- HubPages»

- Sports and Recreation»

- Team Sports»

- Baseball

All-Starless: Teams Undeserving of an All-Star

The Problem With Picking All-Stars

There’s an inherent problem with selecting players for the All-Star Game. For one thing, it’s supposed to be an honor for the best, yet the roster is always expanding. There’s a) the replacements due to injuries – including aches and pains that last just long enough for the break; b) more pitchers to prevent another reliever-less fiasco; c) more relievers due to the greater usage of relievers in both the regular season and the annual showcase; d) the expanding rosters to make up for the fact that there are more teams; and e) the effort to engage fans and take some of the blame off the managers by having the last guy vote-in.

Part of the challenge is that there are 15 teams in each league. A normal in-season roster would average under two players per team. When you take into account that there are several stars at the same position and other positions are weaker, that makes it more challenging.

And then there’s the fact that every team gets a representative. Now, that shouldn’t seem difficult. Pretty much every team has a real star. Maybe it’s a guy having a better season than usual, or a rising star or a big-name veteran on the way down. Right?

Actually, it’s been 40 years since every team deserved an All-Star.

Travis Wood

Using Win Shares to Rate the Best of the Worst

Bill James’ Win Shares are a great single-number ranking of a player’s contribution to his team’s victories. A season total of 30 or more Win Shares basically rates as an MVP-like season. Twenty-something Win Shares means a player put up an All-Star caliber season. A player with about 10 Win Shares over a full season contributed at a basic level of play, nothing special.

Unfortunately, except for this season, we don’t have Win Shares totals for the All-Star break. And, of course, there were no All-Star breaks before 1933. And team game totals vary, and there were a few years with two All-Star games. Plus, of course, a full season gives a better picture as to who really is a star than 80-something contests.

So, if we consider 20 Win Shares as the threshold for All-Star worthiness, which teams have fallen short? Well, there’s been a team that has not reached that standard every year since the 1974 Expos had a pair of players as the worst of the best with 20 WS.

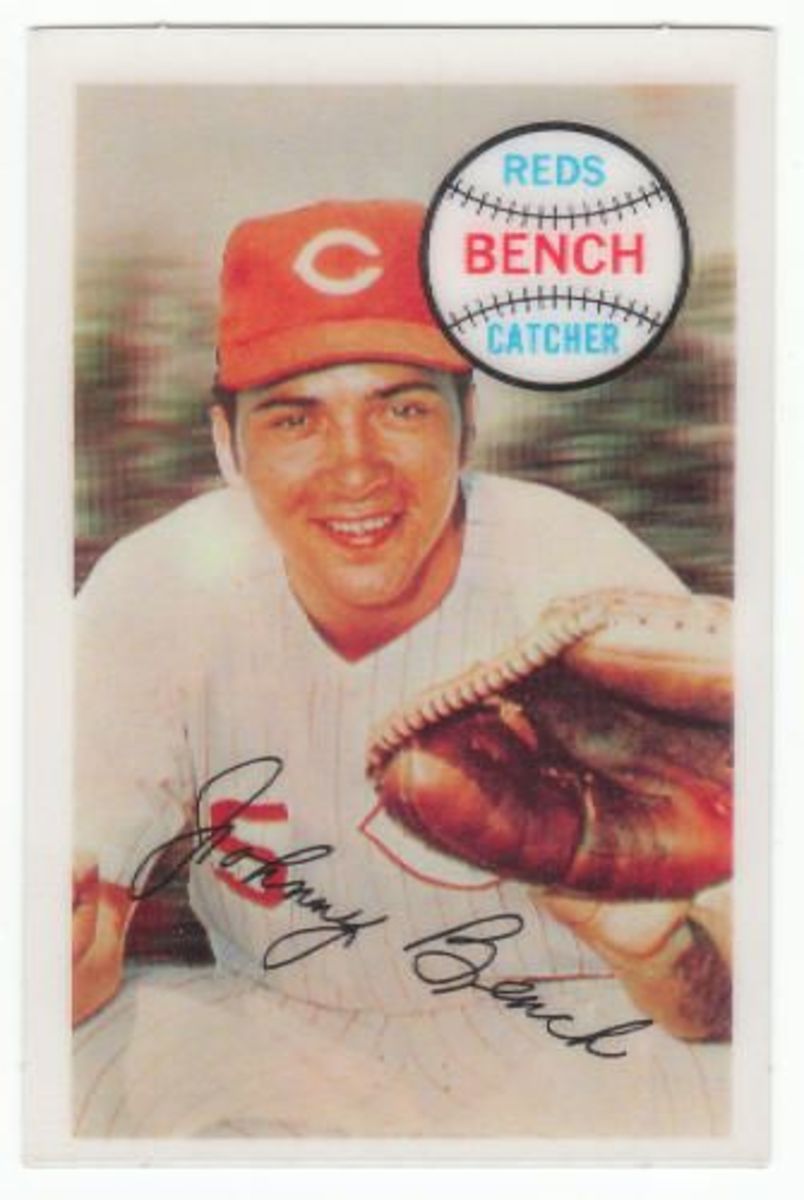

Most years, the worst of the best has 15 to 19 WS. The Cubs’ Travis Wood was the worst of the best in 2013 with 15. The year before, it was Dexter Fowler of the Rockies, also with 15. The last sub-15 team was the 2004 Royals, led by Mike Sweeney’s 14.

But, historically, who is the real worst of the best? Not including shortened seasons and the 19th century, here’s the nine worst, in chronological order.

The 1962 Mets

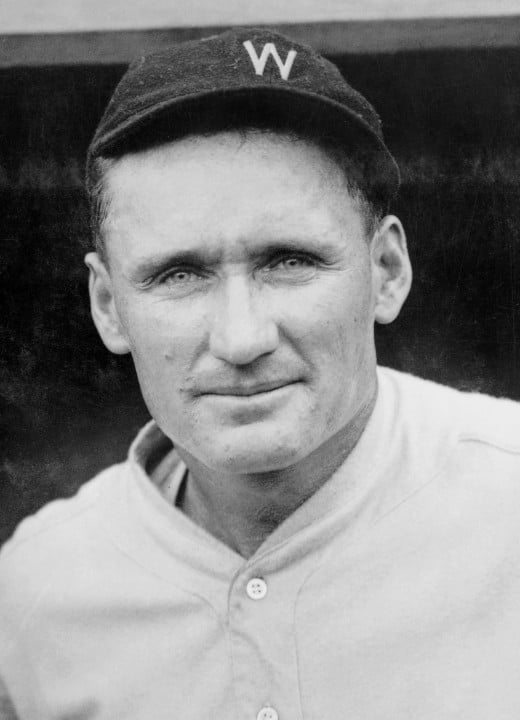

Walter Johnson

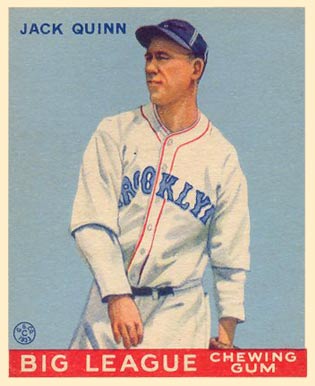

Jack Quinn

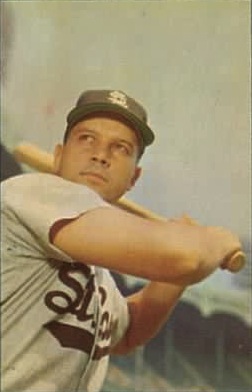

Vic Wertz

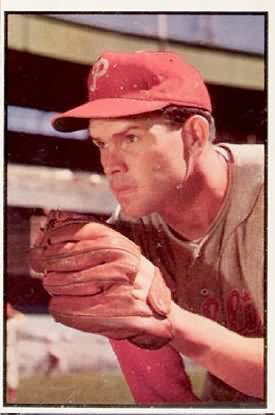

Robin Roberts

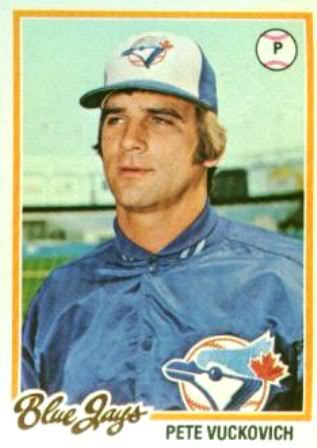

Pete Vuckovich

The Next Worst Bests

Year

| Team

| Player

|

|---|---|---|

1913

| Yankees

| Five players

|

1920

| A's

| Jimmy Dugan, Eddie Rommel

|

1927

| Red Sox

| Buddy Myer, Ira Flagstead

|

1927

| Braves

| Eddie Brown, Bob Smith

|

1932

| Red Sox

| Dale Alexander

|

1953

| Browns

| Don Larsen

|

1955

| Orioles

| Willy Miranda, Gus Triandos

|

1976

| Expos

| Woodie Fryman, Steve Rogers

|

1999

| Marlins

| Bruce Aven, Luis Castillo

|

2004

| Royals

| Mike Sweeney

|

The Worst of the Best

The 1909 Senators: A trio of players led this club, each with 12 Win Shares. One of them, Walter Johnson, is famous for being the best player on many bad Senators teams. Just 21, Johnson was in his second full season for a 41-111 team. He had a 2.22 ERA and 164 strikeouts – very impressive, but not nearly as good as the year before and not nearly enough to overcome the poor support. Johnson went 13-25, the most losses in his career and fewest wins in a full year.

Third baseman Wid Conroy was on the other end of his career. At 32, he was in his first season with the Senators and ninth in the majors. Other than 24 steals, his offensive numbers were extremely underwhelming.

Utility player Bob Unglaub was the third member of the trio. Unglaub, 28, was in his fifth season and third as a regular. Playing first, the outfield and second, Unglaub hit .265 and stole 15 bases.

One problem for the Senators was the lessened output from Long Tom Hughes. He went from 18-15 to 4-7, then pitched in the minors in 1910, winning 31 games. They also traded mid-career star Jim Delahanty, a slumping second baseman. Hughes returned to the Senators in 1911. By that time, Johnson and fellow youngster Clyde Milan were ready to turn Washington around. Milan, an outfielder, turned 23 in 1910, raising his average from .200 to .279. He also stole 44 bases after swiping just 10. In 1912, the Senators won 91 games, the first time they’d even had a winning record.

The 1915 Baltimore Terrapins: If you don’t recognize the team name, that’s because the Terrapins belonged to the two-year Federal League. After a strong first season, the Terrapins collapsed in 1915, going 47-107.

Jack Quinn led the team with 13 WS. Quinn is one of the most interesting players in MLB history. Five years into his lengthy, up and down journey, he was 44-37 when he went to the Federal League. Quinn went 26-14 to lead the 1914 Baltimore team, but fell to 9-22 in 1915, leading the league in losses. He would disappear back into the minors for nearly three years before re-emerging with the 1918 White Sox and going on to win 247 games and pick up 56 saves.

I don’t know quite why the Terrapins collapsed. Quinn struggled, as did the No. 2 starter, George Suggs. As did their third star from 1914, Benny Meyer, who hit .242 before going to Buffalo. In fact, the Terrapins returned all 10 players who had double-digit Win Shares in 1914. Every one was worse in 1915. The team even added the great Chief Bender, and he had his worst year.

The 1928 Phillies: The Phils hadn’t had a winning season since 1917, and this would be their worst year of the sub-.500 streak. With a 43-109 record, Philadelphia had one of its five 100-loss seasons in a 10-year stretch. With 13 WS, the team’s top two players were third baseman Pinky Whitney and outfielder Freddy Leach.

Although his WS total wasn’t that impressive, Whitney had impressive raw numbers in his rookie year. He hit 10 homers, drove in 103 runs and batted .301, receiving some MVP votes. He continued to put up big numbers through 1932, colored by both the high-offense era and small park. Leach hit .304 with 13 homers and 96 RBI. He was then sent to the Giants and continued to hit for a few years.

What happened to the 1928 Phillies? Well, they were a bad team beforehand, and four-time home run champ Cy Williams started to drop off at age 40 in 1928. Fortunately, Phillie fans got a glimpse of the future with a .360 season in limited time for rookie Chuck Klein. Also, the team traded Leach in late October for Lefty O’Doul of the Giants. O’Doul was a 31-year-old former pitcher who hit .316 in his first year as a hitter. Playing every day in Philly, O’Doul enjoyed an amazing season, hitting .398 with 152 runs, 254 hits, 32 homers and 122 RBI. He was second in the MVP voting and had 31 WS.

The 1952 Tigers: Even taking into account shortened seasons, there were only three teams with a leader who had 11 WS in the 20th century. This Tiger club (50-104) was the only one without the excuse of fewer games. Only four players reached the double-digit mark, with first baseman Walt Dropo and outfielder Johnny Groth the leaders and Hal Newhouser and Vic Wertz each with 10.

Wertz was the actual All-Star despite having a half-season’s worth of All-Star value over a full season. Actually, it wasn’t a bad selection – but it does show what was wrong with this team. If you were good, you were traded. Wertz hit 16 homers in 85 games before being traded. In addition to getting rid of an RBI machine, the Tigers traded off their other 1951 All-Star level player, George Kell. At least that deal was early enough to give Dropo a chance to contribute.

Newhouser and Groth played the whole season with the Tigers. Newhouser continued a mediocre string of play (going 9-9) after his great late 40s seasons. Groth hit .284 without power. But, being one of the team’s top players, he was naturally traded after the season along with former All-Star and future 20-game winner Virgil Trucks. Dizzy Trout, another former All-Star, was traded after a few games to Boston, where he put in a serviceable final season.

It would be a few years before the Tigers turned around, but help arrived right away in the form of three stars: Ray Boone, Harvey Kuenn and Al Kaline. Boone arrived in the middle of 1953 and provided instant power at third. Shortstop Kuenn played 19 games at age 21 in 1952 and became the 1953 Rookie of the Year, leading the league in hits for the first of four times. Kaline played 30 games at age 18 in 1953, stepped into a starting role in 1954 and became one of the league’s best players as a 20-year-old right fielder in 1955.

The 1957 A’s: Unlike the teams listed above, these A’s did not lose 100 games. They went 59-94, an improvement of 7 ½ games on the year before. Losing was nothing new to this squad. During their 13-year tenure in Kansas City, from 1955 to 1967, the A’s never won more than 74 games.

The 1956 team was led by third baseman Hector Lopez with 15 WS, the worst of the best for that year. Lopez tied for the team lead in 1957 with outfielder Woodie Held, each at 13.

Lopez, who debuted in 1955, played his fewest games of the 50s, and hit his lowest totals of the decade in runs, hits and homers (11) despite his highest average (.294). Held, a rookie who came over from the Yankees in mid June along with Billy Martin and Ralph Terry, hit 20 homers and hit .239 in 92 games.

Part of the problem was that a few sluggers on the team were a little off their game. Held, Vic Power and Gus Zernial hit for low averages, while Bob Cerv hadn’t yet rounded into form. The team led the league in homers with 166, but had no fully-functional slugger. That changed the next year when Cerv blossomed and Lopez played more. Terry and Ned Garver gave the team two good starters, but there was no relief ace.

So who represented this team in the All-Star Game? Shortstop Joe DeMaestri, who had 9 WS. He hit .245 with 9 homers and 33 RBI. To be fair, he was hitting .288 at the break.

The 1961 Phillies: A few years back, the Phillies became the first sports franchise to lose more than 10,000 games. The 1961 Phillies may not have been the losingest team in franchise history, but no post-World War II Philadelphia squad has quite matched their 47-107 record.

It was also the third straight year the Phils had the worst of the best in the majors. In 1959, it was Ed Bouchee and Gene Conley with 17. In 1960, it was Pancho Herrera and Turk Farrell with 15. In 1961, it was Johnny Callison with 13.

What went (even) wrong(er)? For one thing, they traded three of their previous “stars,” Bouchee, Conley and Farrell. As for the slugging Herrera, his strikeout habit was harder to ignore when his average dropped.

Don Demeter, acquired for Farrell, hit 20 homers in 106 games, but was offensively one dimensional. There were several other fairly well-known names that failed to do much. Tony Taylor, one of the team’s top second basemen ever, hit .250. Future star Chris Short had the worst year of his career, with a 6-12 record, 5.94 ERA and a league-leading 14 wild pitches. As for Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts, it was the most miserable year of his career. Roberts went 1-10 with a 5.85 ERA.

Callison was not only the best thing the Phils had going for them (despite a .266 average and 9 homers), but the young outfielder was on his way to real starhood. Tony Gonzalez also improved, and Demeter found his stroke, batting .307 in 1962, giving the team a solid trio of hitters and building the foundation for the 1964 pennant race.

The team’s All-Star in 1961, though, was Art Mahaffey. He led the league in losses, going 11-19 with a 4.10 ERA. The better offense of the 1962 team helped him go 19-14, and with a 3.94 ERA he jumped from 11 to 17 WS.

The 1962 Mets: No 20th century team has achieved the infamy of the 1962 Mets. They’ve become the byword for bad. The Mets went 40-120 in their inaugural season. The Mets had solid power, but hit only .240. Their only pitcher with an ERA under 4 was Galen Cisco, who pitched four games.

They had two star players, both of whom performed reasonably well, at least outwardly. The Win Shares system does a nice job of balancing out an individual’s performance from the team’s, but I think these two got the short end of the stick because the Mets were so bad. Each was credited with just 12 WS.

Frank Thomas, who averaged 25 homers and 81 RBI for the Pirates and other NL teams over the past nine years, hit 34 homers and drove in 94 runs with a .266 average. His numbers tailed off the next few years. Legendary Phillies centerfielder Richie Ashburn had one last hurrah, hitting .306 with a career-high 7 homers. Ashburn was the team’s All-Star.

It would be two years before a Met would crack the 20-WS barrier, when Joe Christopher, a member of the original team, hit .300 with 16 homers.

The 1965 Mets: The Mets were still struggling a few years later. Christopher was a one-year wonder and Thomas and Ashburn were gone, so they didn’t have any previous star power to fall back on. At 50-112, right fielder Johnny Lewis led the charge with mediocre numbers: 15 homers, 45 RBI and a .245 average. Ed Kranepool and Ron Swoboda, future Mets stars, didn’t do much despite playing fulltime. Of course, they were 20 and 21, so they weren’t ready yet. Tug McGraw was 20, Yogi Berra played his last four games at age 40 and Warren Spahn was 44.

Second baseman Ron Hunt, one of the team’s best players in that era, played only 57 games and had his worst season. He rebounded the next year to be the team’s leader again with 18 – worst of the best for that year, too. It wasn’t until 1967 that Tom Seaver became the team’s second 20 WS player.

Kranepool had the All-Star honors, showing off his 10-homer, .253 form.

The 1977 Blue Jays: The very first Blue Jays team went 54-107. It was the first of three straight to have the worst of the best in baseball. Combining with the 1974 and 1976 Expos, that means Canada had the worst of the best for five out of six years. Woe Canada!

Three Jays had 13 WS each: Jerry Garvin, Dave Lemanczyk and Pete Vuckovich. Right there should be a clue as to what was wrong. All three were pitchers, meaning that no hitter did better than 12 WS. Lemanczyk (13-16) and Garvin (10-18) were unspectacular, but pitched enough innings to contribute some wins. Both were horrific in 1978, then mildly recovered before flaming out. Vuckovich was much more effective, going 7-7 with 8 saves and a shutout. He also had a future, but it wasn’t in Toronto. He was traded to St. Louis, winning 39 games over three seasons before two strong years with the Brewers, including a Cy Young Award, leading the league in wins once and winning percentage twice and appearing in the World Series.

A few of the young hitters went on to successful careers, including Bob Bailor, Ernie Whitt, Roy Howell, Otto Velez and Alan Ashby.

An older hitter, DH Ron Fairly, made it as their representative to the All-Star Game and had a mildly successful year with 19 homers and a .279 average in his next to last season.

A Few More Thoughts

The best of the worst, by the way, was Rogers Hornsby with the 1928 Braves. He is one of two players with at least 30 Win Shares on a 100-loss team. He had 33, and teammate Lance Richbourg had 20. Ron Santo, with the 1966 Cubs, had 30, backed by Billy Williams with his 21.

Brian Giles (29 for the 2001 Pirates) and Irv Young (29 for the 1905 Braves) round out the best of the worst. Young was a rookie that year who went 20-21.

Three teams – including two in one season – managed to have a winning record despite having the worst of the best. The 1924 season was one of the most interesting in baseball history. It was also rather a parity paradise. There were five teams led by a 21 WS player, including the Cubs (81-72) and Reds (83-70). The 1936 Senators were one of two teams with a leader with 21 WS. They went 82-71, while the other, the A’s, lost 100 games.

Two modern teams, besides the 1952 Tigers, managed to be led by a player with 11 WS in a shortened season. The 1919 A’s were led by George Burns -- Tioga George, the first baseman, not his contemporary counterpart with the Giants or the entertainer, who was a few years younger. Burns hit .296 with 15 steals in 126 games. The other was Hubie Brooks in 1981, a Rookie of the Year candidate who hit .307 for the Mets.

The all-time record of 2 WS belongs to three players from the 1884 Union Association, a league that many don’t consider an actual major league. The St. Paul White Caps finished 2-6, led by Billy O’Brien (7-for-30, three doubles, 1-0 and 1.80 ERA over 10 innings) and Jim Brown (5-for-16, four doubles, 1-4, 3.75 ERA in six starts). The Wilmington Quicksteps were 2-16, led by Ed “The Only” Nolan, who went 1-4 with a 2.93 ERA in five starts and hit .273.

Naturally, the only team without a 10 WS player that played 100 or more games was the 1899 Cleveland Spiders, the worst team in the history of pro sports. For this 20-134 abomination, Jim Hughey went 4-30 with a 5.41 ERA. He hit 22 batters and threw 10 wild pitches.