Why Pews Became a Power Move in Church History (And Why They Still Matter Today)

From Stone Floors to Social Thrones

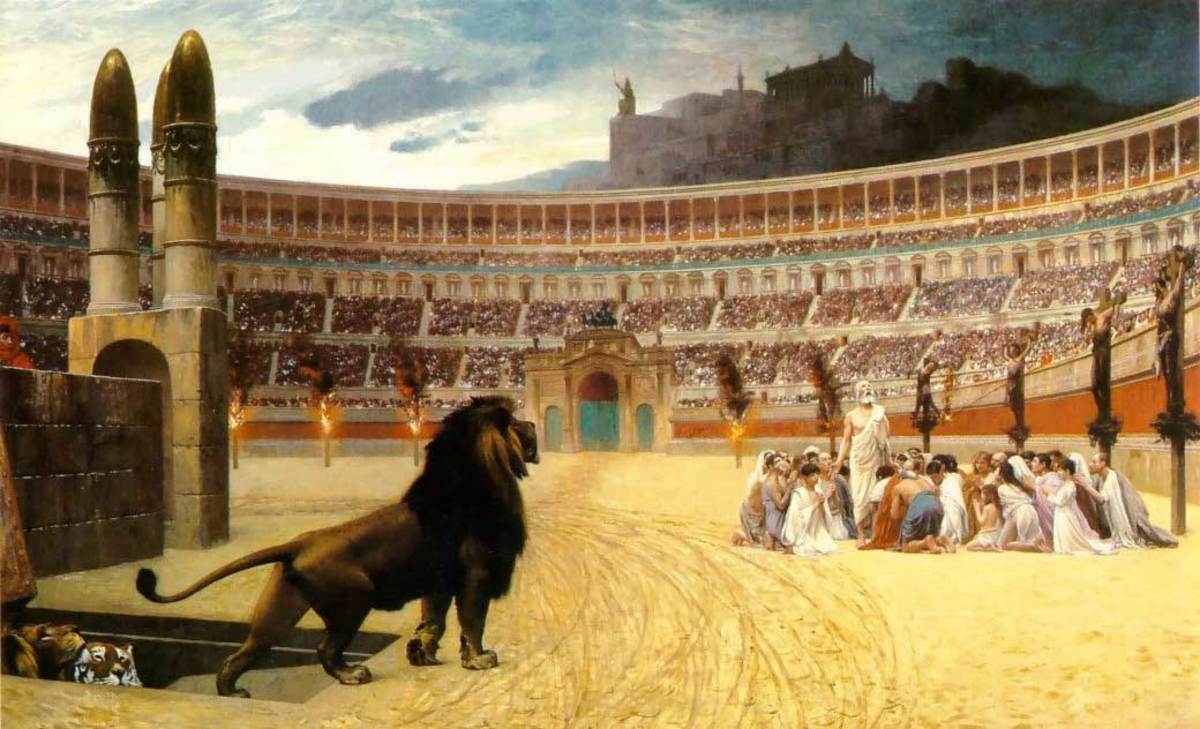

Imagine standing for hours every Sunday on a cold stone floor while the sermon drones on. That was church in the 1300s, before a piece of furniture quietly changed everything.

In the early 14th century, churches were void of seating. Worshippers stood or sat directly on the floor. Some brought along short, three-legged stools for comfort, but there were no permanent fixtures for rest. Then, somewhere around the mid-1400s, something called a “pue” began appearing in church records. Derived from the Old French pui and Latin podium, it originally referred to elevated platforms used for reading Scripture aloud. But it didn’t stop there.

Soon, fixed wooden enclosures began appearing. These “pews” provided not just comfort, but status. The more ornate the pew, the more important the occupant. Over time, seating arrangements began to mirror the social structure of the surrounding town or parish.

Before long, pews weren’t just places to sit, they were architectural expressions of class. While the altar remained the spiritual centre, the pew became the social one. The front rows weren’t open to everyone; they were occupied by those with land, title, or influence. Just as castle walls kept the elite protected, pew walls kept them prominent.

Churches were no longer just houses of worship, they were theatres of social order. And pews? They were the reserved seating.

Reserved Rights and Modern Realities

You may think no one cares where you sit, but in some churches, a few minutes late could mean you lose your place in more ways than one.

In the United States, pews evolved in a slightly different way. Most churches treat them as the property of the church corporation. They can be rented, leased, or sold to raise funds for the congregation. But whether a pew is considered real property or personal property depends on the laws of each state. Yes, there are legal precedents. Yes, people have sued over pew rights.

Modern church rules often include clauses that allow ushers to reassign pews if the rightful occupant hasn’t arrived by the start of the service. It’s like an old-school boarding pass, miss your call, and someone else takes your seat.

In many Protestant denominations, pew rentals were phased out in the 20th century, seen as incompatible with egalitarian theology. Yet some congregations still maintain reserved pews for donors or long-time members. And while newer churches might opt for chairs over pews, the psychological imprint remains.

The pew has gone from a fixed symbol of class to a relic of continuity. It still anchors families, ushers in ceremony, and holds memories, weddings, funerals, confirmations. The grain of the wood has soaked in generations of stories.

So next time you slide into a pew, remember: it’s more than just a bench. It’s a centuries-old seat of power, tradition, and quiet hierarchy. Whether you’re in the front row or tucked away in the back, you’re sitting in history.

Power in the Pews

Where you sat on Sunday didn’t just say where you stood with God, it said everything about where you stood in society.

In England’s Established Church, pews became property. Some were passed down as heirlooms, a practice known as prescriptive right. These pews stayed within families for generations, often accompanied by plaques or carvings denoting the family name. Others were at the discretion of the bishop, assigned according to rank by church wardens. Your seat was your social ID, and no one wanted to sit out of place.

Scotland took a more economic approach. Pew placement was often based on the value of rent paid by parishioners. The more you paid in rent, the closer you sat to the pulpit. Imagine seating in church based on your property tax, worship by wealth.

This wasn’t just symbolism. In both regions, pew disputes led to court cases. If someone tried to sit in your family’s designated pew, you could take legal action. Owning a pew came with rights. You could lease it, defend it, and even sell it. It became a seat with standing.

Church seating was so tightly entwined with status that even the empty pew told a story. Absence wasn’t just about skipping service, it could be seen as a public lapse in social or spiritual commitment.

The result? Church became a venue not only for prayer but also for quiet social competition. Every Sunday, congregants didn't just come to hear the word of God, they came to be seen in their rightful place.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Historia