The Guiding Question of Dasein

Da-sein is a being which is related understandingly

in its being toward that Being. In saying this we are calling

attention to the formal concept of existence. Dasein exists.

Furthermore, Da-sein is a being which I myself always am.

-Martin Heidegger, Being and Time[1]

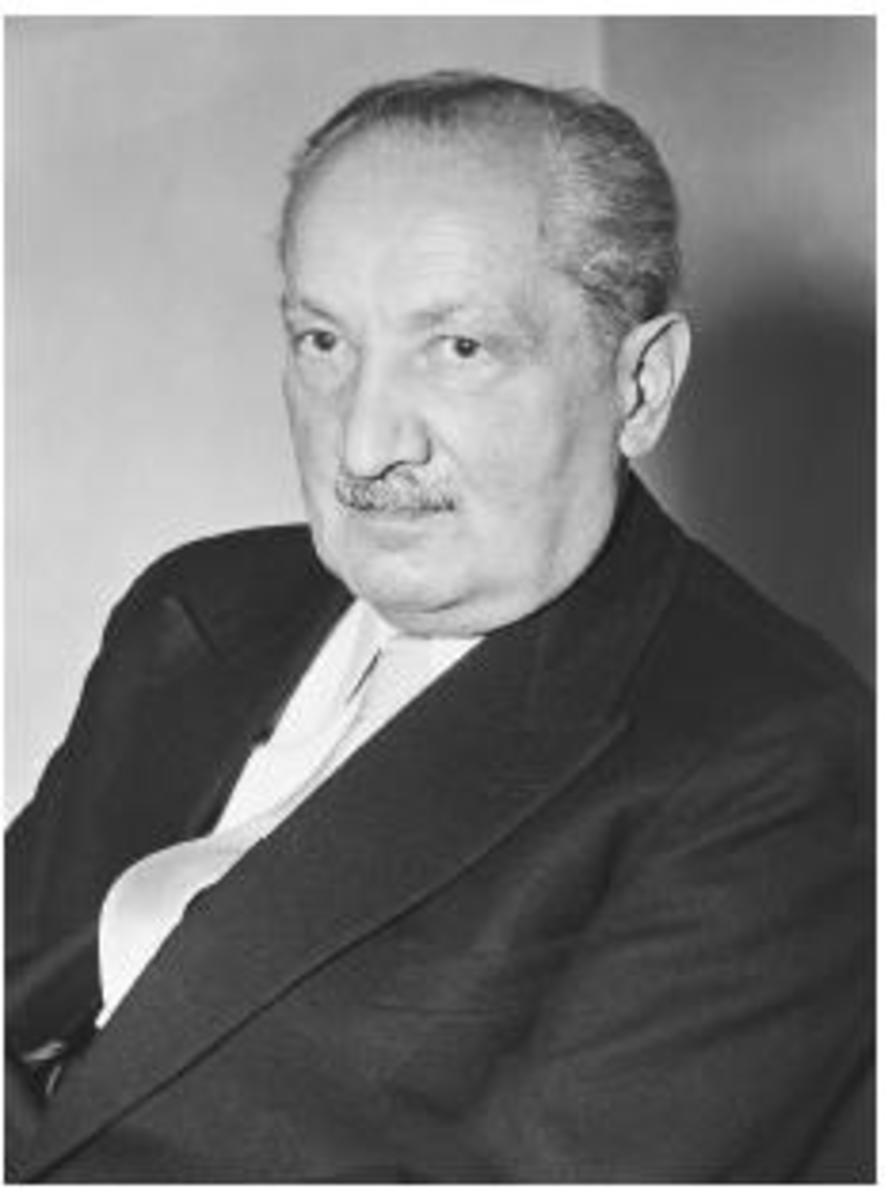

Martin Heidegger was born in Messkirch, Germany, on September 26, 1889. In year 1909, he spent two weeks with the Jesuits as a seminarian, but later on he left due to health reasons; afterwards he studied theology at the University of Freiburg. Years after, in 1911, he switched his course to philosophy.[2]

Heidegger’s philosophical development began when he read Brentano, Aristotle, and the latter’s medieval scholastic interpreters. The demand of Aristotle in Metaphysics, to know what it is that unites all possible modes of Being, indeed became the question that ignited Heidegger’s philosophy. From this orientation, he began to engage with Kant, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche in the 1920s, and later on with Husserlian phenomenology, in which Heidegger was influenced in developing his own brand of phenomenology. Out of the different influences, explorations and critical engagements, Heidegger’s greatest work, Being and Time (Sein and Zeit), was born.[3] It primarily deals with the question of the meaning of Being, and also discusses his concept of Dasein.

Martin Heidegger emphasizes in his book, What is Philosophy?, the importance of the question of Being in the area of philosophy as its starting point. He states that one is philosophizing when one is focused in understanding the meaning of Being.[4] This also indicates the kind of approach Heidegger takes in philosophy – ontology. He continues in explaining that the question, “what is the meaning of Being?” is already discussed by some philosophers in ancient times, although not thoroughly. According to him, Aristotle endeavors to answer the question: what is the meaning of the Being of being?[5] For Aristotle, the Being of being rests on its Beingness (ousia) which he calls as energia (actuality), while Plato calls this as idea.[6] In Being and Time, Heidegger claims that the meaning of Being that is endeavored to be explicated by ancient philosophers like Plato and Aristotle is distorted through time by different individuals until the time of Hegel’s Logic.[7] The general understanding now about the meaning of Being is simplified by different prejudices such as the most universal concept, indefinable, and self-evident; hence there is no need for further explications. Because of this, Heidegger calls for the retrieval of the question concerning the meaning of Being.[8] However, in Heidegger’s attempt to scrutinize the answer of the question, it seems that he was reaching into a void, or rather, the meaning of being appears to be undiscoverable. He said, “the question itself is obscure and without direction”.[9] But for Heidegger, the question must be addressed, since understanding Being is the beginning of philosophical ideas. Besides, we encounter beings in our everyday activities like in playing basketball, eating snacks and the like, yet we are not aware of the meaning. The issue of Being must be apparent. Now instead of answering the question, Heidegger turns his focus to formulating a structure of the question of Being in a way that will lead us to a better understanding about its meaning. As he said:

The question of the meaning of Being must be formulated. If it is – or even the – fundamental question, such questioning needs the suitable transparency. Thus we must briefly discuss what belongs to a question in general in order to be able to make clear that the question of being as an eminent one.[10]

In formulating the structure of the question of Being, Heidegger affirms first that the meaning of Being is available to be asked. According to Richard Polt, Heidegger recognizes that before we can ask the question of Being; it follows that we must have some familiarity about the issue of the question which is Being.[11] This means that before we can ask a question, we should have a background, or a minute understanding about the question. For how can anyone ask a question if he or she knows nothing about the subject matter of the question? Johnson gives the following example to illustrate the concept:

A friend makes you the best cookies you have ever tasted. They taste so good that you want to be able to make those cookies by yourself. This is what you want to know. So you ask your friend for a recipe. The cookies are what you ask about, and you ask the question because you already have a grasp of the cookies.[12]

In the idea of familiarity, we are able to ask questions because we recognize the issue of the question. An individual may be able to ask the recipe of a friend’s cookie because he or she is familiar with its taste. It is the same way in scrutinizing the meaning of Being. Since we are able to ask about the meaning of Being, it means that Being is familiar to us in some way.

However, Being is very broad and complex idea that we can refer to existence. We can only inquire the meaning of Being by addressing the question to ourselves. Besides, we cannot ask the meaning of Being to a cookie, tree, or stone because these kinds of being do not have the capability to understand Being, but we human beings are able to know and understand the meaning of Being as we understand other kinds of being such as a cookie, tree or stone.

It is said that if we are going to ask for the question of Being[13], we must look for the right entity that can be interrogated about the question of Being – the entity which is familiar to Being. Heidegger identifies this kind of entity as Dasein,[14] which refers to human being. He states, “The being whose analysis our task is, is always we ourselves. The Being of this being is always mine.”[15] It is therefore human being or Dasein is the right entity to be interrogated. Heidegger says:

Thus to work out the question of being means to make a being– one who questions– transparent in its being. Asking question, as a mode of being of a being, is itself essentially determined by what is asked about in it – being. This being which we ourselves in each case are and which includes inquiry among the possibilities of its being we formulate terminologically as Da-sein. The explicit and lucid formulation of the question of the meaning of being requires a prior suitable explication of a being (Da-sein) with regard to its being.[16]

The selection above says, for Heidegger, Dasein is the right entity to be interrogated in dealing the issue of Being. It is because if we interrogate the entity of ourselves, which is familiar with Being, we may be able to formulate the question about the meaning of being in a more adequate way. Michael Inwood puts the term Dasein in a way to refer to both human being and to the being that humans have. The verb dasein means ‘to exist’ or ‘to be there, to be here’. The noun Dasein is used by some philosophers like Kant to signify the existence of any entity, but for Heidegger the term Dasein restricts to human beings.[17] Heidegger emphasizes that we are the kind of entities that already have this minute understanding regarding the meaning of Being. Hence, Heidegger focuses his study now on how to know or understand Da-sein,[18] which is a more available kind of being that we can know. These are the ideas about the retrieval of the question of being that serves as the way for Martin Heidegger in introducing the notion of Dasein.

[1] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. by Joan Stambaugh, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1996), 49.

[2]“Martin Heidegger”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed August 25, 2016, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heidegger/#Car.

[3] “Martin Heidegger,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed August 25, 2016, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heidegger/#Car.

[4] Martin Heidegger, What is Philosophy? trans. William Kluback and Jean T. Wilde, (USA: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1958), 55.

[5] Martin Heidegger, What is Philosophy? trans. William Kluback and Jean T. Wilde, (USA: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1958), 55.

[6] Martin Heidegger, What is Philosophy? trans. William Kluback and Jean T. Wilde, (USA: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1958), 55.

[7] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, 1.

[8] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, 2.

[9] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, 3.

[10] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, 3.

[11] Richard Polt, Heidegger: An Introduction, (Ithaca, NY: Corell University Press, 1999), 28.

[12] Patricia Altenbernd Johnson, On Heidegger, 13.

[13] The Being with a capital B refers to the meaning of being or the Beingness of the being, while the being with a small b refers to the structure of the being or the entity of the being itself.

[14] The term Dasein remains untranslated in most of Heidegger’s works. “Dasein denotes that being for whom Being itself is at issue, for whom being is the question.” (Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. by Gregory fried and Richard Polt, London: Yale University Press, 2000, xi).

[15]Heidegger, Being and Time, 39.

.

[16] Heidegger, Being and Time, 6.

[17] Michael Inwood, Heidegger, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997),15-18. In addition, it is noteworthy to consider the reasons why Heidegger introduces the term ‘Dasein’ instead of human beings. First, in lieu with the term human beings which is applied to Dasein in German usage, Heidegger prefers to use Dasein to give distinction and appropriation in his investigation which is ontology. Second, in order to avoid prejudices and misleading concepts that come along the term ‘human being’ such as ‘subjectivity’, ‘coconsciousness’, ‘soul’ and the like. Lastly, in order to devoid misleading implication. Stephen Mulhall, Heidegger and Being and Time, (New York: Routledge, 1996), 14.

[18] It can be observed that “sometimes, but not always, Heidegger hyphenates the word ‘Da-sein’, to stress the sense of ‘being (t)here’.” See, Michael Inwood, Heidegger,(New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 18.