Zombies and Ghosts in the Bible

Ghosts and Zombies in Judeo-Christianity

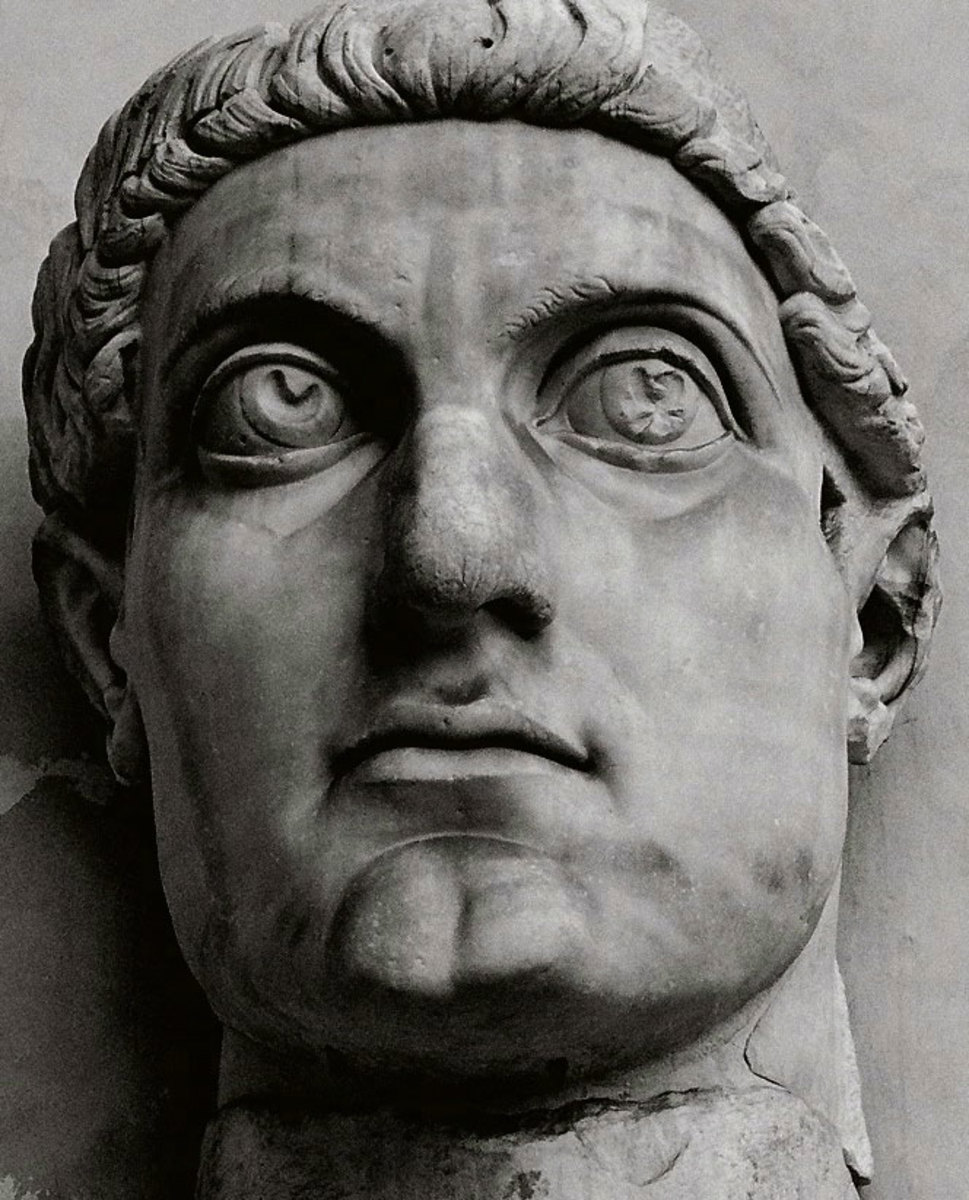

The belief in ghosts has been popular even before the first century CE when it became a principle in the development of the Christian communities and later the Christian church founded by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325 CE. This belief in supernatural beings grew along with the community of believers who followed Jesus and worked in scriptorium. The few who were literate or could make rudimentary illustrations, delighted in the depiction of "those outside of their bodies".

All those who died were subject to depiction, and after the first gospel written (John, although Mark is often given credit for this even though John is an independent account) were considered subject to tales of out-of-body beings and experiences. Even Jesus was considered a ghost (Matthew 14:25-27). Even Jesus was considered by some as a ghost after Golgotha (Luke 24:37-39).

As the cult of ghosts and zombies grew (to be later ruthlessly put down by imperial forces who were enforcing the state religion of Constantine) so too did heresies. Heresies is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as: "opinion or doctrine at variance with the orthodox or accepted doctrine, especially of a church or religious system." It was this variation of ideas that led to some of the most bloody battles for the faith, with the strong arm of the empire erasing through exile or murder those who opposed the theology current in vogue with the emperors and their retainers.

The suppression did not end heresies focusing on ghosts and zombies, but actually made them stronger. Their rise led to a variety of sects and cults. Most of these were branded as heresies and forcibly suppressed and their membership butchered.

Ghosts were far more popular in the Torah, Prophets (cf. 1 Samuel 28:7-20) and Wisdom books that make up the Old Testament. The New Testament transmogrifies "ghost" into "spirit".

The New Testament (a group of books written from the end of the first century CE through the fifth century, with nothing appearing within the first three generations after the gospels recount the death of Jesus) was initially considered more important among Greek communities, although in time it was balanced with Old Testament law and writ as demanded by the original founders of those who followed Jesus who were, like Jesus, Jews. Those who recognized the chair of James the natural brother of Jesus at Jerusalem were the most outspoken. They placed a premium on those who "were outside the body" (2 Corinthians 5:8: "away from these earthly bodies").

Many of those "outside of the body" were seen as "the living dead"--zombies (most frequently cited in Revelation 9:6 and 20:5; Isaiah 26:19-20; Ezekiel 37:3-5; Daniel 12:2; and Ecclesiastes.9:5-6). A few of those "resurrected" in their own bodies, as found in 1 Kings 17:12-24; Matthew 9:18-26; John 11:38-44; and Acts 20:9-12, found parallel recognition with the recitation of the account of the death of Jesus.

The most popular story in the bible is the resurrection of zombies who walked into Jerusalem to proclaim that Jesus was one of their own (Matthew 27:52). This became a source for the leading illustrators in presenting the Jesus story in art. Early Christian art frequently depicted zombies in bible stories on church walls until bishops began in earnest to forbid the practice, when their power of censorship was recognized by the empire and codified in the Codex Theodosius.

Since the earliest records of communities of followers of the Jesus of the gospels, known as chrestianos and christianos, began to communicate with each other, there has been a belief in ghosts. The most prevalent and mind-captivating group were known as Docetists (Dokētaí: illusionists). The Docetists practiced docetism (from the Greek δοκεῖν/δόκησις dokeĩn ("to seem") or dókēsis ("apparition", or "phantom").

Docetists believed that "Jesus" only seemed to be human. They argued that Jesus' human form was an illusion.

The Docetists had, at first, both scriptural and historical support for their belief in divine ghosts. The word Δοκηταί referred to early groups who denied Jesus' humanity. The first time that it was used occurred and is found in a letter by Bishop Serapion of Antioch (197–203).

Serapion discovered the doctrine in the Gospel of Peter, during a pastoral visit to a Christian community using it in Rhosus. As pressure mounted, Serapion later rejected it as heretical.

Docetism was unequivocally rejected at the emperor Constantine's First Council of Nicaea in 325, when Constantine created his "catholic [universal] church". Constantine's rejection of Docetism was hailed by an non-representative rump of bishops. Only a handful of bishops (overseers) present. The bishop of Rome, Pope Sylvester I (died 31 December 335), failed to appear and did not immediately ratify the Emperor's Council. Sylvester,however was represented by two legates, Vitus and Vincentius. The pope later ratified the judgment of Nicaea, but without fanfare as the Emperor was uncertain of his own interests, going between Arianism that was later called a heresy, and "orthodoxy".