Uncovering the Original Perennial Tradition

Introduction

The search for the origin of all religion is rather self-explanatory in its reasoning; such a discovery would have innumerable consequences for every culture on Earth. Naturally, it’s a search that’s been undertaken for hundreds of years, but only in the most recent century and a half has it really risen in popularity. The search typically leads to one of two conclusions; that religion developed multiple times independently, or that all modern religions can be traced back to a prehistoric original religion. The latter school of thought steers its proponents toward adopting the perennial philosophy. This is of the school of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, William James, and Aldous Huxley (though only Huxley described himself as such), and at its most basic, it states that every religion around today has some grain of truth in it, for they all stem from some distant but discernible divine truth. Unfortunately, but also unsurprisingly, the totality of this truth is lost. Huxley himself ascribes it only a few basic characteristics in his essay Vedanta and the West:

“That there is a Godhead or Ground, which is the unmanifested principle of all manifestation.

That the Ground is transcendent and immanent.

That it is possible for human beings to love, know and, from virtually, to become actually identified with the Ground.

That to achieve this unitive knowledge, to realize this supreme identity, is the final end and purpose of human existence.

That there is a Law or Dharma, which must be obeyed, a Tao or Way, which must be followed, if men are to achieve their final end.

That the more there is of self, the less there is of the Godhead; and that the Tao is therefore a way of humility and love, the Dharma a living Law of mortification and self-transcending awareness.”

Clearly, this is but a barebones explanation. While Huxley’s vagueness is certainly understandable, it’s of little help to those who seek a more thorough answer, for it leads many different people to declare many different names for this original perennial tradition; names like shamanism, animism, hylozoism, panpsychism, pantheism, ancestor worship, and animal cults are often thrown around and interchanged with little understanding of their actual meanings. What do these and other terms all boil down to, then? How did these different strands of thought interact and intermingle in the primordial world? And, perhaps most importantly, can we in the modern day paint an accurate picture of this original perennial tradition?

Modern Misconceptions

People tend to believe two grossly misleading things about the original perennial tradition; that it was significantly simpler than the religions of today, and that we can understand it by looking at modern indigenous religions. The former is where one-word descriptions of primordial belief systems come into play. We must understand that anatomically modern humans have been around for a solid 200,000 years, and that the Agricultural Revolution only happened 12,000 years ago. Every single (formal) religion, along with all of their complexities, developed since then. Having had 188,000(ish) years to develop before this, there’s no reason aboriginal religions would’ve been simplistic things.

Despite this, many people – even many academics of decades past – have imagined indigenous religions as overly simplistic because of how rich and complicated modern religions seem to be in comparison to them. This sort of worldview ignores a very simple fact about indigenous religions; most of their traditions were purposefully destroyed. Oral traditions in the New World, Oceania, Africa, Asia, and even Europe have been ruined by disease, genocide, and the banning of indigenous traditions and languages. Religious texts have been routinely burned by all kinds of cultures throughout history. Forced conversions and other such suppressions suffered under imperialist powers have left many modern indigenous populations without much knowledge left about their ancestral practices. Their belief systems, where they’ve survived at all, have survived in only fragments, and these fragments bear the scars of hundreds of years under the yoke of opposing belief systems. Indigenous religions, and, by extension, the original perennial tradition, were never inherently simpler than more modern religions; they’ve just been whittled down to their bare essentials. Thus, we should take care not to oversimplify our forefathers’ beliefs.

Shamanism & Its Offshoots

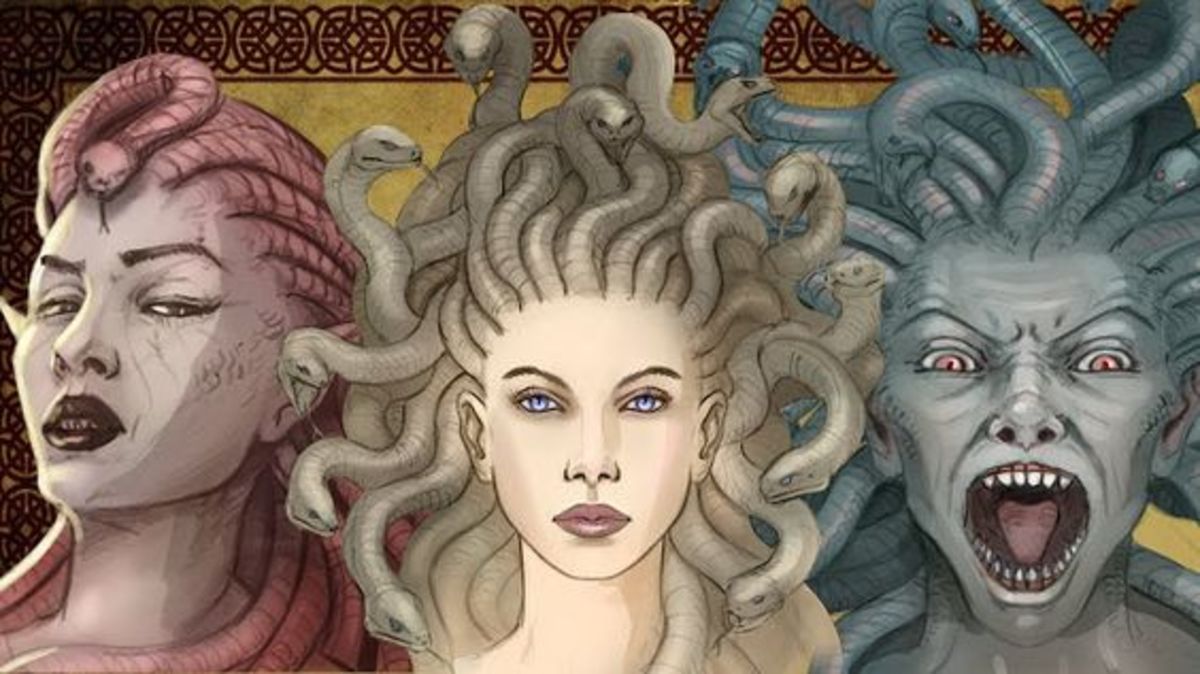

With that out of the way, we can get to dissecting some of the most commonly used terms in reference to the original perennial tradition. Shamanism and animism are perhaps the two most often brought up, both appearing innumerable times in discussions of indigenous religions. Now, in the modern day, “shamanism” is a word which often sees its definition battled over. Most succinctly, though, we can describe it as a series of practices designed to induce altered states of consciousness. Typically, this gives rise to the role of the shaman, who is designated to either enter altered states themselves or guide others to entering them. In the shamanic worldview, the aim of the altered state is to enter into a very real spirit or dream world, in which the shaman can interact with spirits and attain knowledge that can then improve the lives of those in the waking world. This practice makes lots of intuitive sense as an origin of religion. The logic lines up perfectly; early humans accidentally entering altered states would assign them great significance, and they’d thus seek to repeat these experiences in an organized manner. Hence, a shamanic tradition would begin to bloom – a process that could potentially happen innumerable times across cultures – and this would form the universal basis of all religion.

This even explains the phenomena of animal cults and ancestor worship. Particular animals were often seen by shamanic societies as being possessed by particular spirits – perhaps an outgrowth of a wish to emulate the strengths of these animals – and the shaman would thus try to associate themselves with the animal in order to channel the animal’s spirit. This is why we often see shamans adorning themselves with the horns, skins, teeth, feathers, or other parts of particular animals. It’s not hard to see how this could’ve evolved into a cult around one animal whose qualities were held above the rest. A somewhat similar process led to the worship of the ancestors. Veneration and remembrance of the ancestors were already widespread amongst ancient cultures; the old Norse poem Hávamál states as much when it declares that “cattle die, kinsmen die, and you too shall also die. But I know one thing that never dies, and that is the glory of the great dead.” A veneration for a particular ancestor, their qualities, or their deeds, could’ve very well evolved into worship. It’s also possible that direct contact could’ve led to worship; some modern Amazonian shamans claim to be able to communicate with the dead via the ayahuasca brew, which could also very well lead to worship. That will have to be a story for another day, though. Having gone over all of that, we can comfortably claim to understand the basics of shamanism.

Animism & Its Offshoots

The second term that people popularly use to describe primordial religion is “animism”, and here, we find precisely why it’s so troublesome to try to use one word to sum up something so vast. Animism isn’t just another word for shamanism, but it isn’t incompatible, either. Animism can be best described as the worldview which arises from a shamanic practice, or perhaps, the worldview upon which a shamanic practice is built, for animism is the belief that all things are imbued with a spirit. This can come in a variety of forms, as it’s most often used as a blanket term to highlight the similarities between a plethora of different indigenous traditions. Most commonly, however, it means that all natural phenomena have a spirit that either physically inhabits them, or, acting from some non-physical place, compels them to act the way they do. Thus, in animism, the Abrahamic and rationalist ideas of mankind’s consciousness being a unique thing in the world are completely absent. Animals, plants, landscapes, waters, and the weather all have spirits imbued in them, and these infinite spirits all combine to form a highly interconnected web of being. Thus, the “good life”, in an animistic worldview, doesn’t stem from one dominating their neighbors and conquering the web of being. Instead, the good life stems from playing one’s part. Man, in animism, is not meant to be the conqueror of the world, driven by lust and wanton ambition. He is meant to be a caretaker, overlooking the web of being and ensuring its continued thriving, driven only by love for the world and his place within it.

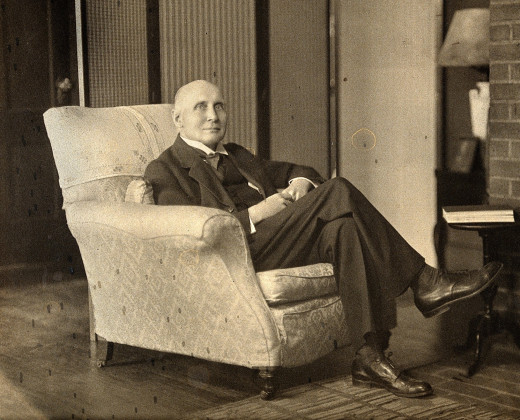

Such a worldview, to Western ears, may sound like something reserved for isolated tribes or pre-agricultural nomads, but in fact, it’s a staple of even our own tradition. The animism of the West just likes to mask itself under other names. Hylozoism, or the belief that all things are alive (just not necessarily conscious), is clearly very close to the doctrine that all things have spirit, and this belief was common among some of the most famous Greek philosophers, such as Thales of Miletus and Heraclitus of Ephesus. Panpsychism, or the belief that all things are imbued with some degree of consciousness, emerged from the earlier hylozoist schools, and has since been embraced by modern thinkers like Alfred North Whitehead and Giulio Tononi. And it doesn’t even end there. Those who entertain panpsychism can quickly discover pantheism, or the belief that the summation of nature is a conscious cosmic entity that can be identified with God. Less commonly, panpsychism blooms into panentheism, or the belief that God is not only the summation of nature, but is, in fact, both eminent in and outside of nature. Lastly, in Western schools that don’t explicitly call themselves hylozoist, panpsychist, pantheist, or panentheist, ideas of the Logos or the World Soul are everywhere, which share obvious relations to animism and its offshoots. Thus, we can see that animism is imbedded in both distant lands and our own backyards.

The Primordial Belief System

Now, above all of the lesser differences between the two strains of thought explored above, one difference reigns supreme. Simply put, shamanism is a practice, and animism is a worldview. This, of course, begs the chicken-or-egg question of which one preceded the other, but since the history of religion stretches back many tens of thousands of mysterious years, that may be a question that’ll never get an answer. Meanwhile, one question that we can answer is that of how a shamanic practice and an animistic worldview intermingled to form the original perennial tradition. There’s no dramatic buildup to be had here. The answer is as simple as can be; the spirit world of animism is the one that the shaman of shamanism taps into. Thus, one cannot really exist without the aid of the other. Now, their intertwined relationship isn’t really a precisely defined thing, but that hasn't stopped historians from theorizing about it en masse.

Most historians, from the famous (and infamous) Mircea Eliade to the many men and women in the field today, have seen the shaman as the link between the human community and the wider world of supernatural spirits. The animistic worldview is one of plants, animals, natural features, and weather patterns having specific spirits attached to them. In such a worldview, every one of these spirits is in harmony with all the others, creating a great web of being that extends throughout the natural world. It is the job of the shaman, then, to keep their own spirit (and, as the spiritual leader of their community, their spirit is essentially a representative of the community) in accordance with this wider web of being. The shaman enters into the spirit world to receive what information they needed to restore harmony, typically in a medicinal or social sense. Of course, harmonious human community would promote harmony in the rest of nature, as well, as the animistic worldview stresses the interconnectedness of all things. Thus, the original perennial traditional is most simply summed up as a tradition of shamans acting as intermediaries between the human and spirit world in pursuit of a harmonious existence.

A Modern Syncretism

Up to this point, we’ve been discussing ideas that’ve been around for thousands of years. Now, it’s crucial we bring things back around to today. In recent decades, we’ve seen the rise of two main schools of thought descending from ancient ideas of shamanism and animism; that of the neo-shamanic New Age, and that of the scientific panpsychists. Firstly, it should be noted that this obviously excludes modern practitioners of indigenous traditions, as those aren’t exactly the same thing. Such practitioners make no attempts at progressing their traditions to keep up with modernity; their focus is on preserving their traditions, rather than adapting them. Neo-shamanism and scientific panpsychism, meanwhile, make every effort possible at progressing and converting. The New Age movement has drawn the ire of experts from just about every field (largely because New Agers can’t resist throwing their theories into every field like some kind of intellectual Molotov cocktail), and their neo-shamanism is no exception. Basically, it’s an appropriation of old shamanic practices refitted for modernity, but with twice the altered states and none of the ritual, background knowledge, or community aid. This has been rightfully lambasted as a bastardization of actual shamanic practices, as it ignores crucial elements of indigenous practices in favor of a watering down that can fit into the movement’s million other metaphysical ideas.

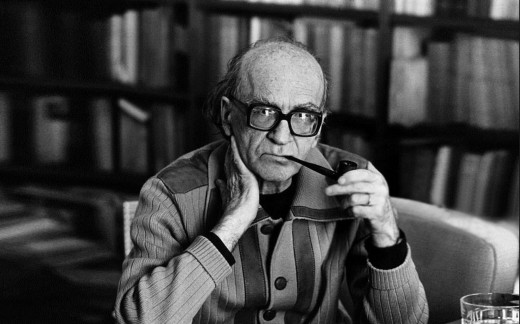

Hope for a future renewal of the original perennial tradition must rest with what’s here termed the scientific panpsychists, then. It is, fortunately, a school in good company – pioneered by people like Alfred North Whitehead, David Chalmers, and Giulio Tononi, and elaborated on in offshoot schools of thought like panexperientialism and cosmopsychism. In this tradition, old ideas of animism are rebirthed in their panpsychist varieties, but this time, it’s with the sharp eye of analytic philosophy and scientific scrutiny to back it up. The hard problem of consciousness, or the mind-body problem, which arises from the impossibility of reconciling science with the view of matter and consciousness as existing separately, has brought about a crisis in scientific circles. Our old models of consciousness simply don’t work in light of recent discoveries in neuroscience and quantum mechanics. Scientific panpsychism gets around this issue by positing the existence of a baseline level of consciousness imbued in even the simplest of matter. This doesn’t, mind you, imply intelligence in all matter. Instead, it states that the building blocks of intelligence are ever-present in matter as a fundamental element of it. When competing theories declare consciousness to exist entirely separately from matter (dualism), or not exist at all as anything more than a neural trick (physicalism), it’s a convincing argument.

Thus, the original perennial tradition – a tradition built upon the practice of shamanism and the worldview of animism – may not, after all, just be an irrelevant and long-dead belief system. It may, in fact, be able to form the basis of a new understanding of both the nature of reality and our attitudes about it. Science might just be taking its time to tell us what our ancestors intuitively knew many millennia ago.

Sources & Further Reading

https://aeon.co/essays/why-did-shamanism-evolve-in-societies-all-around-the-globe

https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/ethnobotany/Mind_and_Spirit/shamans.shtml

http://geocities.ws/john_russey/philosophy/Panpsychism_in_the_West_Skrbina.html

https://hraf.yale.edu/cross-culturally-exploring-the-concept-of-shamanism/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1460759?seq=1

https://kahpi.net/ayahuasca-ancestors-grief-death/

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/topics/reference/neolithic-agricultural-revolution/

http://www.nyu.edu/classes/keefer/nature/harkins.htm

http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/animalcults.htm

https://www.yourgenome.org/stories/evolution-of-modern-humans