Humanism and its effect on the Reform ideals of Ulrich Zwingli - Part 1

Swiss Reformation leader Ulrich Zwingli's education in humanism, resulting from the rise of Renaissance Humanism during the 16th century, was the foundation of his theological belief system and his efforts in reformation of the Holy Roman Church. Zwingli's exposure to humanistic teachings during his formative years and the influence of Renaissance humanism in society were the chief contributors to his position against what he believed to be abuses and false teaching within the Holy Roman Church and differences in the theological understandings within the Protestant Reformation movement across Europe.

To understand the nature of Ulrich Zwingli’s theological position, one has to have a basic understanding of the Renaissance period and how humanism was changing the face of not only religion, but the social and political structure of Europe. Renaissance humanism was fueled by the love of the texts of ancient Greece and Rome. This pursuit of the classics lent itself keenly to gaining a deeper knowledge of Scripture and the writings of the “Fathers” of the church such as St. Augustine.[1] The word “Renaissance” means “rebirth”, and implies the concept of renewal. This is what society was attempting to do-renew itself through a connection with the past. Historical professor, Alister McGrath, conveys this idea when he states that Renaissance humanism was best described as “a quest for cultural eloquence and excellence, rooted in the belief that the best models lay in the classic civilizations of Rome and Athens.”[2]

Ulrich Zwingli was born on January 1, 1484 in Wildhaus, which was about fifty miles south of Zurich. His father was the chief magistrate of the hamlet and his mother was the sister of a priest, John Meili who in 1487 transferred to Wesen and took young Ulrich with him, beginning Ulrich’s education.[3] In his pre-teens he studied Latin in Basel, and at fourteen entered the university in Bern under the tutelage of Heinrich Wölflin. Wölflin a teacher well-steeped in Renaissance humanism, instilled in Zwingli a love of the classics.[4]

Zwingli was a student of Conrad Celtis and studied under Celtis at one of his academies in Vienna. Celtis was a German humanist and Latin poet, who spent two years in Italy enhancing his humanistic training with the likes of Fincino and Guarino. He brought back with him the idea of beginning humanist academies in Germany.[5] From the age of sixteen to eighteen Celtis would instill his knowledge of humanism into Zwingli.

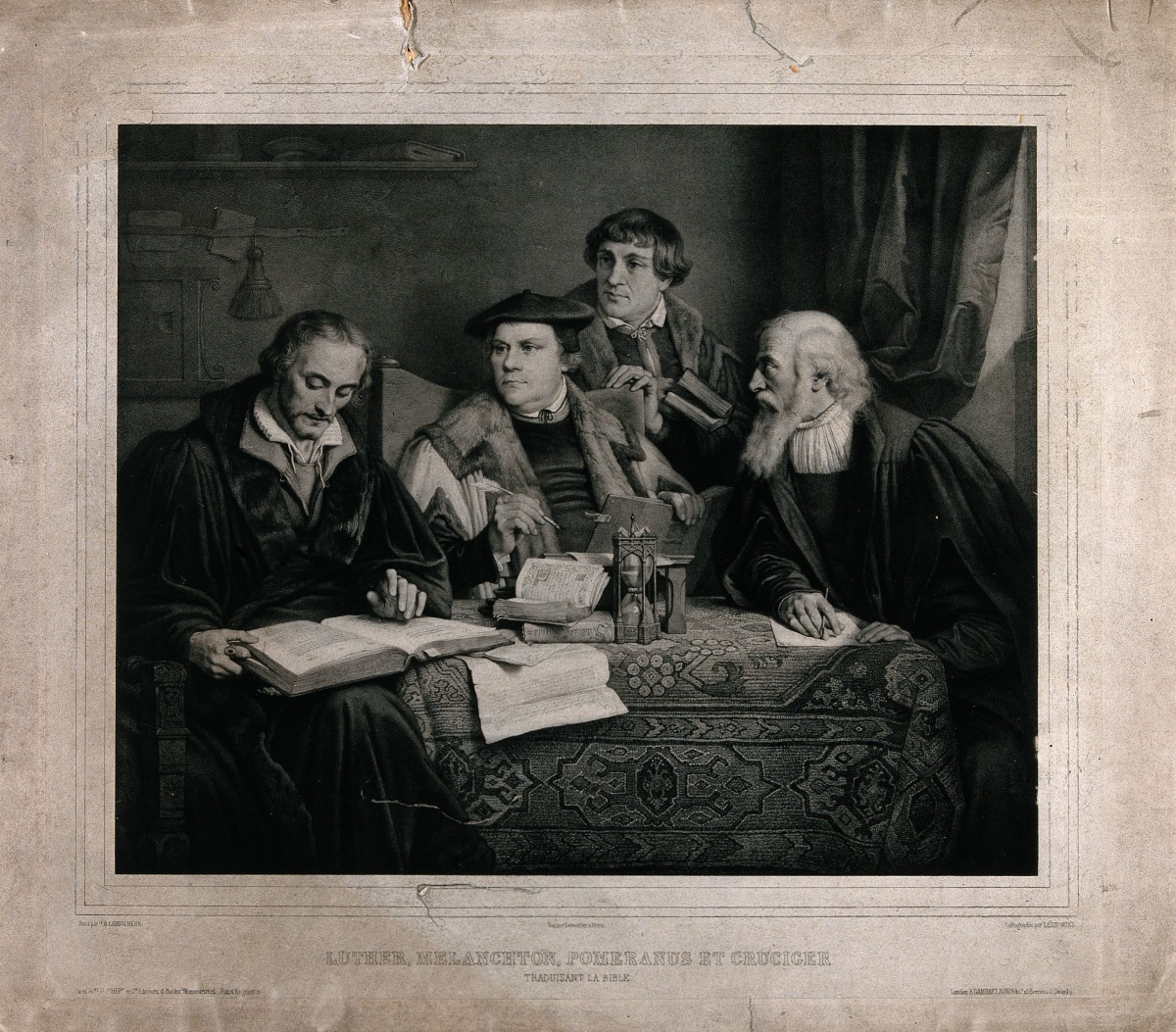

Zwingli then returned to Basel where he began to study theology under Thomas Wyttenbach, a well-known critic of scholasticism, who frequently lectured on the New Testament.[6] Through Wyttenbach, Zwingli became aware of the abuses within the church. Wyttenbach regularly criticized the Church’s practice of indulgences, the vows of clerical celibacy that were not being adhered to and the idea of transubstantiation in regards to the Eucharist.[7] These would also become major themes for Zwingli and he would address them with the likes of Martin Luther, Desiderius Erasmus and other reformers of the time. They would also be the themes for division in the various forms of Protestant reformation, especially between Zwingli and Luther.

At twenty three, Zwingli had secured his pastorate in Glarus, and in typical, humanistic fashion, taught himself Greek so that he might read the New Testament in its original form, and as Will Durant expounds,

He read with enthusiasm Homer, Pindar, Democritus, Plutarch, Cicero, Caesar, Livy, Seneca, Pliny the Younger, Tacitus … and corresponded with Pico della Mirandola and Erasmus calling Erasmus “the greatest philosopher and theologian.”[8]

Zwingli’s ties to Erasmus not only as his friend but also through his intellectual, spiritual and scholarly influence distinctly identified Zwingli with the humanistic and social ideals of Erasmus. This could be seen in his view of human reason and how he, unlike Martin Luther, was able to make logical conclusions on a topic from scripture rather than having indifference when scripture itself remained silent on the issue. His ties to Erasmus were also present in the Erasmian ideal that personal, as well as social virtue, were critical. This would be in direct opposition to Luther’s excessive insistence on justification by faith alone without works.[9]

Zwingli and the other Swiss reformers were also very attached to the nationalist agenda. This agenda held that the cultural and political renewal that was going on in their nation went hand in hand with the renewal of the faith.[10] Erasmus would write Zwingli and appeal to Zwingli’s obvious nationalistic disposition and tie in both the humanistic and nationalistic feelings. Erasmus wrote, “Hail to the Swiss people, whose character particularly pleases me, whose studies and morals you and those like you will improve!”[11] This nationalistic fervor was not just mere fancy. Zwingli would also show his nationalistic and humanistic bent in his letter “The Petition of Eleven Priests to be Allowed to Marry” in July of 1522. Zwingli, in addressing the Bishop of Constance, with the reformed ideal of clergy being allowed to marry, also states,

Our weakness must be indulged, nay, something must be ventured in this matter. O happy the invincible race of Hohenlandenberg, if you shall be the first of all the bishops in Germany to apply healing to our wounds and restore us to health![12]

In the process of using his humanistic approach of scripture to vindicate the marriage of clergy, he inserts his patriotic view when he calls the people of Hohenlandenberg “invincible.”

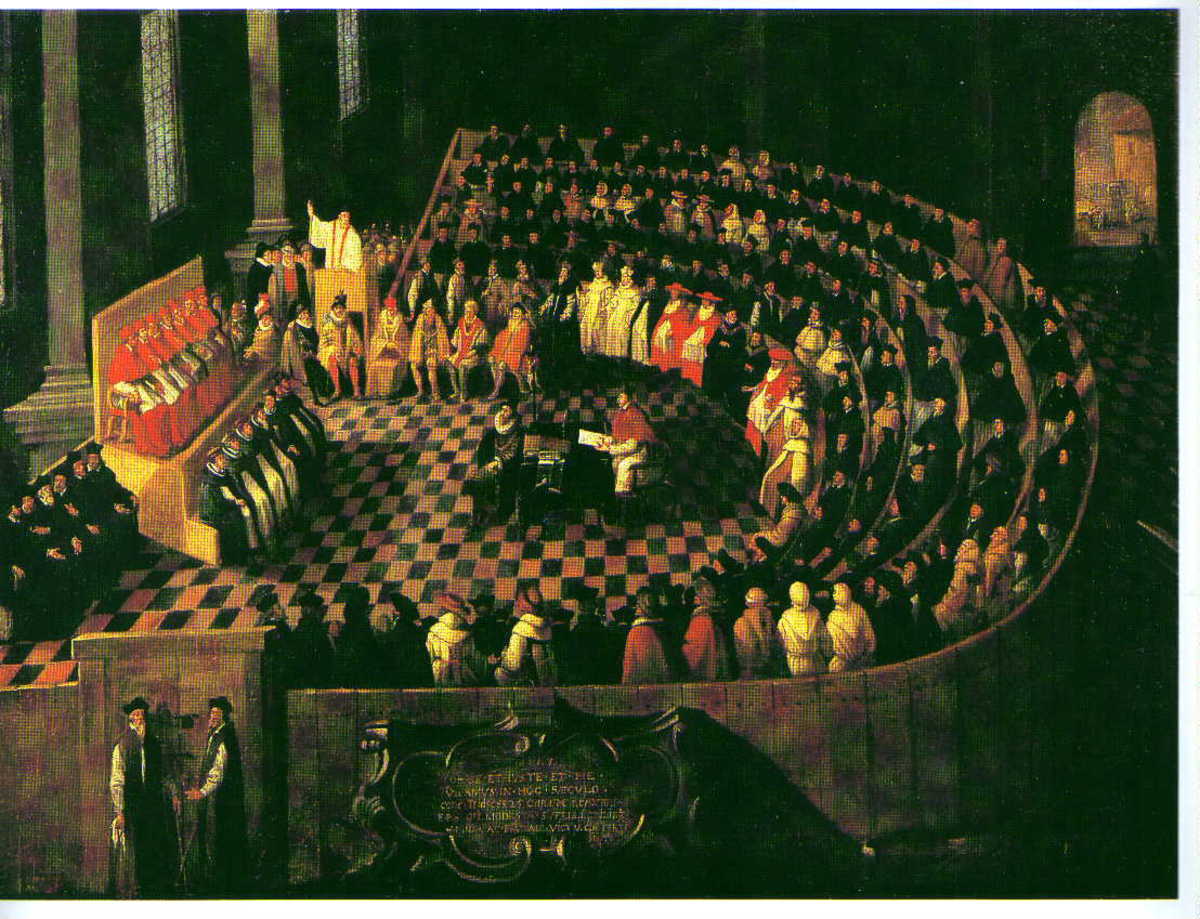

The political ramifications of the Reformation were of valid concern to the various states of Germany and the Swiss cantons. Phillip of Hesse feared theological disputes would have military and political repercussions that would lead to the disintegration of reform gains by Catholic victories on the battlefield. And he was right. Zwingli was unbending in his position that all of the Swiss cantons should reject Catholicism. However, there were many Catholic cantons who did not agree with Zwingli’s idea that rejecting Catholicism was the best idea for the nation, and they took up arms and invaded Zurich. His firm, humanistic beliefs, strong spirituality and political activism lead to Zwingli suiting up for battle as military priest and ultimately losing his life on the battlefield at Cappel.[13]

Part two will conclude the discussion on Zwingli.

Sources

[1] Mullett, Michael, Bucer, Melanchthon and Zwingli: Erasmus's Protestants (History Review, 2011), 7

[2] McGrath, Alister, Christianity's Dangerous Idea (HarperCollins, 2007) Kindle Edition, chap. 1

[3] Hottinger, Johann Jacob, The Life and Times of Ulric Zwingli (Harrisburg: Theo. F. Scheffer, 2010), Kindle Edition, chap. 1

[4] (Ibid.)

[5] Nauert, Charles G., Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 116

[6] Nystrom, Bradley P, and David P. Nystrom, The History of Christianity: An Introduction (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2004), 247

[7] Durant, Will, The Story of Civilization: the Reformation: a History of European Civilization from Wyclif to Calvin: 1300-1564 (New York, NY: Fine Communications, 1997), 404

[8] Ibid., 405

[9] Mullett, Bucer, Melanchthon and Zwingli: Erasmus's Protestants, 11

[10] McGrath, Christianity's Dangerous Idea, chap. 1

[11] Hottinger, The Life and Times of Ulric Zwingli, chap. 1

[12] Zwingli, Ulrich, Selected Works of Huldreich Zwingli (1484-1531), the Reformer of German Switzerland Vol. 1, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2012, 38

[13] Nystrom and Nystrom, The History of Christianity: An Introduction, 249