William Wilberforce's Appeal to Great Britain to end Atlantic Slave Trade & Slavery

Young William

From Gradual to Immediate Emancipation

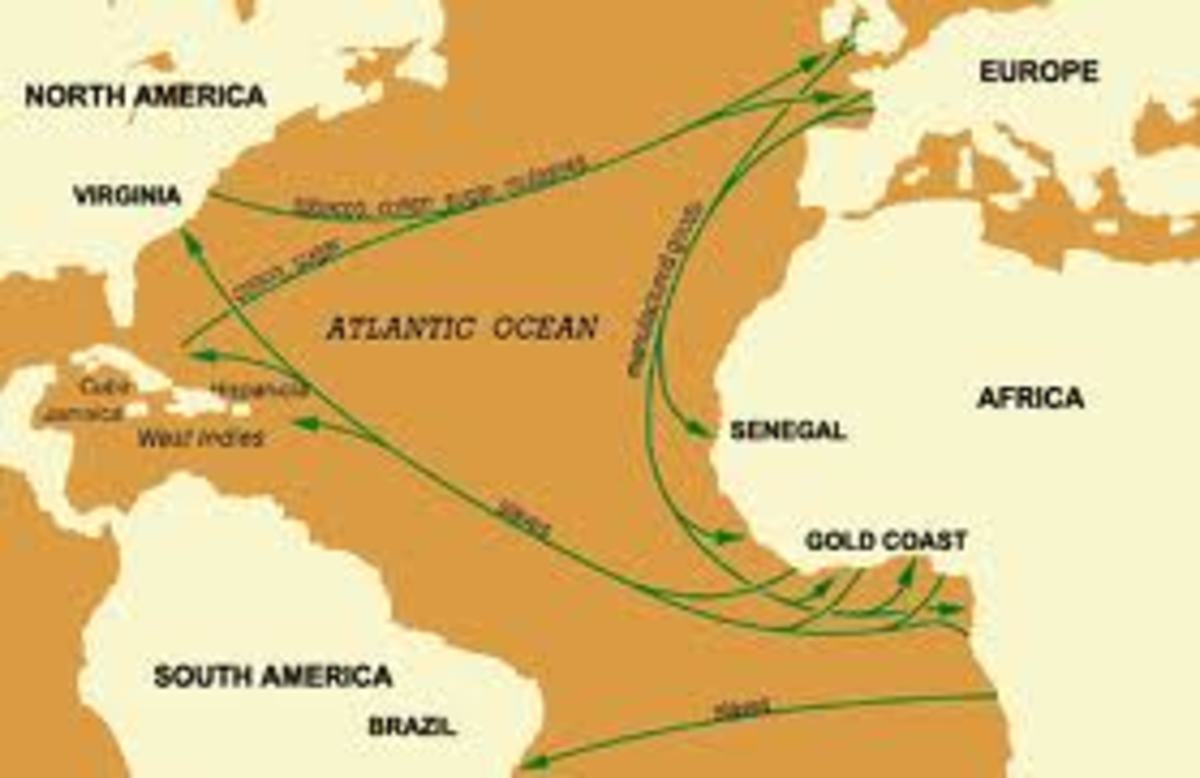

When William Wilberforce wrote An Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire, in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies , in 1823, he was sixty-four years old. He was a man of great humanitarian accomplishment, having initiated and participated in many social reforms, including Great Britain’s abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1807.[1] Though Wilberforce was still a member of the Parliament in the House of Commons, An Appeal was addressed to “all inhabitants of the British Empire who value the favour of God or are alive to the interests or honour of their country – to all who have any respect for justice, or any feelings of humanity”.[2]An Appeal was written for the purpose of changing the hearts and minds of its audience, a new generation as well as the old, in order to effectively terminate Negro slavery in the British Colonies.

Taking a firm stand at odds with many of his fellow abolitionists, Wilberforce was originally in favor of the gradual emancipation of slaves because of the economic implications to Great Britain, especially the loss of the slave labor and the creation of a class of citizens unable to succeed in a free society. But by the time An Appeal was written, he was an adamant supporter of immediate emancipation. In examining An Appeal, it is apparent that this transformation in Wilberforce’s thinking was due to three main reasons. First, over the span of his life, Wilberforce had a growing Christian conviction that slavery was Biblically wrong; therefore, he came to believe abolishing it was key to the salvation of Great Britain. Second, Wilberforce realized it was no longer economically feasible for Great Britain to continue slavery. Third, Wilberforce acknowledged that his plan for ending the Atlantic Slave Trade in order to eventually end slavery had failed, mainly because of Parliament’s deliberate lack of action to enforce the plan of gradual emancipation.

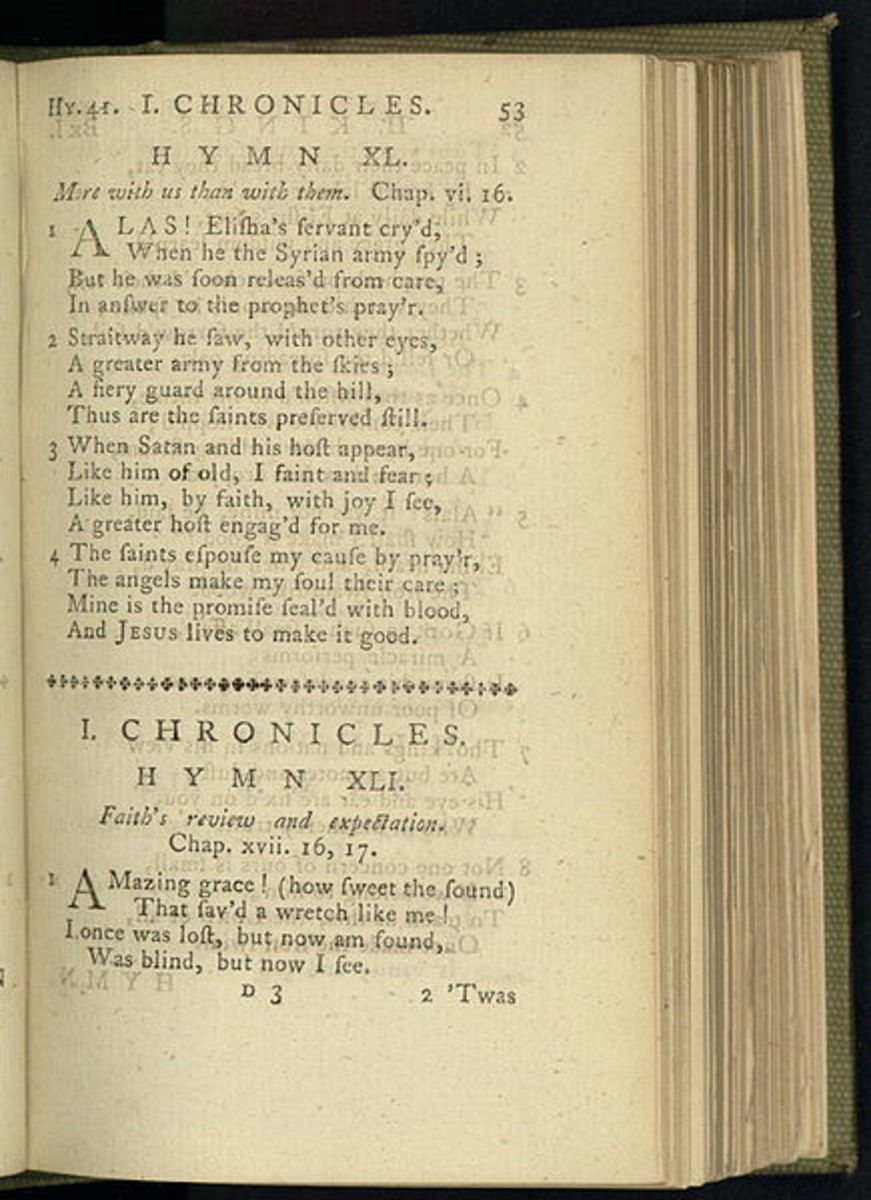

Wilberforce was brought up in the traditional Church of England by his mother and grandfather. However, through his aunt and uncle, great supporters of George Whitefield, Methodist preacher and Europe’s Great Awakening leader, he was heavily influenced by and interested in evangelical Christianity. But it was only after a tour of Europe in October of 1784 that Wilberforce had a conversion experience and became an evangelical Christian. After reading The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul, by Philip Doddridge, an early 18th Century English nonconformist and hymn writer, and considerable prayer, Wilberforce committed himself to working in the service of God. However, he struggled with himself continually, being self-critical, judging his spirituality, which affected his relationships with others. Wilberforce’s later speeches and writings reflect the reluctantly acquired wisdom that comes with experience in dealing with an issue such as the Slave Trade. In his writing, A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in This Country, Contrasted With Real Christianity, it is clear that Wilberforce had finally come to the realization that his loyalties were divided. [3] He felt responsible to the Parliament and Great Britain’s people, but also for those in bondage. He was at the point in his life where he had to make a decision about his priorities, and he chose the lives of those in bondage.

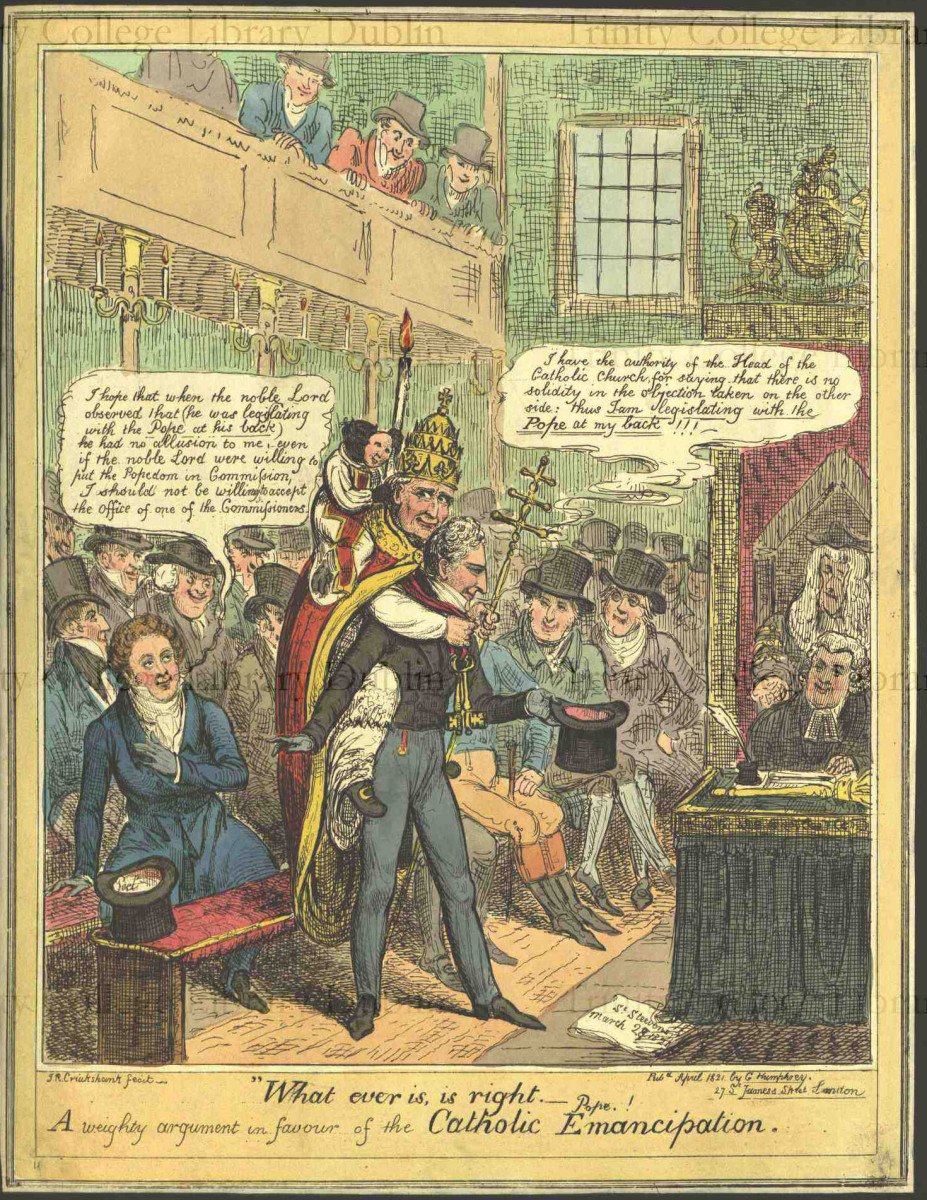

As a Christian, Wilberforce stated in An Appeal that he considered Great Britain to be a Christian country. [4] While Christianity and its tenets were paramount to Wilberforce, he required the reader to go beyond the nominal Christianity to which the reader was accustomed, calling his fellow countrymen and Christian brothers into action, both individually and collectively. Using critical analysis of the Bible to obtain a list of natural rights for human beings, Wilberforce did not come against the church as an institution. In fact, he was a great supporter and member of the Evangelical Branch of the Anglican Church, and later belonged to the Clapham Sect, which stressed practical Christianity. Wilberforce did, however, come against the church-goer as a nominal Christian. He wanted to end the complacency of nominal Christianity. Wilberforce was not basing his Christian principles strictly on the authority of the church or on its dogma but on what he considered to be reasonable conclusions gathered by studying the Bible. In this respect, Wilberforce went beyond the social norms, through grassroots movement and arguing in the governmental system for abolition of the Slave Trade. Then through An Appeal, he addressed and challenged the people of Great Britain, the majority of whom claimed Christianity as their religion. Wilberforce wrote that there was a higher authority to which his reader will eventually answer “in the great day of account, for the use they shall have made of any power or influence with which Providence many have entrusted them, to employ their best endeavours.” This was neither a call nor a warning to do what God in his high authority commanded without question. Rather, it was a statement of fact that the reader had been entrusted with the power and influence, i.e., the reason and ability, to do the best they could do for God to insure that certain basic natural rights were obtained for all humankind, including Negro slaves. Wilberforce truly believed that recognizing those rights was going to make the difference between the spiritual destruction and salvation of Great Britain.

Wilberforce was a classical liberal. Classical liberalism can be best defined as a political belief that emphasizes freedom of the individual by limiting government power and advocating economic freedom for private property and the free market. Wilberforce was not against free market. As a matter of fact, it was of the utmost concern to him. His point in An Appeal was not that government should interfere with free market, but human beings, in this case Negro slaves, were, but should not be, a commodity of that free market system:

“In the contemplation of law they are not persons, but mere chattels; and as such are liable to be seized and sold by creditors and by executors, in payment of their owner’s debts; and this separately from the estates on which they are settled. By the operation of this system, the most meritorious slave who may have accumulated a little peculium, and may be living with his family in some tolerable comfort, who by long and faithful services may have endeared himself to his proprietor or manager, - who, in short, is in circumstances that mitigate greatly the evils of his condition – is liable at once to be torn for ever [sic] from his home, his family, and his friends, and to be sent to serve a new master, perhaps in another island, for the rest of his life.”[5]

Wilberforce did, however, recognize the need for government intervention to end slavery as it had the Slave Trade. He used the government, not to impede the free market, but to ensure freedom, equality, and free market for all people living under the protection of Great Britain.

As previously noted, Wilberforce was originally in favor of the gradual emancipation of slaves because of the economic implications to Great Britain both in losing the labor and in creating a class of citizens unable to succeed in a free society. But by the time An Appeal was written, he was adamant that the time for emancipation had come.[6] Calling the Slave Trade the “parent” of slavery, he pointed out the relationship of the two; the Slave Trade had begat slavery.[7] As such, the death of the Slave Trade should have resulted in the death of slavery. To Wilberforce, the economic issues supporting the gradual emancipation of slaves no longer applied in the same way that they had in the past. Wilberforce pointed out any ideas of economic wellness resulting from the end of the Atlantic Slave Trade were only misconceptions. There had been a decrease in slaves since the end of the Slave Trade, but Wilberforce explained that decrease was because of the mismanagement and mistreatment of existing Negro slaves by those who considered them to be less than human. The slaves had been denied the very basic physical and moral care which should be afforded all humans in their natural rights. Because of the large decrease in the number of slaves, it was no longer lucrative to continue a slave system of labor. Therefore any economic argument previously given by opponents of abolition to continue slavery was obsolete. In other words, the economy was better served using hired labor.

After repeated Parliamentary blocking of the enforcement of gradual emancipation, in 1815 Wilberforce publicly declared that since Parliament did not support him, he was not bound by their stance on emancipation, and thus he began his campaign for the immediate end to slavery. Wilberforce was tired of fighting a long, ineffective battle of thirty years within Parliament, so he turned his attention to changing the hearts and minds of British citizens in an effort to end slavery once and for all.[8] In the beginning, Parliamentary change was necessary to force and enforce the end of the Slave Trade and begin a legitimate means by which to change the minds of the people Great Britain and their colonies. Wilberforce recognized, however, that the next generation would have begun to accept that since the Slave Trade was obsolete, the need for slavery was obsolete as well, as Wilberforce noted: “It’s a fact that the old prejudice that negroes are creatures of an inferior nature is no longer maintained in terms, there is yet too much reason to fear that a latent impression arising from it still continues practically to operate in the colonies, and to influence the minds of those who have government of the slaves.…”[9]

Further, Wilberforce pointed out that the evils of slavery itself, previously unreformed and unnoticed, had been confirmed during the Slave Trade debate of 1792, which, as Wilberforce reiterated, was seriously and harshly debated.[10] To Wilberforce, this serious debate only served to further affirm that the need to end slavery issue was not questionable anymore. Wilberforce conceded that perhaps slavery should have been ended in 1807 with the Slave Trade, but Wilberforce truly believed that it would have been more inhumane to the slaves to end slavery abruptly without the tools, such as education, to help the newly emancipated slaves adapt. However, this was not an excuse to continue slavery forever. The original intent of the abolitionists was not only for the end of the Slave Trade but for the emancipation of the slave at a subsequent time. Wilberforce blamed Parliament for not following through with the purpose for ending the Atlantic Slave Trade.

In spite of his previous stance of gradual emancipation, Wilberforce had always taken the position that if anyone knew the true nature of slavery, each would immediately seek to end it. Then in 1823 Wilberforce finally had come to realize that there were those who were not misled, who had the opportunity to see the horrors in “their true colours”, and who had the power to end slavery, but had allowed it to continue.[11] Wilberforce seemed to have finally recognized the full extent of the slave issues. That is, he finally acknowledged that there were those who deliberately chose not to act on the basis of their Christianity, whether nominal or not. Prior to 1807, Wilberforce had appealed to the moral character of his listener. After 1807, Wilberforce began calling for accountability and responsibility not from Christians in general, but from those people who deliberately did such horrific things. This seems to have been the breakthrough for Wilberforce, allowing him complete his fight for the freedom of slaves in the face all adversity. This breakthrough finally seemed to reconcile his internal conflicts between his faith, the economic interests of a nation and his duties in Parliament regarding the welfare of all people. One can speculate that perhaps Wilberforce’s recognition of the full extent of the slavery issues was what changed the tone of Parliament and thus gave way to the passing of the 1823 Emancipation Bill.

[1] Well-known historical facts of Wilberforce and the Abolition Movement were cited from http://www.brycchancarey.com/index.htm, and http://www.hullcc.gov.uk/museumcollections, both last visited 1/5/11. [2] Wilberforce, Wm., An Appeal to the Religion, Justice, and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire, in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies. (London, J. Hatchard & Son 1823) 1. [3] Wilberforce, Wm., A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in This Country, Contrasted With Real Christianity. (Boston, Crocker & Brewster 1829). [4] An Appeal, 32. [5] An Appeal, 18. [6] The compromise of gradual emancipation was the suggestion of Henry Dundas, Home Secretary, who amended the Abolition Bill of April 2, 1792, to be complied with by 1796. The bill passed 230 to 85. It was a delay tactic used by West Indies interest groups to continue the Slave Trade. [7] An Appeal, 2. [8] There is discrepancy in various legitimate sources on when exactly the Slave Trade was challenged and when exactly Wilberforce considered the matter resolved, and there is evidence that the Slave Trade indeed continued. [9] An Appeal, 45. [10] An Appeal, 3. [11] The Parliamentary Debates from the year 1803 to the Present Time , Published by T.C. Hansand (London 1812), Vol. II, col. 99 3-4, February 23, 1807 – Slave Trade Abolition Bill, Parliamentary Archives, http://slavetrade.parliament.uk/slavetrade/assetviews/documents/speechbywilliamwilberforceinthehouseofcommons23february1807.html last visited 1/8/11.