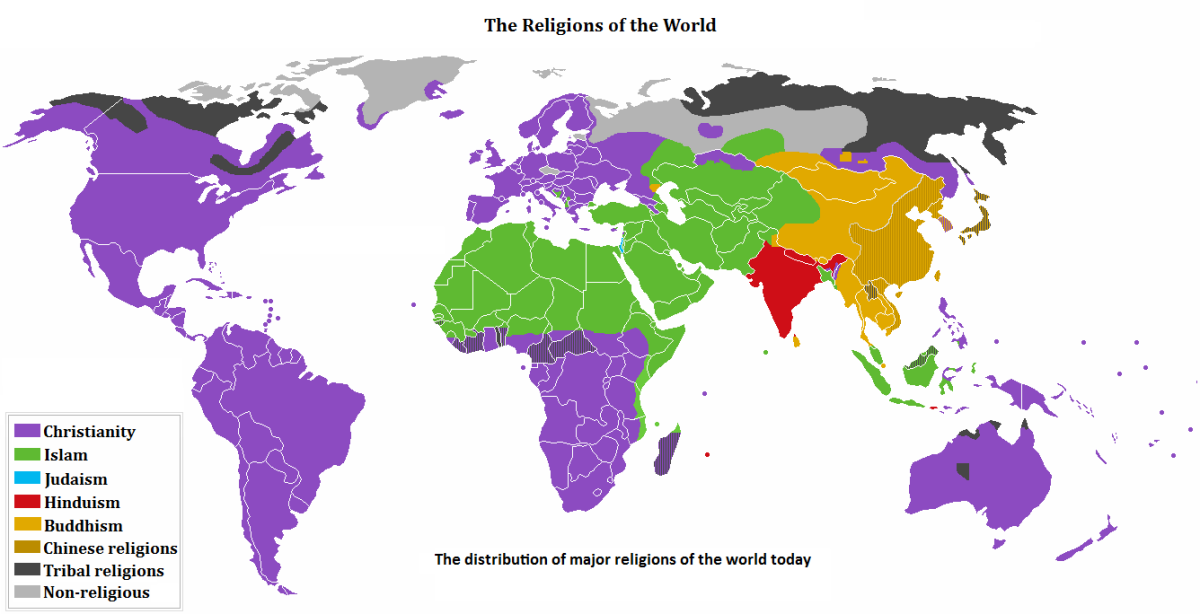

RELIGIOUS REALMS

Religious Culture Areas

We can devise all kinds of formal culture areas based on religion. We may, for instance, define religious culture areas on the basis of a single trait. We would find that much of the world is in such a culture area, since monotheism or the worship of a single god is typical of a number of major religions. We may choose instead to set up religious culture areas based on combination of traits-in other words to identify particular religions.

There are two major categories of religion both of which are further divided into various groups, sects, and dominations. The first category includes universalizing religions, those which actively seek new members and have as a goal of conversion of all humankind. Universalizing religions instruct their faithful to spread the Word to all the earth, using one method or another to convert the heathen. Contrasted to universalizing religions are ethnic religions, each of which is identified with some particular ethnic or tribal group and does not seek converts. This change usually occurs within an ethnic religion when a charismatic leader or reformer emerges, whose revelations are so profound and whose personality is so dynamic that persons beyond the immediate cultural group are attracted. Once the evangelical spirit of such universalizing religion is spent a fragmentation and reversion to ethnic status sometimes occurs.

Christianity

It is the most widely distributed of the world religions, having substantial representation in all the populated continents of the globe. Christianity is in many ways comprehensible only “from the inside,” to those who share the beliefs and strive to live by the values; and a description that would ignore these “inside” aspects of it would not be historically faithful. To a degree that those on the inside often fail to recognize, however, such a system of beliefs and values can also be described in a way that makes sense as well to an interested observer who does not or even cannot, share their outlook.

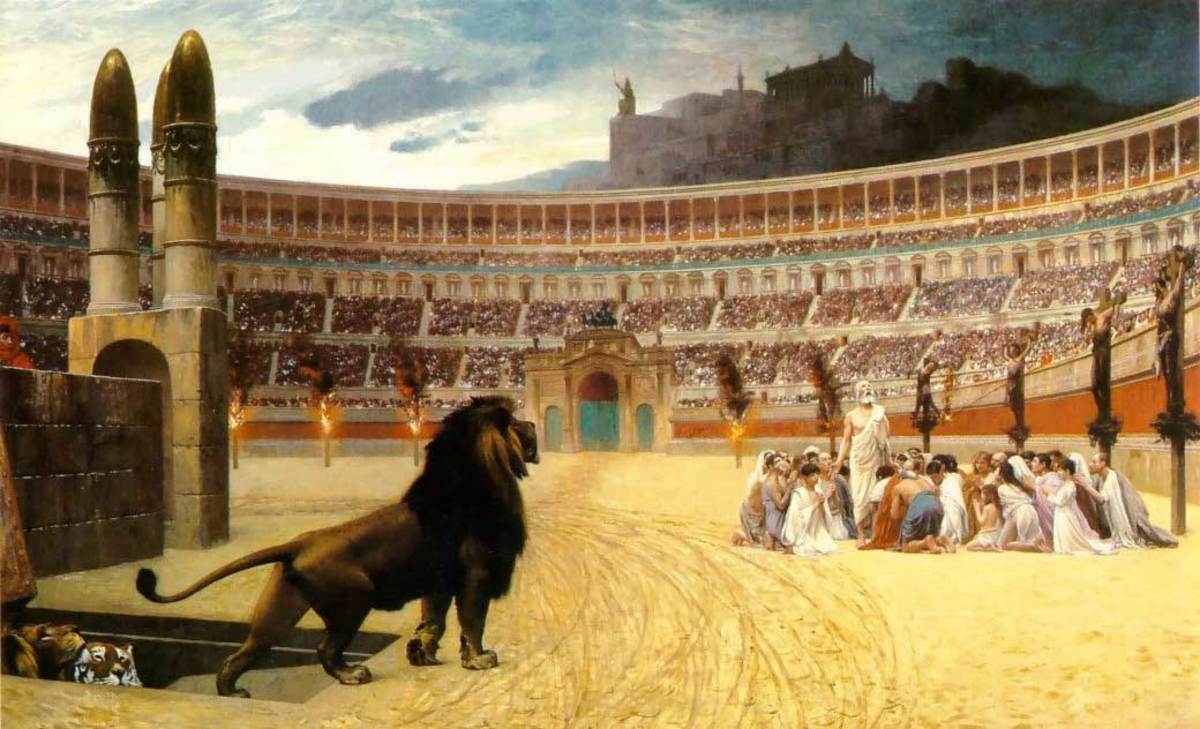

Jerusalem was the center of the Christian movement, at least until its destruction by Roman armies in ad 70, but from this center Christianity radiated to other cities and towns in Palestine and beyond. At first, its appeal was largely, although not completely, confined to the adherents of Judaism, to whom it presented itself as “new,” not in the sense of novel and brand-new, but in the sense of continuing and fulfilling what God had promised to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

At a very early date, however, Christianity began to fragment into separate churches. The first major schism, which took place between Eastern and western Christianity, became final in 1054 AD when the Eastern leaders excommunicated by the Roman Pope. The Eastern Church, in turn, split repeatedly into a number of local Christian groups. One of these, the Eastern Orthodox Church, found mainly in the Greek and Slavic speaking areas of eastern and southeastern Europe, fragmented into a variety of national sects, including Greek Orthodoxy, Russian Orthodoxy, and the Armenian church of the Russian-Turkish borderland. Other branches of Eastern Christianity include the Coptic Church, originally a nationalistic church of Christians Egyptians. Remnants of the Nestorian Church, derived from an even earlier “heresy” concerning the dual personality of Christ, can presently be found in the mountains of Kurdistan north of the Fertile Crescent and in India’s Kerala State. The Nestorian Church was largely destroyed by the Asiatic conqueror Tamerlane in the Middle Ages.

The Western or Roman Catholic Church rose to prominence in western and central Europe by sending missionaries to convert the Germanic and Celtic peoples. Western Christianity splintered also, most notably in the Protestant breakaway of the 1500’s. Since then, the Roman Catholic Church has remained strongly unified, but Protestantism has tended from its beginning to divide into a bewildering array of sects. Both Catholic and Protestant missionaries have worked tirelessly to spread Christianity to other parts of the world. The numerous faiths imported from Europe were later joined by the Christians sects developed in America. The American frontier was a special breeding ground for new religious groups, as individualistic pioneer sentiment made its voice heard in new Christian denominations. The number of denominations in the United States today is staggering. Moreover, many of these groups, though united at the national level, are split at the regional congregational level.

Islam

Islam is one of the three major world religions, along with Judaism and Christianity that profess monotheism, or the belief in a single god. In the Arabic language, the word Islam means “surrender” or “submission”—submission to the will of God. A follower of Islam is called a Muslim, which in Arabic means “one who surrenders to God. Islam claims perhaps as many as 500 million followers. Like Christianity, Islam originated among Semites of the Middle East. It arose in western Arabia in the eighth century. With militant fervor, Arabs spread it westward across North Africa and eastward through the Fertile Crescent. Arab warriors also carried Islam into the Indo-European-populated highlands of the Middle East, mainly Iran and Afghanistan, and beyond into the Indus Plain of the Indian subcontinent.

Although it is not as severely fragmented as Christianity, Islam too, has split into separate groups. Two major sects prevail: the Shiah Muslims, living mainly in Iran and parts of Iraq and numbering about 50 million, and the Sunni Muslims, forming most of the remaining majority within the Islamic world. Originally, these two groups disagree on the proper method of appointing a successor to Muhammad after his death.

Judaism

Is a religious culture of the Jews (also known as the people of Israel); one of the world’s oldest continuing religious traditions, the oldest monotheistic faith, is the parent of Christianity and is closely related to Islam. In contrast to the other monotheistic faiths, Judaism does not actively seek new converts and has remained an ethnic religion throughout most of its existence.

The terms Judaism and religion do not exist in pre modern Hebrew. The Jews spoke of Torah, God’s revealed instruction to Israel, which mandated both a worldview and a way of life—Halakhah. Halakhah derives from the Hebrew word “to go” and has come to mean the “way” or “path.” It encompasses Jewish law, custom, and practice. Pre modern Judaism, in all its historical forms, thus constituted (and traditional Judaism today constitutes) an integrated cultural system encompassing the totality of individual and communal existence.

Judaism originated in the land of Israel (also known as Palestine) in the Middle East. Subsequently, Jewish communities have existed at one time or another in almost all parts of the world, a result of both voluntary migrations of Jews and forced exile or expulsions. In the late 1990s the total world Jewish population was 14.1 million, of whom 5.9 million lived in the United States, 4.6 million in Israel, and 700,000 each in France and Russia, the four largest centers of Jewish settlement. About 500,000 Jews lived in Ukraine, 350,000 in Canada, 300,000 in the Great Britain, 250,000 in Argentina, and 100,000 in South Africa. These figures indicate that 42 percent of the Jewish population resides in North America, followed by Asia with 29 percent, Europe (including Russia) with 18 percent, Latin America with 8 percent, Africa with 2 percent, and Oceania with 1 percent.

Hinduism

Is a religious tradition of Indian origin, comprising the beliefs and practices of Hindus. The word Hindu is derived from the river Sindhu, or Indus. Hindu was primarily a geographical term that referred to India or to a region of India (near the Sindhu) as long ago as the 6th century BC. The word Hinduism is an English word of more recent origin. Hinduism entered the English language in the early 19th century to describe the beliefs and practices of those residents of India who had not converted to Islam or Christianity and did not practice Judaism or Zoroastrianism. Hinduism spread from the Punjab region to dominate the entire Indian subcontinent.

Hinduism is decidedly polytheistic involving hundreds of deities. It also includes features such as the caste system, a rigid segregation of people according to ancestry and occupation; the belief in reincarnation; and the veneration of all forms of life, called ahimsa, with severe restrictions on killing and eating animals of any kind. However, no standard set of beliefs prevails, and Hinduism has many local forms. Some Hindus are actually monotheistic, others permit the eating of fish, still others venerate military prowess and are highly skilled soldiers.

Buddhism

It is begun in the Himalayan foothills of northern India about 500BC as a reform movement within Hinduism. Its founder was Prince Siddhartha Gautama , later known as the Buddha. It is based on the four “noble truths”: life is full of suffering; desire is the cause of this suffering; cessation of suffering comes with the quelling of desire; and an “Eight-Fold Path” of proper personal conduct and meditation permits the individual to overcome desire. As in Hinduism, escape from sorrow of mortality is the goal of Buddhism. The resultant state of escape and bliss is known Nirvana.

For centuries, Buddhism remained confined to the Indian subcontinent, but missionaries later carried Buddhism to China (100 BC-AD 200), Korea and Japan (AD 300-500), Southeast Asia (AD 400-600), Tibet (AD 700), and Mongolia (AD 1500). Like Christianity, Buddhism almost completely disappeared from its place of origin, its followers beings slowly reabsorbed into Hinduism. In China and Japan, Buddhism fused with the native ethnic religion such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Shintoism to form composite faiths. Along with Christianity and Islam, Buddhism remains one of the three great universalizing religions in the world.

Animism

Tribal peoples who do not adhere to any of the world’s major ethnic or universalizing religions are usually referred to collectively as animist believe that certain inanimate objects possess spirits or souls. These animistic spirits live in rocks and rivers, mountain peaks and heavenly bodies, forest and swamps. Each tribe has its own characteristic form of animism and has vested a particular set of objects with spirits. Usually a tribal religious figure serves as an intermediary between the people and the spirits.

Animism is in retreat almost everywhere. It survives in remote areas where tribal peoples have sought refuge, such as interior Africa, the Amazon Basin, and the mountains of New Guinea. However, many animistic beliefs still survive in universalizing religions.

Secularized Areas

In some parts of the world, especially in urban and industrial areas, traditional religions are declining. Secularization is taking place in lands as different as India, the Netherlands, and the Soviet Union. In some Instances the retreat from organized religion has resulted from a government’s active hostility toward a particular faith or toward religion in general. Whatever the reason, people are leaving their traditional religions in growing numbers.

Quasi-Religions, or systems of belief similar to religions but lacking worship services often fill the emotional vacuum produced by secularization.

RELIGIOUS DIFFUSION

Religions are spread in two ways, first the relocation diffusion, it is the method of the universalizing the religions, who send missionaries to new lands. Second is the expansion diffusion, it can be subdivided into hierarchical and contagious types. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas are implanted at the top of a social structure and spread down town later. The contagious diffusion means the spread of ideas in the manner of contagious diseases by personal contact through area and population without regard to hierarchies.

RELIGIOUS ECOLOGY

One of the main functions of many religions is the maintenance of harmonious relationship between people and its physical environment. Naturally then, the physical environment has had a particularly powerful influence on the development of various religions. Environmental influence readily apparent in the tribal animistic faiths. Animistic nature-spirits lie behind certain practices found in the great religions, such as the veneration of rivers, mountains, rocks, and forest. For instance, the Ganges River is holy to the Hindus and the Jordan River for the Christians. In veneration of high places, for example, Mount Fujiyama, sacred in Japanese Shintoism, and holy volcanoes in Mexico. Rock and stones, example, the famous Black Stone at Mecca, has a special significance for the Muslims. Evergreen trees for Christians in Christmas celebrations and plant evergreens in cemeteries as symbols of everlasting life.

The Environment and Monotheism

The three major monotheistic faiths-Christianity, Islam, and Judaism all have their roots among the desert dwellers of the Middle East. Lamaism, the most nearly monotheistic form of Buddhism, flourishes in the desert of Tibet and Mongolia. In all of these cases, the people involved (Hebrews, Arabs, Tibetans, and Mongolians) were once nomadic herders, wandering from place to place in the desert with flocks and herds of livestock.

Religion and Environmental Modification

Just as the physical environment can influence religious belief and practice, so the religious outlook of a people can help determine how they will modify their environment. The Judeo-Christian teleological view of the world provides a splendid example of this. Teleologists believe the earth was created especially for humans. Within the teleological view is the belief that humans are not part of nature, but are separate, forming one member of a God-Nature-Human trinity.

Believing that the earth was given to humans for their use, Christians thinkers in medieval Europe adopted the view that humans were God’s helper in finishing the task of creation.

Religion and Environmental Perception

Religion can also influence the way people perceived their physical environment. Nowhere is this more evident than in the perception of environmental hazards such as floods, storms, and droughts. Hinduism and Buddhism teach followers to accept such hazards without struggle, to regard them as natural and unavoidable. Christians are more likely to view storm, flood, or drought as unusual and preventable. As a result, they will generally take steps to overcome the hazard.

CULTURAL INTEGRATION IN RELIGION

Spatial variations in religious belief influence are influenced by social, economic, and political patterns in countless ways. Religion and languages often travel together and religious belief is sometimes at the root of nationalism. In the economic sphere, religion can determine what crops and livestock are raised by farmers, what foods and beverages people consume, even what type of employment a person has.

RELIGION AND ECONOMY

People make their living in many different ways, and these forms of livelihood vary greatly from one area to another. Religion is partially responsible for these variations.

Religion and Agriculture

Within some religions, certain plants and livestock, as well as the products derived from them, are in great demand because of their role in religious ceremonies and traditions. When this is the case, the plants or animals tend to spread with the faith.

Religion also can often explain the absence of individual crops or domestic animals in an area. The environmentally similar lands of Spain and Morocco, separated only by the Strait of Gibraltar, show the agricultural impact of food taboos. On the Spanish (Roman Catholic) side of the strait, pigs are common, but they are not found in Muslim Morocco on the African side. The Islamic avoidance of pork underlies this contrast. Judaism also has restriction against pork and other meats.

Religion and Fishing

Christian tradition has always honored fishermen. We can perhaps trace this back to the apostle Peter, a fisherman by profession. The fish was an early symbol of Christianity. Other cultures place religious taboos on fish consumption and produced an opposite economic result. Most Hindus will not eat fish. India regularly suffers food shortages and dietary deficiencies while the nearby ocean teems with protein-rich fish. Among the Christians, the Seventh - day Adventists have established a fish taboo. When missionaries of this church converted the population of Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific to their faith, the island’s economic self-sufficiency collapsed, because the people had previously depended heavily on for their diet.

Religious tourism: The Pilgrim Trade

For many religious groups, sites of particular importance to the faith have become the goal of pilgrimages. Pilgrimages are typical of both ethnic and universalizing religions. They are particularly significant to followers of Islam, Hinduism, Shintoism, and Roman Catholicism. Example sites include the Arabian cities of Mecca and Medina in Islam; Rome and the French town of Lourdes in Roman Catholicism; the Indian city of Varanasi on the holy Ganges River, a goal of Hindu pilgrims; and Ise, the heart of Shintoism in Japan.

Pilgrimages can have tremendous economic impact, since the movement of pilgrims amounts to a form of tourism. In some favored localities, the pilgrim trade provides the only significant source of revenue for the community.

Religion and profession

Often religion and employment are closely connected. In Hinduism, persons in each caste traditionally had a prescribed economic role to play. To follow any occupation other than that dictated by caste was a violation of moral obligations. The caste system apparently originated about 1500 BC when Indo-Europeans invaded and conquered northern India.

In medieval Europe, Christians were generally restricted from loaning money for interest. Jews, outcast in Christian Europe, found most professions closed to them by law. As a result, while most of the Jewish population remained in abysmal poverty, individual Jews found an economic niche as moneylenders. Then they used this occupation as a capitalist foothold from which they developed skills as retailers, and in time some even became important businessmen.

Religion and Political Geography

In some nations, religion has been the rallying point for nationalistic sentiment and has even provided a justification for national existence. Israel and the Republic of Ireland are two other nations based on religion. In Israel automatic citizenship is available only to Jews. In cases where religion is an important basis of nationalism, a state church is often created. Such a church is recognized by law as the only one in the state and the government controls both church and state.

In still other case, the church is actively involved in governing countries. Such a government is known as theocracy. The head the church is also often the head of state. The Vatican City, ruled by the Pope, is fully independent state occupying parts of Rome. In some nations political parties are linked to particular church groups. Even in countries like United States where legal separation of church and state is maintained, voting patterns often correspond to religion.

Religious Landscape and Structure

Religion form as an integral part of cultural landscape. Its places of worship, cemeteries, settlement patterns, and place names are imprinted on the countryside.

The most obvious religious contributions to the landscape are the buildings erected to house divinities or to shelter worshipers. These structures vary greatly in size, function, style of architecture, construction material, and degree of ornateness. To Roman Catholics, the church building is literally the house of God, and the altar is the focus of vitally important ritual. Partly for these reasons, Catholic churches are typically large, elaborately decorated, and visually imposing.

To most Protestants, on the other hand, the church is simply a place to assemble for worship. God visit the church, but does not live there. The simpler church buildings of Protestantism appeal less to the senses and more to the personal faith.

Muslims and Jews rely much less on sanctified houses of worship than do Christians. In Muslim areas, the minaret, the needlelike tower from which the faithful are called to worship, takes precedence over the mosque as the major feature of the religious landscape. Jews who have lived as a minority group among Christians for many years are often influenced to build impressive, churchlike synagogues, but these buildings represent a break with Jewish tradition.

Hinduism has produced large numbers of visually striking temples for its multiplicity of gods, but much worship is practiced in private households. Another Hindu landscape feature is the wayside shrine with the image god or goddess adorned with flowers.

Landscapes of the Dead

Religions differ greatly in the type of tribute they award to the dead. Hindus, Buddhists, and Japanese Shintoists cremate their dead. Having no cemeteries, their dead leave no mark on the land. In the same way, the few remaining Zoroastrians (called Parsees), who preserve a once-widespread Middle Eastern faith now confined to parts of India, have traditionally left their dead exposed to be devoured by vultures. In Egypt, spectacular pyramids and other tombs were built to house dead leaders. Christians, Muslims, and Chinese who practice the composite Confucianist-Buddhist religion typically bury their dead, setting aside land for that purpose and erecting monuments to the deceased kin.

Religion and Rural Settlement Pattern

Most farming live either in dispersed farmsteads separated from one another or in clustered settlements such as villages. Religion often helps determine which of these patterns will prevail. In the United States and Canada, many highly cohesive religious groups have traditionally formed village settlements, in contrast to the more typical American pattern of dispersed farmsteads. The farm village tradition in Anglo-America was introduced by the Puritans of New England and later perpetuated by Mennonites in Canada and Mormons in the Great Basin of the American West.

Religious Names on the Land

Religion often inspires the names people give to the land. Within Christianity, the use of saints’ name for settlements is very common in Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox areas, especially in overseas Catholic colonial lands such as Latin America and French Canada. Names beginning with the prefixes saint and sainte are numerically dominant in French Catholic portions of Quebec.

CONCLUSION

Religion, like language, is firmly interwoven in the fabric of culture, a bright hue in the human mosaic. Religions and individual religious elements vary greatly from one area to another. Several major religions and many minor ones form a variety of culture areas. We illustrated these spatial variations on maps.

Such religious spatial variation led us to ask how these distributions came to be, a question best answered through the methods of cultural diffusion. Some religions, universalizing denominations, actively encourage their own diffusion. Most Christian churches, for example, send out missionaries to “spread the word”. Others erect barriers to expansion diffusion by restricting membership to one particular ethnic group. Jews, for instance, do not seek converts. The spatial diffusion of religious ideas often parallels and accompanies other, nonreligious elements of culture, such as language, crops, and political systems.

The theme of cultural ecology reveals some fundamental ties between religion and the physical environment. One major function of many religious systems, particularly the animistic faiths, is to appease and placate the forces of nature and to achieve harmony between the people and the physical environment. Religions differ in their outlook on environmental modification by humans; Christianity incorporates the doctrine that environmental alteration is good and is the will of God. Thus Christians, assuming divine approval, cleared forest, drained marshes, and plowed native grassland. Other religious groups view such alterations as an affront to the gods. We need to face the question of whether the Christians ecological outlook is leading us to environmental disaster.

From cultural integration we learned that religion is causally related to economy and politics. Everything from tourism to nationalism can be a religious component. This further strengthens the view of culture as functioning whole.

The cultural landscape abounds with expressions of religious belief. Places of worship-temples, churches, and shrine-differ in appearance, distinctiveness, prominence, and frequency of occurrence from one religious culture to another. These buildings provide a visual index to the various faiths. Cemeteries and religious place names also add a special effect to the landscape that tells us about the religious character of the population.

Here our focus shifts to two chapters economic topics-agriculture, and industry and transportation. However, the shift is not very great, for the way people earn their living is very much a part of their culture. We have already seen how religious taboos on food affect agriculture. Population settlement, political system, and life styles add more modifications to human economic activities. The way people provide for their material needs is as much product of culture as religious beliefs and linguistic variations. The farm, the factory, and the highway all express biases of our culture.

Ardin J. Odoy, Norjehan M. H.Najib, Mohammad and Nabel Disomimba Luma