Preaching That Disturbs The Sleepers

Are Preachers Rousing The Sleepers?

This train don’t pull no sleepers, this train!

This train don’t pull no sleepers, this train!

This train don’t pull no sleepers,

don’t pull nothing but the righteous people.

This train don’t pull no sleepers, this train! (Traditional Negro Spiritual)

These words came to mind as I read John W. Wright’s Telling God’s Story and Charles L. Campbell’s The Word Before The Powers. There are sleepers sitting in the church pews every Sunday. The question is: what are preachers doing to wake them? Are most preachers content to perform the “congregational-centered preaching” criticized by Campbell (Campbell 68)? The “comedic hermeneutic of preaching” which Wright reprehends is certainly more palatable than other approaches (Wright 38). While Campbell and Wright use very different language in their discussions of preaching, both share useful considerations for those seeking a better understanding of what constitutes ethical, productive preaching--- preaching that wakes the sleepers.

The task of this article is to offer a critical analysis and comparison of the aforementioned works by John W. Wright and Charles L. Campbell. Both writers present convincing arguments for a preaching that pushes the listener beyond their comfort zone. Campbell presents a compelling argument about the “powers” that cannot be ignored, while Wright, with equal fervor, calls preachers to a higher standard of preaching through the use of the narrative. As a framework for this analysis, I have chosen the notion of congregants as sleepers who must be aroused from a deep sleep. It is within this framework that one can readily see the consequence of a more ethical standard in preaching, a standard necessary if the Kingdom is to be realized and if the “sleepers” are ever going to become the “righteous people.”

Wright's use of the narrative

Wright sees narrative as imperative in forming a righteous people or a “contrast society” (Wright 38). Every person has a narrative of their own and most Christians are familiar with the Biblical narrative. Wright suggests that a preacher must not be tempted to help listeners feel comfortable with their own narrative, but rather, the preacher must push listeners to a point of discomfort. This is accomplished by moving from a comedic hermeneutical moment to a tragic or negative hermeneutical moment (43). The comedic hermeneutical moment allows individuals, or interpreters, to find affirmation rather than disturbance. Although there is the advantage of relevancy, in regard to the text, an interpreter’s core narrative is never challenged (38). Unfortunately, this narrative is often shaped by society rather than God’s active narrative in society.

Wright clearly expresses the need for God’s story to supersede the individual story. He states that the tragic hermeneutic provides the opportunity for the “incorporation of human life within the biblical narrative of God’s redemption of all creation through Jesus Christ” (43). According to Luke 12:51, Christ did not come to bring peace, but division. This is radically different from the “fusion of horizons” that Wright states is the result of some preaching (34). Wright believes the use of narrative is essential in preaching, but the story must push people to their critical selves. Wright’s emphasis on the use of narrative, particularly the use of the Biblical narrative, is similar to the importance that Charles Campbell places on the Biblical story. However, Campbell has a particular goal in the use of the narrative----to preach against the powers that have been revealed to us in Scripture.

Campbell fights the 'powers'

Campbell offers a stirring account of a congregation in southern France committed to resisting the violence of the Nazis by providing “sanctuary to over five thousand Jews” during World War II (Campbell 1). This congregation had been moved by the Biblical narrative to become disciples, active in the world and resisting the powers. Their pastor had successfully preached the narrative as to convict and convert his congregants so that they were prepared to bear their cross when the time came. This community of faith in southern France was fully awake.

Although Campbell spends considerable time exposing the powers, basing much of his ‘power-talk’ on Ephesians 6:12, he uses this discussion to suggest an ethic of preaching that empowers congregants to be able to resist the powers. Campbell defines ‘powers’ as systems. Because systems often become corrupt and oppressive, it is necessary to stand against them. Preaching should move people, wake people and push people to stand. Ethical preaching moves people toward righteousness, and to a level of discipleship that allows them to do the right thing even when it costs something. Preaching, like Scripture, must be useful (Wright 15). It seems that this is the crucial connect between Wright and Campbell---preaching is ethical when it moves people to take up their cross. Furthermore, this is not an individual effort; both authors see the value in community.

This “participation in an adventure called the Kingdom” and “shift of allegiances from those of society at large to those of the church” is a submission to Christ and a visible, active move to stand against the powers (Wright 44). In other words, legitimate Christians must create an alliance with Christ and his work against the powers. Campbell reminds preachers that they must attend to communal practices that nurture resistance, as well. He states that discipleship is “not a matter of a new or changed self-understanding, but rather to become part of a different community with a different set of practices” (Campbell129).

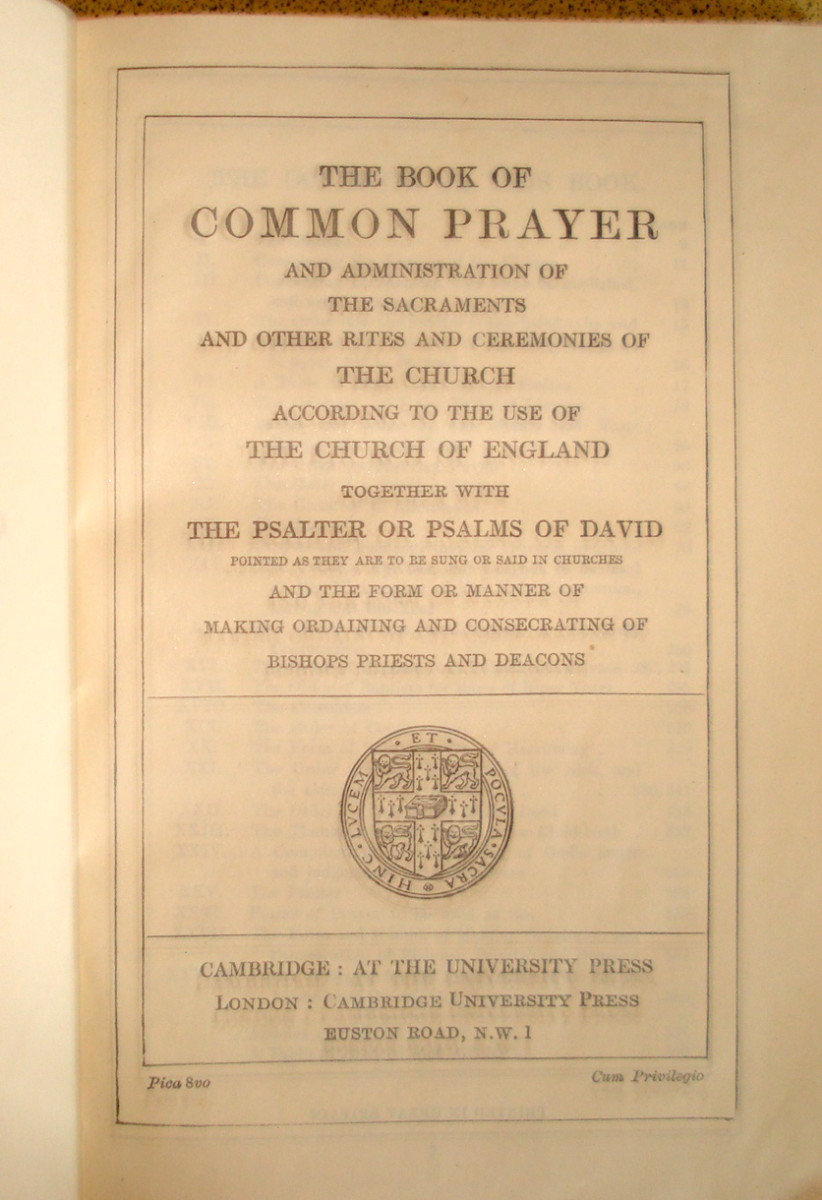

One of the many useful tools available for preachers

Ethical, Kingdom-minded sermons

As a preacher, I found both authors inspiring and helpful in their thorough offerings. Wright and Campbell adequately present options for ethical preaching while retaining the idea that Christianity is communal. Wright is Kingdom-minded as he discusses preaching that moves beyond individual therapy to an honest telling of God’s redemptive story in the world, a story that reflects the life of the faith community. Campbell convincingly argues that ethical preaching is preaching that exposes the powers and principalities that threaten to destroy humanity. In addition, he reminds readers that preachers committed to ethical preaching must also be committed to nurturing a community of disciples who are equipped to stand against the powers.

Armed with the ideas put forth by Wright and Campbell, I am better equipped to disciple people. Not only are sermons useful for pushing laypeople out of their comfort zones, but a good sermon convicts those delivering it, as well. Although I have always agreed with Martin Luther’s thought that preaching is a most difficult occupation (Campbell 69), these books have reminded me of just how daunting the task really is. The task itself requires that one places oneself at odds against the ‘powers’ that Campbell speaks about. Preparing a sermon that will move people into action and equip Christians for battle is a challenge. All too often, pastors are attempting to speak to the personal needs of individuals, rather than speaking to the body of believers.

Wake up! Sleepers!

Preachers have to be awake!

Today, churches are full of sleepers. Everyone seems to be along for the ride. If a prayer is ‘answered,’ that is a “blessing” and church must be working. Church has become a gathering place for folks who hold a ritual practice in common. Oftentimes, the ritual is founded on beliefs that have very little to do with God and Scripture. Utilizing the tragic moment to teach resistance of the powers is an approach that wakes the sleepers and gets them working. The powers continuously attempt to subvert the justice and righteousness of God. The community of faith has been set apart to stand against the powers. Ethical preaching presented in a convicting narrative form is necessary if ‘this train’ is ever to reach its destination.

This train is bound for glory, this train!

This train is bound for glory, this train!

This train is bound for glory, if you ride it you must be holy

This train is bound for glory, this train!

---Traditional Negro Spiritual