Lessons from the Salem Witch Trials

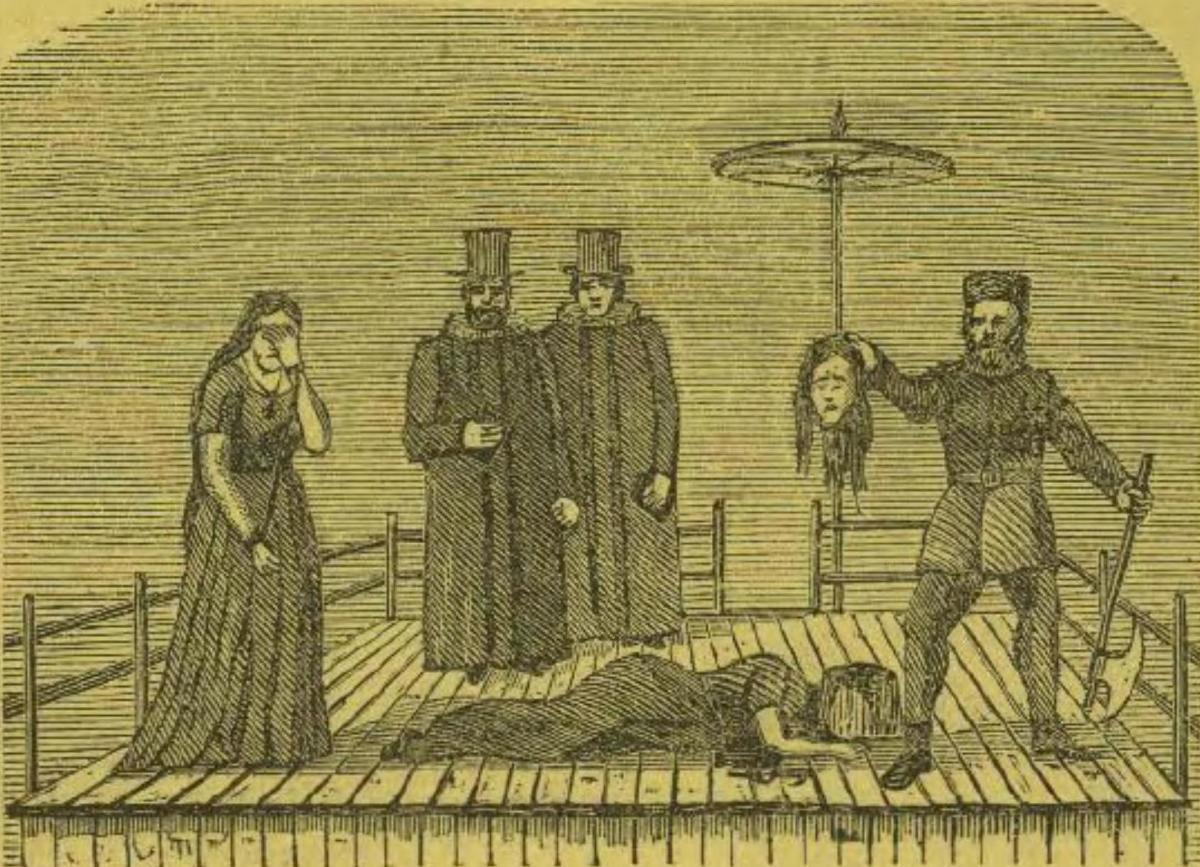

Between June and September of 1692, in Salem, Massachusetts, nineteen persons were hanged and over one-hundred fifty were sent to languish in prison. One might say that all this was caused by some silly or malevolent little girls. Alternately, one might say that the tragedy was the result of a generally prevailing stupidity and popular credulity. This latter explanation is rather comforting in this scientific age, as we may assure ourselves that we are no longer susceptible to such outbreaks of savage superstition. More accurately, however, one might attribute these events to a confluence of social forces that had long been building up to such a crescendo. Moreover, the social currents underlying these events are representative of deeply ingrained patterns of human nature that can manifest lunacy even in our postmodern world.

The Salem trials occurred in the midst of rapid social change. While Salem Village was a traditional pre-industrial society, the people there surely felt the currents of change radiating from the nearby Salem Town, a large commercial port that was creating new wealth for numerous families. In addition to this atmosphere of change, the Massachusetts colony had for years felt a certain degree of lawlessness: ever since its Royal Charter had been vacated, no officially sanctioned government would be established until William Phips was made governor.

In the midst of these already rather anomic conditions, Samuel Parris, a failed merchant, was appointed as minister in Salem Village. He began to exacerbate the already precarious fault lines in the community by painting his opponents as forces of evil in a battle of cosmic proportions. Parris seems to have had the charisma of a demagogue, as he was able to weave “the nagging fears and conflicting impulses of his hearers . . . into a pattern overwhelming in its scope” (Russell & Alexander 120). During the trials, he would say, “The Devil hath been raised among us” (Days of Judgment). Neither Parris nor the community distinguished between the personal, the political, and the religious. Indeed, a marked political pattern could be seen during the witch trials: most of the “afflicted” girls were either in Parris' household or the household of his main supporters.

So in the social environment of the Salem witch trials, all struggles were moral struggles, and moral struggles became cosmic wars between good and evil. This dynamic was further enabled by the “wonder” which pervaded the prevalent worldview at the time (Days of Judgment). Thus, while some people may not have believed in witches, the good majority probably did. The dominant worldview created a different social reality than we are accustomed to, and this social reality was populated by “historical subjectivities” (Perkins 4 – 5) different than ourselves. Both this social reality and the subjectivities that it engendered were constructed by the prevailing discursive practices of seventeenth century colonial society.

The above statement, perhaps, is one of the most important lessons we can learn from Salem. Although the enlightenment and scientific revolution have brought about Weber's “disenchantment of the world”, we are not thereby less susceptible to new madnesses and atrocities within the framework of our current paradigm. As Russell and Alexander state, “Witchcraft was not a superstition before the new world view [of rationalism] emerged in the mid-seventeenth century and . . . all world views, including scientism, breed their own superstitions” (124). The disenchanted worldview of Maoist China created its own atrocities during the Cultural Revolution. This should not be seen as an isolated incident in history, nor as a dynamic which could not possibly repeat itself in the future.

On the other side of the disenchantment/enchantment spectrum are fundamentalists of every persuasion throughout the world today. For these populations, the supernatural is still very real, and often capable of inciting myriad forms of insanity. Consider the bombing of abortion clinics by certain radical Christians, or the attacks on the World Trade Center by certain Muslim extremists. Salem is instructive for these cases as well, as they represent the fundamental inability to separate the personal, political, and moral/religious that was exemplified at Salem. The Salem Village meeting house was not only a church, but the center for civic activity and municipal politics, much like the Greek Ἀγορά (transliterated as 'agora'). This failure to separate church and state, I believe, is often central to modern fundamentalist worldviews, which, even in their vigilante forms, express a desire for theocracy.

Days of Judgment speaks of how social fears and tensions in the seventeenth century Massachusetts colony were projected onto Indians (Native Americans) and missionary Quakers, and finally onto witches. This points to the social function of scapegoating, which relieves more generalized—and thus more difficult to assuage—anxieties by providing them with a focal point that allows for directed action against the new, more tangible fear. One essential element of scapegoating is the dehumanization of the scapegoat. One must dehumanize one's opponents to truly harm them (Days of Judgment). War would not be possible if not for the many skillful means humanity has developed for the dehumanization of the “other”. Such dehumanization is simple when a group embraces a cosmic dualism between forces of good vs. those of evil. Since human beings are morally ambivalent, any purely evil being is necessarily inhuman. Thus, people have dehumanized those outside their reference groups for millennia by caricaturing them as completely evil. In the second and third centuries, Christians were widely suspected of drinking the blood of murdered infants, after which they would

“begin to burn with incestuous passions. They provoke a dog tied to the lampstand to leap and bound towards a scrap of food which they have tossed just outside the reach of his chain. By this means the light is overturned and extinguished . . . in the shameless dark with unspeakable lust they copulate in random unions. . .” (Felix Ch. 9)

Lest we think that people no longer fall for such obvious vilification campaigns, we must remember how George W. Bush continually referred to “evildoers” to justify any military action he had in mind.

Finally, Days of Judgment mentions that during the McCarthy period, many would-be critics kept silent so as not to be themselves accused of being communist subversives. Such a dynamic surly also played itself out during the Salem trials, as would-be critics feared being accused of witchcraft themselves if they spoke up. As Edmund Burke is famously misreported to have said, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” If I were in such a position myself, I certainly can't claim that I would be outspoken, risking my own life. I hope that I would, but the power of such social situations makes it impossible for me to predict my own behavior. The power of the situation, emphasized by social psychology, is the final lesson we must take from Salem.

Works Cited

Days of Judgment. Film produced by Robert Tarutis.

Felix, Minucius. "Octavius." After the New Testament: A Reader in Early Christianity. Ed. Bart D. Ehrman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Pages 54 – 57. Print.

Perkins, Judith. The Suffering Self: Pain and Narrative Representation in the Early Christian Era . New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Russell, Jeffrey, and Brooks Alexander. A History of Witchcraft. London: Thames and Hudson, 2007. Print.