How Should Christians Approach Muslims and Muslim Converts to Christianity?

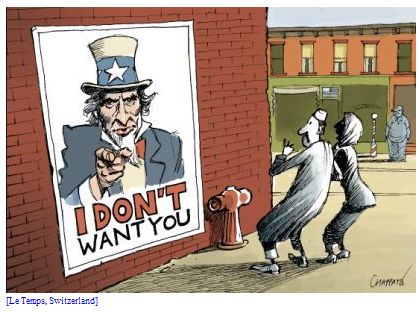

A cursory glance at the comment boxes accompanying internet articles on nearly anything related to Islam reveals that strong anti-Muslim sentiment has more than arrived in America, it has become entrenched. And all too often, it is those who identify with an Evangelical Christian worldview who staunchly support such a sentiment. In our post- 9/11 world, the overall attitude towards Muslims has shifted considerably. They are no longer seen as merely 'the other,' they are 'the other' who wish us harm, who hate our way of life and who desire the global implementation of Sharia law. In this context, the culture which accompanies the Muslim is equally deserving of suspicion and dislike. After 1400 years of Islamic influence upon the Middle East, Islam and culture are inextricably intertwined. Arabic is the language in which the Qur'an was written and the language of which all practicing Muslims are expected to learn. Muslim men often style their dress, their hair, even the length of their beards on how the Prophet Mohammed appeared, and Muslim women often cover their hair or face as a means of being faithful to the recommendations given by the Qur'an.

When a Muslim accepts Jesus Christ as their Lord and savior, he or she is often faced with a requirement to expunge all vestiges of their cultural identity in order to find acceptance within another culture: the Evangelical church. Here, there is no more mention of Allah, no more repressive hijabs, no more chants, in fact even one's name should be changed- for how can a young man worship Jesus correctly when his name pays homage to Mohammed? In this paper I will argue that while churches who attempt to implement this approach to evangelizing among Muslims may have pure motives, their actions fall far short of what I believe is a biblical standard. Whether a church exists in an overseas missional context- embedded in the culture around it- or if it is of the home-grown variety of evangelical churches right here in the United States, similar cultural challenges face each church: How can we show respect to the culture of those from a Muslim background while retaining the aspects of our church necessary for orthodox theology?

You're Doing it Right

Dr. Nabeel T. Jabbour addresses this issue in his book, "The Crescent through the Eyes of the Cross." In it, Dr. Jabbour, an Arab Christian who has spent the majority of his life in the Middle-East, interviews numerous Muslims who express their fears, suspicions, and doubts regarding the Christian church existing in a Western context. A young Egyptian woman by the name of Fatima Abdul Mun'im responded to the expectations of many Western Christians that she adopt their culture instead of retaining her own:

...it is unthinkable for us to give up our culture in order to adopt the European or American culture and become Christians. We are people with deep roots in a civilization that goes back at least five thousand years. Why should we be uprooted from our families, our culture, and our natural place of belongingness?1

1Fatima Abdul Mun'im, Nabeel T. Jabbour, author, The Crescent Through the Eyes of the Cross (Colorado Spring, CO: NavPress, 2008), 69.

For me this issue hits close to the heart, as a dear Muslim friend of mine has faced this very dilemma, and sees the evangelical church's expectations of Muslim converts disconcerting. Even beyond this, however, is the existence of a deep cultural ignorance which is wholly unaware of the major ramifications behind conversion for many Muslims. Over the years, my friend, I'll call him Ahmad, has shown an increasing curiosity for the gospel message and for the Jesus of the Bible. In fact, his own doubts concerning the holiness of Mohammed and the validity of the Qur'an have led to a disinterest in performing his five daily prayers, or salat, reading from the Qur'an. Indeed, it seems these days, Ahmad retains the title of "Muslim" in name alone. So what keeps him from accepting the life-affirming message of Jesus Christ?

It is quite difficult for Christians living within the context of modern America to understand real persecution or ostracism. Oftentimes, the greatest threat we face by sharing our faith with others is that we will experience a moment of social awkwardness. For Ahmad, however, and millions of Muslims the world over, the acceptance of Jesus Christ carries with it two very real possibilities: Abandonment and ostracism by one's family, and physical harm, imprisonment, or death.1 Without citizenship, a public conversion to Christianity by Ahmad would see swift repercussions. If he was able to remain in the States, he could avoid imprisonment and/or execution by the Saudi Arabian government. But his father, his mother, his sister and all other relatives would very likely never speak to him again. Could we have made this sacrifice for Jesus before we had known him? Could I?

I would argue that given these realities- the deep cultural identity of the Arab people coupled with the threat of persecution for conversion- our response to Muslims and to new believers needs to be aware and intelligent enough to approach the situation in a wise and godly manner. It is important to be aware that the new convert could experience the same feelings of shock and awkwardness that would accompany an American visiting a mosque in Cairo. Sadly, it appears the majority of American evangelical Christians today use a combined approach of disarming "niceness" with a variety of demands regarding the former belief system of the ex-Muslim. Oftentimes, these demands revolve around the dress and language of the Arab, two of the most fundamental aspects of any culture.

1 Dr. Christine Schirrmacher, "Defection from Islam: A Disturbing Human Rights Dilemma." Institut fur Islamfragen .http://islaminstitut.de/uploads/media/Apostasy2.pdf (accessed April 13, 2013).

Good Reads Courtesy of Multnomah Seminary

What of the hijab, or head scarf worn by so many Muslim woman? For many in the West, this signifies not a statement of personal modesty, submission to God and a refusal to engage in promiscuity, but rather the repression of women's rights. Curiously, I wonder what our response would be to see Mary, the mother of Jesus, walking among us similarly cowled, or of any individual woman belonging to the early church, a church we continue to hold as the greatest attainable standard we could possibly reach?

A woman who has covered her hair for most of her life as a means of displaying her modesty and devotion to God could be shamed and deeply embarrassed by removing her hijab. Fatima in The Crescent through the Eyes of the Cross speaks of her head scarf in terms of great personal significance:

Nobody in my family asked me to wear the hijab. I do not feel oppressed as I wear it. On the contrary, I feel empowered. I communicate the message that I am not cheap or sexually available. I take pride in our Muslim heritage and culture.1

1 Nabeel T. Jabbour, The Crescent Through the Eyes of the Cross, 72.

Greg Daniels in an article in Christianity Today titled, "Worshiping Jesus in the Mosque," interviewed a young man who shared his own frustrations in trying to meet the cultural expectations of those within the church

One day the pastor came to me and said, "How are you?" I answered, "Alhamdulillah!" ("Praise be to God!"). The pastor was very angry. He said, "No, brother! No more Alhamdulillah. Your God is changed from Allah to God [using the tribal name]. You have to express your thanksgiving to God as a Christian, and we have our own expression of thanksgiving to God." He ordered me to say, "Praise the Lord" and "Praise to God." He asked me to not use the term Allah because Allah is evil, Allah is the Devil, Allah is the black stone, Allah is an idol. That was the first time I had heard [anyone say] that Allah is an idol or evil. I was shocked. When I do my spiritual duties, I think I am doing them for Allah. He is the one who created the universe, sustains the universe, and judges the universe. I couldn't in my mind imagine that Allah is an idol or evil.1

By attacking the Arabic word for God in this way, Christians undermine perhaps their greatest tool in engaging in dialogue with Muslims and new converts. For Muslims, Allah is the same god who talked to Abraham and who led the Israelites out of Egypt. He is the same god worshiped by Jews and Christians alike, and therefore, the one great common denominator with which both Muslims and Christians can speak of with reverence and adoration. At the end of the day, Muslims do not believe they are worshiping an evil idol, they believe they are worshiping Yahweh. As the young man said, "If you tell a Muslim about the Creator of heaven and earth, but say that the Creator is not Allah, the Muslim will be very confused. What you are telling him is not good news."2

1 Greg Daniels, "Worshiping Jesus in the Mosque," Christianity Today, January/February 2013, Vol. 57, No. 1, 22.

2 Ibid., 22.

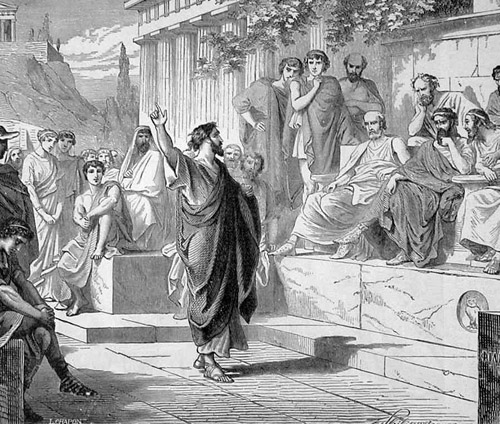

A striking example of an extremely similar scenario, and in fact a far more extreme circumstance, is found in Acts whereas Paul brought to attention the unknown god worshiped by the Athenians. Unlike Muslims, the Athenians had no connection to the god of Paul, and most certainly worshiped their unknown god in ways fully pagan. It is amazing how often we overlook the example of Paul in this circumstance. Did he condemn the Athenians for their pagan worship? Did he demand that their culture -even where it was clearly in disobedience to God- adapt to that of the Jews and the early church? Hardly. Paul instead used their idols as a means to establish common ground, illustrating the truth of the Creator through a lens which they could understand.

Of course, it should be pointed out that in no way am I arguing that the specific culture of the Western Evangelical church should change to accommodate others. If this were the case, a church would be impossible to define culturally, being constantly morphed and remorphed into whatever cultural paradigm the church saw as proper at that given time. But the church can go a long way in helping a new convert, or a curious Muslim attender, to feel accepted not as simply a potential new member, but as a unique human being created in the image of God with a unique perspective and culture.

A Person, not a Project

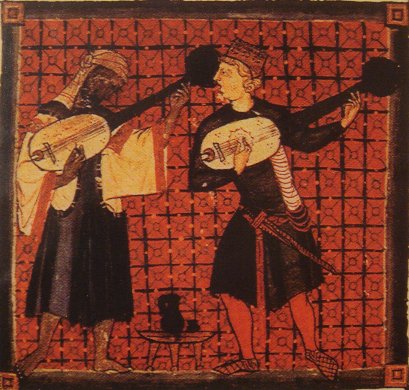

I see two very realistic actions which need to take place in order to foster a spirit of love and acceptance towards not only Muslim converts to Christianity, but our Muslim brothers and sisters as well. First, recognize that a new believer from the Middle-east does not come from an inferior culture which requires our sympathetic charity. He or she rather has a wealth of cultural experiences which can often be enlightening and put many of our own practices to shame. Second, potential church plants (or even established churches) by westerners which identify with Middle-eastern culture or which are planted in a Middle-Eastern country should not be intent on embracing the trappings of their own paradigm for fear that it will not be truly Christian. Nowhere in the Bible do we see commands to follow a specific architectural plan for our church, to sing a certain kind of music, to dress a certain way, or to even meet only on Sunday. A church planted with Arab culture in mind is in no way restricted by the Western Evangelical model of folding chairs or pews, contemporary Christian rock bands, or Sunday morning worship. In fact, during my time spent within a historic mosque in the city of Cairo, I was amazed at the sense of sacredness which pervaded the interior. Smells of incense, beautifully woven carpets, pillows upon which to sit and a sombre silence all contributed to producing a space within which to worship.

The Middle-eastern Muslim convert to Christianity presents a certain paradox to the Christian church. The question on the minds of many Western Christians is this: Is there a point in which the expectations placed upon a church by a culture shaped largely by Islam cannot be accepted as mere cultural idiosyncrasies? Or, as Phil Parashall, a missionary serving in Bangladesh asks, "How much contextualization is too much?" Phil described his approach and some common concerns in an article he wrote for Christianity Today titled, "How Much Muslim Context is too Much for the Gospel?":

Our goal was to be biblically orthodox and maximally attractive to our Muslim audience. We adopted some forms common to Muslim worship. But we were always cautious about accepting rituals whose form is inextricably linked to a heretical message. For instance, the prayer (salat) postures are filled with verses from the Qur'an. We didn't adopt this. At the same time, we used biblical forms of prayer such as kneeling, raised hands, and prostration.1

1 Phil Parshall, "How Much Muslim Context is Too Much for the Gospel?" Christianity Today, January/February 2013, Vol. 57, No. 1, 31.

A Muslim convert to Christianity may never be comfortable with things like eating pork, drinking alcohol, or, if she is a woman, revealing her hair to men. Part of the subtle nuance between displaying cultural intelligence alongside the teachings of the Bible is recognizing the difference between damaging practices and cultural preferences. Does the Bible command us to eat pork and to drink alcohol? Of course not. While the Gospel offers believers freedom to engage in such practices, it similarly encourages a spirit of gentleness for those who choose restraint, as displayed in Romans 14. It should be stressed as well that believers hailing from a Middle-Eastern culture often have much to teach believers in America regarding our lack of restraint when it comes to consumption, both materially and calorically. While there are certainly a host of negative aspects to many Middle-Eastern countries, there are numerous positives in reference to our own country which we could do well to imitate: Significantly lower rates of obesity, alcoholism, drug-addiction, pornography use, and theft, to name a few. After all, the church of God is a family, so to speak, and as a family, it requires intimate, sacrificial, and often messy togetherness. As Soong-Chan Rah says, "The church is not merely a place where we tolerate strangers; it is a place of grace and acceptance that comes from being a family."1

1 Soong-Chan Rah, Many Colors: Cultural Intelligence for a Changing Church, 176.

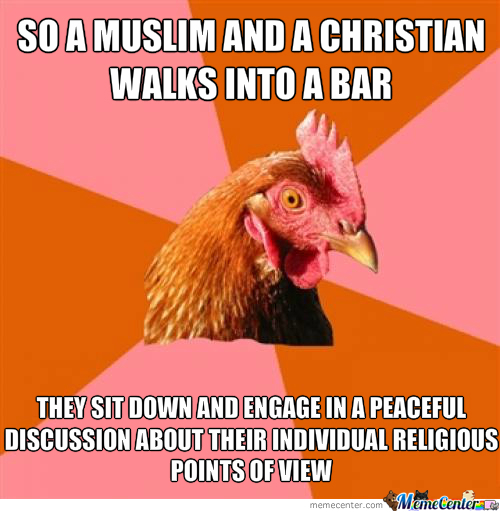

To conclude, no one culture can boast superiority over another, but we can both learn and grow through our understanding and relational engagement with each other. While the mere accommodation of different cultural perspectives may bolster the appearance of friendliness within a church, it is hardly the sort of giving of oneself that Jesus had in mind when he said, "If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. Give to the one who asks you and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you." In the article "Dates, Gatorade, and Ramadan," the author gives these items away to Muslim international students engaging in their Ramadan fast for use after sundown. His purpose was not to affirm a Muslim holiday, it was to affirm the individual who had a clear need that could be met. The author writes, "Loving one's neighbor is not about manipulation, or exploiting a person's needs to get them to convert. Hospitality expresses one's own conversion; it shows who I am in Christ."1

Cultural intelligence takes time. It is an investment in the person that goes beyond mere interest, tolerance, or accommodation, and strives to enter into a relationship of mutuality and reciprocity, into a place where we both give and receive, recognizing the talents, lessons, and insights that all cultures and paradigms can bring to the table.

1 Gordon G. Groseclose & Steven C. Hokana, "Dates, Gatorade, and Ramadan," Cultural Encounters: A Journal for the Theology of Culture, 2011, Volume 7, No. 1, 113.