Lovecraft and God

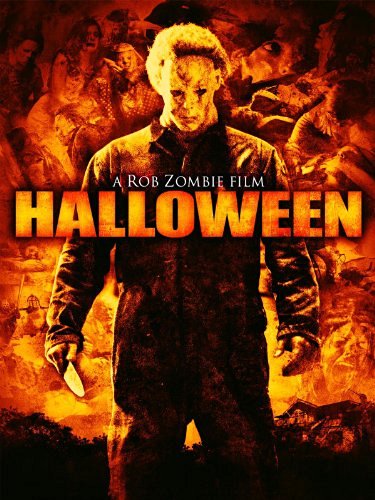

Horror picture

The Virtue of Horror

“Life is a hideous thing, and from the background behind what we know of it peer daemoniacal hints of truth which make it sometimes a thousandfold more hideous. Science, already oppressive with its shocking revelations, will perhaps be the ultimate exterminator of our human species — if separate species we be — for its reserve of unguessed horrors could never be borne by mortal brains if loosed upon the world.”

-H.P. Lovecraft, The Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family, 1925

The genre of Horror fiction thrives on despair. In the rare event that a horror story has a happy ending, it is not without great cost, whether in life, sanity or feelings of security.

What is ironic about horror fiction is that it is heavily laden with values and virtues; because without these, they could never be truly horrific.

Consider the typical slasher film: the demented killer who slays his way through a gaggle of horrified teenagers could never be terrifying if the viewers did not consider life and sanity to be virtuous and ideal – if they saw the human body as a beautiful thing in its perfect, functional state rather than as a conglomerate of mushy parts. An audience who does not hold these values will simply yawn in boredom as meaningless lives are lost at the behest of a man operating with meaningless motives who reduces mobile meat to an inert mass of moist carbon.

And yet the prospect of death – perhaps the most common condition in the universe – never fails to offer chills to the spellbound onlookers.

Horror operates by identifying core values which are common to the majority of spectators, and then mangling these values as obscenely as imagination and censorship allow. Some of the most common targets of horror fiction are the following:

Brainwashing/Possession/Insanity

Brainwashing/Possession/Insanity

Examples:

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Happening, The Exorcist

Whether in movie or book, when one encounters a human being who seems to be acting as the mindless puppet of some other force, this automatically inspires a kind of inherent fear. This could even apply to the slew of movies about demonic or spirit possession. If a friend or loved one begins to act like someone else, or opens their mouth, and the voice that comes out is that of some other creature, this isn’t just strange, it’s frightening. Even terrifying. Worse still is the threat that the viewpoint character could at any moment succumb to the loss of their own mind.

Human beings seem to value free-will: the capacity to make decisions of their own accord. The loss of this ability challenges one of the basic assumptions which people hold of their very nature. When a person rises in the morning, looks at the various outfits in the closet, and chooses one, they assume they have done so freely. More profoundly, a person lives under the impression the friends, lovers, political parties, philosophical ideas and religions they have chosen have all been chosen freely. Science and justice rest on the concept that a person is capable of weighing evidence and freely selecting that which they consider most reasonable. The brainwashed puppet of the horror movie selects (or doesn’t) not that which is best or even true. But in their mind, they are told to believe they have chosen freely and have made the right choice.

Strip a person of their free will, and you have robbed them of the most fundamental part of themselves. Or so it is assumed.

Interestingly, naturalism, which sees humans as nothing more than a brain and a body, is beginning to deny that free will actually exists at all. Human decisions come down to simple chemical and electrical activities within the brain, and as such, are purely deterministic, not free.

This as much as admits that there would have to be some kind of immaterial aspect – call it a “soul” - driving human decisions for those decisions to be free. Deny the existence of the human soul, and one seems to be as much as admitting that free will does not truly exist - the stuff of horror.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis

Examples:

Species, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Slither

The trope of a human becoming something inhuman is as old as recorded legend, and one may safely say, older than that. And it seldom is given a positive spin. When it comes right down to it, humans like being humans, and the thought of becoming anything else is frightening. This may be a simple inherent distaste everyone has for change, but it could also be a deeply held conviction everyone has that there is something sacred about being human. This is driven home by the fact that when, in a horror movie, a person sees another person – no matter how dear – transforming into something else, their first instinct is to attack or destroy this new form. The sacredness of their human nature has been violated. The person who has changed may now be perfectly happy in their new form. But their new attitude – like their new form – is abominable.

It is interesting that this deeply seated horror related to human metamorphosis works against the overall idea of evolution. At best (based on this attitude), humans are the apex of evolutionary form, and any change they may endure violates that superiority. However this idea that human metamorphosis is somehow abominable – that the human form is sacred – aligns quite nicely with the idea that humans are “made in the image of God,” are special creations made to have a relationship with their Creator, are unlike any other animal life form, and truly are sacred.

Reality is an Illusion

Reality is an Illusion

Examples:

In the Mouth of Madness, The Cabin in the Woods, Identity

The character waking up at the end of the film to discover that it has all been a dream, or that they are insane, or in a computer program, etc. is more of a last minute plot twist than it is an overarching theme. Still, it is mind-blowing enough to still be used liberally in films from The Twilight Zone forward. Humans need reality to be intelligible and ordered. Moreover, humans value truth almost more than they value anything else. If they did not, there would be no arguments about government, religion, philosophy or scientific theory. One argues because one assumes that there is a true position, and that those who do not see this truth are better off corrected than in error. Everyone has experienced at some point in their life the dawning realization that something they held to be true was wrong, and the deep disappointment that comes with that feeling.

But in order for reality to be intelligible, for one to trust one’s ability to be able to sort through facts and discover truth, one must embrace a concept of truth which is concrete and transcendent. There must be some kind of foundation for truth, intelligence, and rationality – some ultimate standard to which one can appeal.

Again, if human beings and the reality they inhabit are all products of mindless chance, then not only are they ultimately rooted in mindlessness, but there is not ultimate truth. Reality is pointless and purposeless.

Intelligent without Morality

Encounters with intelligence absent morality

Examples:

This is a theme most common with movies about psychos, ghosts, demons, robots and alien monsters. One encounters a person, creature or entity which can think and act intelligently, but cannot be reasoned with. The characters in the film have no hope of appealing to its sympathies, instructing it of the human rights it is violating in its actions, or causing it guilt or regret. In the end, all they can do is fight or flee.

The moral (pardon the pun) is simple: intelligence at a self-aware, analytical, human level is a horrible thing if not also paired with the capacity for empathy and courtesy towards others.

Of course if viewed from the perspective of naturalism, morality is simply a bi-product of human evolution, something that accompanied the rise of human intelligence. However film-makers and film-goers alike can easily imagine humans and other creatures who can act intelligently without acting morally. Moreover, here in the land of reality, there are actual people – psychopaths and sociopaths – who lack the basic ability to sympathize with others or experience guilt for immoral actions. The worst of these, the ones who actually do become serial killers, sometimes have their exploits immortalized in “based-on-an-actual-event” horror films.

Intelligence could arise, and, in fact, societies could function, without morality (ala bee hives), but intelligence is something which, when absent from morality, seems monstrous. Religions and governments around the world are founded on the principle that there is some higher moral standard to which human behavior ought to be held, and that human behavior often falls short of this standard (hence the justice system). This placing of morality on a pedestal which rises above both government and religion, towards which all people strain, seems to run counter to any idea that this immaterial, transcendent standard humans hold so high is a mere evolutionary illusion. That is a horror story.

Death

Death

Examples:

Every Horror Film Ever.

When it comes right down to it, everyone in the audience is scared that the characters in the film might suffer, go insane, be brainwashed, transform into something horrifying, or discover they are a brain in a vat, but the thing that most frightens them is that the characters are going to die. So long as they are alive, there is still a chance for redemption, but once they die, all chances are gone, the curtain falls, and the worst possible consequence has been realized.

Death is the greatest threat and the ultimate payoff. The curtain is pulled back and a dead body is shown, and the people scream and weep. A killer – natural or supernatural – stalks the victims and the tension is at its highest. There is no greater consequence, nothing more horrifying, than the threat of death; and it never loses its potency.

What is truly odd about this is that, of all of the potential threats seen in a horror movie: ghosts and monsters, insanity and psycho stalkers – death is the only one that all people will actually face.

Perhaps this is what makes it so real and horrifying. One can, to some degree, laugh off the grinning, knife-wielding doll, knowing that such things are pure fiction – but there is nothing fictional about death, and it’s that which makes an audience cringe.

Fearing death is something which may be easily explainable in a basic, evolutionary level. One wishes to avoid death because it is adaptive to do so. To a degree. But immortality, which seems to be what humans actually crave, isn’t particularly adaptive. The desire for immortality may be seen by that other horror trope: the vampire film. Vampires have gone from being horrifying to attractive, largely because they get to live eternally. In the animal kingdom, it is seen and understood that life is good long enough to bear children and raise them to maturity. After that, the creature in question is just taking up space.

But human life, as mentioned before, is seen as sacred, and death itself is seen as the enemy. This ties in quite nicely to the religious theme of eternal life.

Lovecraft and Cosmic Horror

Lovecraft and Cosmic Horror

That which horrifies people is often that which runs counter to their basic moral and philosophical convictions. It may be possible to explain fear on a biological level without religious or philosophical reasoning. However, the question becomes, is there more to human nature than mere meat, bone and blood?

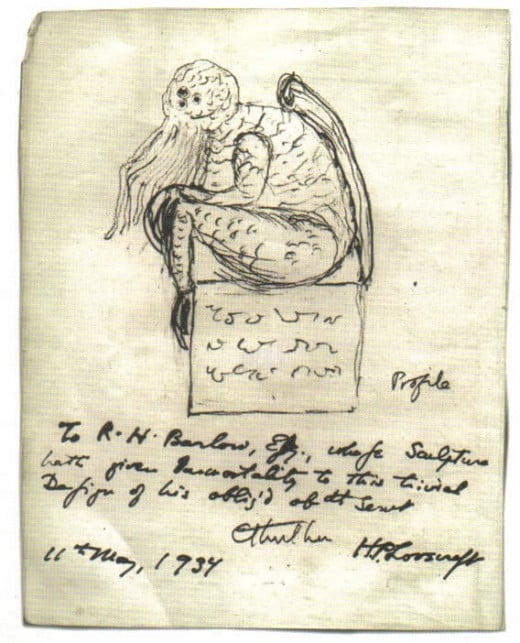

One Horror author recognized this tension more than most others: a man by the name of Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

Lovecraft was an author of “weird fiction” in the early 20th century. He was one of those penniless writers who died with little recognition, only to have his works become legendary after his death. Lovecraft was the inventor of what has been termed “Cosmic Horror,” that is, horror that capitalizes on the notion that sanity, morality, intelligibility and all other transcendent values which hold together human society are but an illusory bubble in a universe governed by amoral chaos. Lovecraft described his philosophy like this:

“…all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.... To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.”

For Lovecraft, the “big reveal” of his stories involved the protagonist discovering the horrible truth that the reality in which they had comfortably ensconced themselves was but an illusion, the loss of which led to madness – because the fragile human mind could not endure the true nature of the universe. Lovecraft expressed this idea in the prefix to his most renowned story:

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

The Development of "Cosmic Horror"

The Development of "Cosmic Horror"

In all likelihood, Lovecraft was an atheist in his beliefs. At the very least, he was no friend of organized religion. His feelings toward the religious were unsympathetic:

“Bunch together a group of people deliberately chosen for strong religious feelings, and you have a practical guarantee of dark morbidities expressed in crime, perversion, and insanity.” (H.P. Lovecraft, from his personal letters)

And he did little to hide his skepticism of religion:

“If religion were true, its followers would not try to bludgeon their young into an artificial conformity; but would merely insist on their unbending quest for truth, irrespective of artificial backgrounds or practical consequences.” (H.P. Lovecraft, from his personal letters)

Despite all the anti-religious bluster of his personal correspondence, Lovecraft had distinctly pagan sympathies, probably born out of the popularity of Romantic literature in the 19th century. The shadow of paganism was cast over his entire body of works to one degree or another. Some of his stories directly reference paganism. In his story The Tree (1920), Lovecraft writes of a rivalry between two sculptors of Roman gods. At other times, Lovecraft implicitly references paganism. The Temple (1920), for instance, tells the story of a German U-Boat which becomes the victim of a sea-curse connected to the discovery of the carved head of a statue which, in description, strongly resembles an ancient Greek god. One element of the curse has the ship being followed incessantly by a pod of dolphins – which in Greek Mythology are associated with Delphin, servant of the sea god Poseidon. The final act of the story has the last crew of the U-Boat on the sea-bottom, horror-struck by an Atlantis-like ruin, and the unknown entity which lurks within; an entity which calls to the crew in a way that strongly resembles the Sirens of The Odyssey.

In stories like these, Lovecraft does not so much deny the existence of the transcendent, but rather subverts a modern, scientific understanding of the universe by suggesting that pagan gods and magic still lurk in the hidden recesses of the world. This is especially evident in The Temple, since the protagonist of that story is a German Naval Officer and staunch Modernist who denies the supernatural nature of the crew’s experience until the bitter end when he, too, becomes victim to the siren song of madness.

In this sense, Lovecraft established two shells of reality: the world as science now understands it which rests within the larger shell of a horrifying universe governed by magic forces.

However, as his writing career progressed, Lovecraft gradually traded the magic and fantasy of a pagan universe with the chaos and mind-boggling forces of a science fiction universe. This transition may be seen in two distinct stories which form mirror opposites. The Strange High House in the Mist (1927) tells the tale of a mysterious house which has stood over a sea cliff for ages eternal. The protagonist finds a way into the strange house and meets the strange old man who lives there. They then go through an experience wherein some force assaults the house, attempting to gain entry to the door which withstands the terrible and horrific battering. Thereafter another knock comes at the door which the old man opens. This time the house is visited by a veritable pantheon of rollicking gods, nymphs, dryads and other mythological characters, and everyone has a good time.

The mirror opposite of The Strange High House in the Mist is a story titled The Other Gods (1921). In this story, two priests ascend a peak which promises to give them a glimpse of their pagan deities. When one of the priests stands at the brink and looks into the face of the gods, he is horrified to discover that the pagan gods he worships are mere puppets of incomprehensible “Outer Gods,” terrifying beings of chaos which are the true masters of reality. The “Outer Gods” of this story are likely the forces which assaults the Strange High House at first, which the house’s owner was wise enough to not allow entry.

In these stories, Lovecraft gives his audience a third shell to reality. There is the world understood by modern science, which rests in the shell of magic and fantasy, which in turn rests in the shell of vast, incomprehensible cosmic forces. It is these forces which eventually provided the material for his horror legacy.

Once Lovecraft had transitioned from Fantasy-Horror to Science-Fiction-Horror, he composed some of his most well-loved tales, often fusing the elements of Fantasy with Science Fiction. Consider, for example, one of his most famous inventions: The Necronomicon. This fictitious “book of the dead” is purposed in some of his stories as a grimoire of dark magic, while in others, it is a guidebook to the prehistoric monsters and aliens that lived on the churning and ugly primitive earth before humans ever existed; and also a reference book about the chaotic cosmic entities which formed and control the universe in dimensions beyond our own.

In two of his most famous stories, Lovecraft takes the story frame of his previous tale, The Temple, and modifies it for his new genre of Cosmic Horror. In one story, he tells the tale of a castaway lost at sea who finds himself stranded on a geological upheaval, which lifts a vast section of the sea floor directly below his lifeboat. As the castaway explores his new surroundings, he is horrified to find an enormous submarine monster in the act of worshiping his primitive gods.

This story, named Dagon, references an ancient Sumerian god of the sea, implicitly suggesting that early cultures worshiped these monsters, who, in turn, worship their own gods. Lovecraft later fleshes out the gods being worshiped by the sea creatures as even more monstrous beings from other dimensions. The most famous of Lovecraft’s interdimensional “gods” is the alien creature named Cthulhu, who lies in stasis in his alien temple beneath the ocean. Lovecraft describes Cthulhu as a high priest of the Great Old Ones, signifying that, even as humans worship Cthulhu, he worships something even greater than himself.

The significance of God vs. Cthulhu

The significance of God vs. Cthulhu

One of the more persuasive arguments for the existence of God is the existence of objective, immaterial, transcendent concepts. These include things such as logic, reason, morality, math, etc. If it can be proved that these things actually exist external to humans, and are not mere byproducts of the human mind, then there must be a singular, transcendent, immaterial intelligence that unifies these things in its being.

Lovecraft’s cosmology flips this concept on its head by introducing cosmic, immaterial beings which countermand morality, logic, et al. In Lovecraft’s universe, concepts such as these are mere whims of the human mind, and the actual universe may only be accessed by someone who has broken this illusion by revoked order, morality, logic and so forth. This person, now “insane” by the standard of reasonable people, is able to see the truth about the chaos which forms reality.

This is highlighted by this quote from Call of Cthulhu:

“The time would be easy to know, for then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom.”

Ironically, if one truly attempts to think through Lovecraft’s cosmology, it becomes clear that his chaotic universe is impossible. Reality MUST be governed by laws, order and intelligibility. Take, for instance, Lovecraft’s chaotic beings.

Lovecraft had a true talent when it came to envisioning alien creatures. While most science fiction writers resort to making their aliens essentially humans in green makeup, Lovecraft’s beings were really and truly alien. He described fungoid creatures with solar sails for wings whose upper body was festooned with pincers and graspers and biological tools of all varieties. He introduced a creature with hexagonal symmetry and bizarre wings and tentacles and no actual head. He spoke of beings made of cones of flesh with various sensory and communicative organs protruding from its top.

But despite their bizarre appearances, the aliens of Lovecraft’s stories build civilizations, pursue science, communicate with one another, and seek knowledge, truth and freedom.

Likewise, the alien gods of Lovecraft may be monstrous and chaotic, however, they exist and have agency and intention. The very fact that they are distinct and nameable entities – that something can be said as to their nature and existence – implies that there are laws and order that drive and sustain them.

The fact of the matter is that no one can envision and define pure chaos, because such a thing cannot exist. The further one dismantles law, reason and order, the closer that person gets to pure nothingness. For something to exist is for it to have order. The mere fact that the horror author must use words in order to communicate concepts to the reader binds them to the laws of intelligibility.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Nothing better highlights the orderly nature of the universe than trying to envision a universe governed by chaos. In point of fact, if a person can envision something with their intelligence and reason, that thing is not chaotic. What people call “chaos” is, at best, a lower state of order, but one which is governed and expressed by intelligible laws. The very fact that archeologists are able to glean treasure troves of data from a few shards of ancient pottery, or that paleontologists can reconstruct some ancient beast from a fragment of its fossilized skull, or that the fire marshal can inspect the burnt-out husk of a decimated building and determine the cause of the fire, or that a detective can inspect a ripped up crime scene and reconstruct the crime, or that an astronomer may gaze at a cloud of gas and tell the entire history of the star that formed it – these things speak of the order and governance of an intelligible universe, even when time, decay and entropy have their way.

For the universe to be ordered and governed and intelligible and lawful strongly hints that there is an orderer, governor, intelligence and law-giver operating behind it. It is impossible for there not to be.