Unusual Atheist Objections to Religion

Unrecognized but Common: Every-Day Atheist Arguments and Complaints You Didn’t Know

Everyone is more or less prepared for what they expect to hear from an Internet Infidel (which, let’s face it, are the same things you’d hear if the person wasn’t online). These include such tropes as “if God is real, why is there so much suffering?”, “Don’t bring your religion into politics!” and “Religion is holding society (especially science) back!”

However, there are some very common arguments and objections that people aren’t as aware of. In fact, these objections are so fundamental to most Atheist’s perception of Christianity, that being aware of them makes for a very informative window into the belief structure that drives modern atheism. Let’s examine a few of these.

Religious indoctrination of children

This particular complaint is probably not terribly surprising. One assumes that atheists believe that religion indoctrinates all of its followers. What makes the objection toward children unique?

Yet this is a complaint one is likely to find on the lips of practically every atheist. In its most aggressive form, one is likely to hear that Christians shouldn’t even be allowed to raise children. That Christianity is tantamount to child abuse, and similarly alarmist statements.

What drives this vitriolic objection?

It possibly originates with the battle cry of celebrity atheist Richard Dawkins who, at the Chipping Norton Literary Festival in 2013, gave a speech in which he stated:

“'What a child should be taught is that religion exists; that some people believe this and some people believe that.

'What a child should never be taught is that you are a Catholic or Muslim child, therefore that is what you believe. That's child abuse.”

This cry was taken up thereafter by people like novelist Zoltan Istvan who, in his 2014 Huffington Post article titled “Some Atheists and Transhumanists are Asking: Should it be Illegal to Indoctrinate Kids With Religion?” says,

“Like some other atheists and transhumanists, I join in calling for regulation that restricts religious indoctrination of children until they reach, let’s say, 16 years of age. Once a kid hits their mid-teens, let them have at it—if religion is something that interests them.”

Istvan’s argument is that:

-

Human beings are limited enough such that it is foolish to make claims to grand spiritual knowledge in the way that religions do

-

A child’s mind is terribly susceptible

-

Ideas a child absorbs when they are at the most susceptible phase of life are difficult to shake in adulthood, such that their religious indoctrination will likely stifle their development for life.

Istvan resolves his article by stating that, while he is not calling for religion to be made illegal, he is calling for people to only be exposed to it when they are adults and capable of making up their own minds. Says Istvan:

“An appropriate analogy of religion is that it’s kind of like porn—which means it’s not something one would expose a child to.”

This is possibly an irresolvable dilemma between Christians and atheists. All people have preconceptions, beliefs and attitudes which – regardless of how they are raised – they cannot help but to absorb from their parents.

Take, for instance, atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell who, at his Beacon Hill educational center, attempted to raise his daughter in such a way as to give her all possible explanations for a subject and then compelling her to make up her own mind. In her book My Father Bertrand Russell, Katherine Tait describes the process:

“‘making up our own minds’ usually meant agreeing with my father, because he knew so much more and could argue so much better; also because we heard ‘the other side’ only from people who disagreed with it. There was never a cogent presentation of the Christian faith, for instance, from someone who really believed in it.”

Unsurprisingly, Tait grew up to be an atheist, like her father.

Tellingly, once she actually investigated Christianity on her own, she eventually became a Christian. But not before she totally absorbed the atheism of her father.

Children, however, will echo the nature, beliefs and characteristics of their parents, no matter how the parents would wish they didn't. So in practice, this kind of legislation would be fairly ineffective except, alarmingly, to give the government permission to closely monitor and potentially remove children from Christian households.

But if a child adopts a belief from his or her parents which is not a true belief, what is the problem? Hasn't this kind of thing been going on since children and parents began to exist?

Istvan explains the problem he sees:

"Religious child soldiers carrying AK-47s. Bullying, anti-gay Jesus kids. Infant genital mutilation. Teenage suicide bombers. Child Hindu brides. No matter where you look, if adults are participating in dogmatic religions, then they are also pushing those same ideologies onto their kids."

The upshot of this objection is that religion is dangerous and harmful, therefore children should be kept from participating. If one accepts the first premise, then one must accept the second.

However, Christianity has been and remains a strong influence on Western society and has been, for the most part, either completely constructive or at least relatively tame. It is only in recent years when political ideology has progressed in such a way as to chafe against the most fundamental of Judeo-Christian values that this has become a concern.

Much like Istvan's call for "regulations that restricts religious indoctrination of children until they reach 16 years of age," this universal imposition on the prerogatives of parents lies more in the realm of politics than it does religion. Christians aren't encouraging their children to riot, kill, steal or rape; but they might teach their children to value the traditional family unit, which runs increasingly counter to the cultural zeitgeist.

Regardless, childhood development inevitably leads to a stage in adolescence when children naturally investigate the values they have been taught, and test the boundaries of their parent's authority and knowledge. They will tend to absorb their adult values from their environment more than from their background. Psychologist Luke Gailen, for instance, notes that:

“While intelligence can be reliably measured at an early age, religiosity cannot. If you take a measure of a person’s religiosity early on, it doesn’t prove at all if they are going to be religious as an adult.”

So ultimately, upbringing has less control over a child's adult values than conventional atheist wisdom might indicate.

Worship

A surprisingly common idea among atheists is that the God of the Bible demands worship or condemns the person who fails to worship. This, they seem to suppose, is the cardinal sin: failing to worship.

This is, perhaps summed up best by a question a skeptic once asked Christian Apologist J. Warner Wallace:

“So, whilst you state that god doesn’t demand worship, he DOES threaten dire punishments to those who don’t worship him!

‘You don’t have to worship me, and I’d never ask such a thing of you, but if you don’t I’ll crush you, and your kids, and THEIR kids, just to make sure my message is clear’ seems to be the way god is saying things are.

So, here we have a supposed perfect being, in a supposed revelation in his supposed holy book, saying that he’ll be angry if he isn’t worshipped!

We come back to the question – why would a perfect demand worship?”

This is the demand as it is often portrayed: Worship or Hell.

This particular objection may seem confusing at first flush. Why should it be so objectionable that, of all the things God might demand, Worship should be among the worst. Keeping in mind that the atheist posing the objection doesn't believe in God, based on the objection, one supposes that even if they did believe in God, they would bulk at the idea of worshiping him.

At the end of the day, God might lay down a number of rules in scripture, but none of them demand worship. If anything, worship is assumed. Much like it is natural to assume that a spouse might show affection, a friend might show loyalty and an employee might show dedication; so it is supposed that a believer will show worship.

In fact, when one considers the joyful and dedicated nature of worship, to suppose that people are doing it out of fear or obligation is akin to the old joke, "The beatings will continue until morale improves," or forcing an employee to smile at customers. Unless the worship is felt it is not worship at all.

Simply put, worship is a byproduct of having a relationship with God. The natural response to recognizing things about God and his nature is to worship. This may be clearly seen in the Psalms – the most worshipful segment of the Bible – where the Psalmist says things like, "For you, O Lord, have made me glad by your work; at the works of your hands I sing for joy." Similarly, in the Gospels, when Jesus performed a feat of healing, exorcism or similar miraculous work, the frequent response of the people was to "give praise to God."

When worship is given in the Bible, it almost always a reaction to either the work of God, or a realization about him; not a forced procedure.

That this particular idea – worship – should be so objectionable may be very instructive about the person raising the objection in the first place.

Political Law and Moral Authority

The first section of this article discussed the idea that, according to Zoltan Istvan, instructing a young child in one's religious convictions should be legally forbidden such that the government would retain the right to remove the child from the care of religious parents.

If one pays attention, this kind of rhetoric – that things an atheist doesn't like should be made illegal – is almost universal. This can be seen in the increasingly common actions atheist organizations such as Freedom From Religion take, using the legal process to remove religious icons from the public sector.

This writer once even heard an atheist propose that "deathbed conversions should be made illegal." The question of how, exactly, such a law might be enforced makes the mind boggle.

This kind of thought process: that the government is the end-all and be-all of moral authority, is nothing if not predictable from an atheist perspective. Once one removes any abstract or transcendent basis for Moral Law, then it must lie in some physical institution. That political law is entirely arbitrary doesn't seem to be much of a problem.

If one argues, as Istvan does, that children ought to be removed from religious parent's home, one is appealing to some kind of principle that lies outside of current law. One is appealing to a moral standard that transcends government in order to suggest what laws government ought to make.

The person that holds that the government is the determiner of moral law is often inconsistent with their own viewpoint.

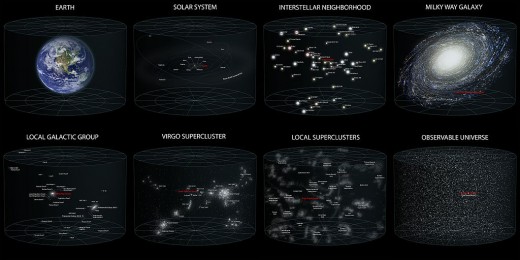

Size of the Universe

This is a fairly common objection: that humans can't be special in the way that Christians seem to believe because the universe is a big place in comparison to human beings.

This objection seems to operate from the premise that size is the determiner of value. The bigger the thing, the more valuable it must be, such that, say, a proton must be worthless in a universe so large. Although one might expect the counterargument to that is that there is such an abundance of protons in the universe that they become significant by sheer numbers.

However, when one considers the way in which humans – the only conscious and intelligent beings with which we have direct reference – value things, it quickly becomes clear that size is not much of a determiner of value. If anything, scarcity determines value. If diamonds were piled along the coastline like sand, they would suddenly be worthless. The first issue of the Superman comic is worth a small fortune because there are practically none left, whereas the most recent issue of Superman which has just shipped by the truck-load around the world, is barely worth the cost of the paper on which it is printed.

There are more stars in the universe than there are people who have ever lived, and people contain the quality of self-awareness and the abilities of comprehension and meta-cognition. Despite their small size, their uniqueness and scarcity speaks for itself.

Aliens

This is not the sort of objection which Christians often consider, but the potential existence of alien life is brought to bare more frequently than one might imagine as a defeater for, of all things, the existence of God.

Why? Several reasons. If life were to be discovered outside of planet earth, it might indicate that the process of abiogenisis – that is, the development of life from lifeless matter – is not exclusive to earth, and therefore can be explained without divine intervention.

Perhaps more defeating is the idea that – if it were found that there were self-aware, conscious beings capable of making moral judgements – then the entire idea of God judging people and sending them to heaven and hell, and even sending his Son in human form to die on the cross and so forth – becomes a human-centric story that does not fit the larger paradigm of intelligent beings across the universe.

Indeed, the idea that Christ will, for eternity, sit at his Father's right hand in a glorified human body entirely excludes alien races.

This is not, however, as problematic as one might suppose. Firstly, the idea that God could not, or would not create or allow life to spring up elsewhere in the universe is not necessarily contradicted either by doctrine or scripture. There is, if anything, a superfluous amount of life on earth. How is finding a new kind of bacteria or fish in a volcanic vent in the ocean any different than finding the same thing on another planet?

Concerning abiogenesis: regardless of how God chose to bring about the existence of living things on earth, doing so on another planet seems to challenge nothing about God's power, nature, design, etc.

The second challenge: the story of human redemption (vs. Alien redemption), may seem a bit more challenging until one considers that Christianity already allows for non-terrestrial, conscious moral agents. They are called "angels." In fact, the Bible describes a variety of celestial beings which interact in some way with God, and do so volitionally and intelligently.

Do these beings have the same redemptive relationship with God as do humans? Almost certainly not. But the fact that their relationship with God differs from that of humans, in no way challenges Christian doctrine.

If it were discovered that aliens exist, there is no need to compare their relationship with God to that of humans. This simply is a non-issue and not doctrinally threatening.

Conclusion

Atheists are ever-imaginative in the ways they choose to challenge religion. Some of these ways are peculiar to their own philosophies and proclivities, and some are simply the product of imagination. But it is the former which drives most of these objections, and the objections themselves are a window into the concepts which drive the atheist worldview.

It never hurts to open friendly dialogues on these questions, but they are worth preparing for.