The Book of Revelation Lives On

Link to Fresh Air Interview of Elaine Pagels

- Book Of Revelation: 'Visions, Prophecy And Politics' : NPR

Princeton religious scholar Elaine Pagels puts the tales of death and destruction from the New Testament's final book into historical context in Revelations: Visions, Prophecy and Politics in the Book of Revelation.

Was John Simply Wrong?

In her new book, “Revelations: Visions, Prophecy and Politics in the Book of Revelation”, Elaine Pagels presents what is in my mind the only plausible interpretation of the Book of Revelation. Instead of reading it as a description of the literal, apocalyptic events to take place in the imminent “end times”, she describes the book in the context of its author’s times. In other words, she uses the approach generally used for all historically significant books.

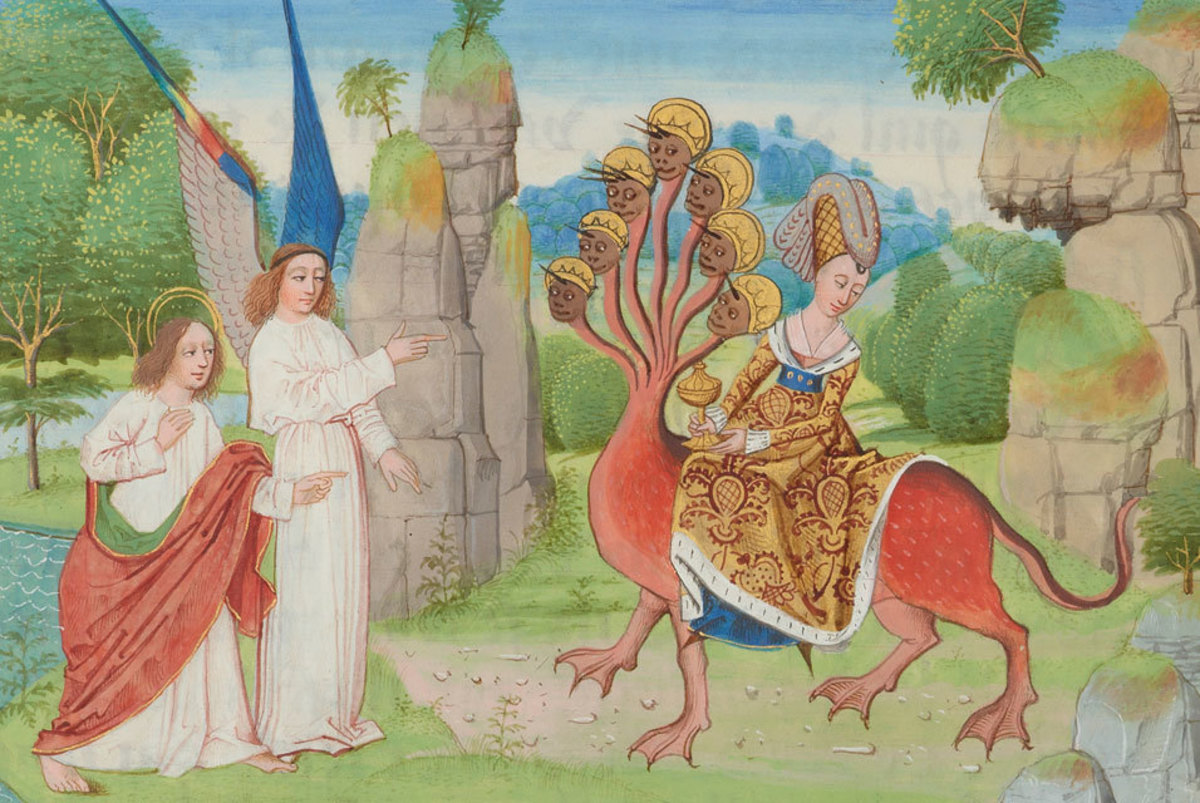

The Book of Revelation is filled with vivid, terrifying images of monsters, epic battles, and hordes of dead bodies. But in the late 1st century, the time period that most scholars believe its author (John) lived, these images would have easily been understood by his contemporaries as references to the Roman Empire. And in John’s mind, the end of Rome and the glorious return of Jesus were imminent. The Romans, after all, had not only crucified the promised Messiah roughly sixty years before. They had also recently crushed a Jewish rebellion and leveled the Jewish temple. Actions such as these were not only signs of Jesus’ promised return. They also merited the wrath of God that would come raining down on this idolatrous, evil empire that had consistently persecuted His people. The recent eruption of Mount Vesuvius and its burial of the city of Pompeii may have provided one more sign - along with some of Revelation’s violent imagery - of the battle of Armageddon to come.

The only problem with this interpretation, of course, is that the Roman Empire was not destroyed through the glorious return of Jesus. Instead, it would endure for centuries, and in the fourth century, it had become a Christian empire. In the end, the Roman Empire arguably did more to promote and spread the Christian faith than any civilization before or since. And when the Western Roman Empire did finally fall, it was after decades of gradual deterioration rather than a dramatic, apocalyptic event. Christians, rather than celebrating the fall of the “whore of Babylon”, generally viewed this as a step backward for civilization, wary about a future of potential political chaos and kingdoms ruled by barbarian invaders. Meanwhile, the Byzantine Empire would survive for another thousand years, and the legacy of Rome would live on through the structure, language, and seat of authority of the Roman Catholic Church.

So if John was wrong, there were only two things that could be done. The Book of Revelation could have been recognized as mistaken prophecy and never included in the Biblical canon. Or the powerful imagery could be reinterpreted by each succeeding generation, with people viewing the events of their time as the prophesied great struggle between good and evil. Each generation, after all, tends to view contemporary events and struggles as uniquely epic and important, and we tend to forget that past generations felt the same way. There is also a natural tendency to believe that the world is in a constant state of deterioration, an instinctive impulse to preserve our society’s cultural heritage in the face of inevitable change. And as the centuries passed, people became increasingly less aware of how Revelation’s imagery would have been interpreted by people of the 1st century.

Today, Christianity in America is alive and well, and so is Biblical and historical illiteracy. Since few people read the Old Testament, they fail to understand Revelation’s references to Jewish stories and prophecies that John (and his target audience) would know well. And because few Americans know much of anything about events 2,000 years ago, they fail to grasp the traumatic events of John’s time. It’s easy, therefore, for people to buy into the interpretations of the preacher or denomination of their choice, susceptible to that natural human impulse to believe that John must have been talking about us. Our experiences, after all, are unique, and the major events of our time must be signs that the end is near. It is comforting to believe, after all, that Jesus will come back soon and save us the trouble of confronting our complex problems.

And so the Book of Revelation lives on, and centuries of failed interpretations predicting the imminent end times have done little to hurt its reputation. This is partly the result of its author’s ability to create powerful, enduring, adaptable images that can be easily applied to virtually any circumstances. But it is also a result of our human desire to find order in the chaos and to believe that the injustices of our time will soon be made right. Every generation believes that there are contemporary circumstances that God cannot tolerate for long. And every generation seems to forget very easily the previous generation’s incompetent prophets, and people fail to ask themselves why a world in a constant state of deterioration has managed to endure for so long. Or maybe they think that someone in our generation will finally plug the correct people and events into Revelation’s secret code, and we will finally be ready for those “end times.”

Check out my new book

I recently published a collection of essays related to American History. The link below will take you to a hub that provides more details, including links to where it can be purchased.