Decades of Baseball Futility

Major League baseball has its storied franchises, the Yankees, the Giants and Dodgers, the Cardinals, and it has other franchises… less storied. Like the Phillies. They made their first World Series appearance in 1915 and didn’t win their first Fall Classic until 1980. And it’s not as if they kept getting there and losing, like the Brooklyn Dodgers. Between 1915 and 1980, the Phillies made just 1 World Series appearance, in 1950, and got swept by the Yankees. It’s almost as if the Phillies were invisible since the beginning of time, or at least since the beginning of baseball.

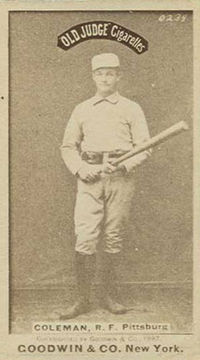

Truth is, the Phillies are older than the World Series. The Phillies began play in 1883. They played 98 games that year, winning just 17 and finishing 46 games behind the first place Boston Beaneaters. The Phillies were led by their 20 year-old rookie pitcher John Coleman who won 12 games and lost 48. John’s winning percentage maybe wasn’t very good but he was a workhorse, tossing 538 innings and he was the indisputable ace of the staff. No other Philly pitcher had more than 2 wins.

The World Series didn’t get going until 1903, so we can’t fault the Phillies for not winning the series in their first 20 years, but what about the next 65? It’s called futility.

Futility? Hello, Senators. They started in the National League and were so bad, they got dropped by the league. Seriously. The league wasn’t doing so good, financially, and it was felt some of the teams weren’t carrying their weight, that is, they were lousy and nobody wanted to pay to watch them and they got booted out of the league. A few years later, though, in 1901, when the American League started play, the nation’s capital was awarded a franchise. The new Senators, sometimes called the Nationals, represented Washington from 1901 to 1960 and they weren’t very good either, although they did win the World Series in 1924 and on the arm of Hall of Famer Walter Johnson, who went the distance in Game 7, a 12 inning, 4 to 3 Senators’ win. There wouldn’t be another extra inning World Series Game 7 until 1991, won by the Minnesota Twins, who, prior to 1961, were known as the Washington Senators. That’s right, the Senators jumped to Minnesota and wouldn’t you know it, almost as soon as they got out of Washington, they started playing some pretty good baseball.

Which is not to say the Senators didn’t provide some memorable contributions to baseball history. Take that game in May of 1901, their first year in the American League. The Senators were leading the Cleveland Blues by a score of 13 to 5 and with Cleveland batting in the ninth inning and with 2 outs and nobody on base, the Blues rallied, scored 9 runs and won the game, 14 to 13. And they call it the dead ball era. That same year, 1 of the Senators’ players was Dale Gear, a pitcher-outfielder who compiled a .232 batting average and an E.R.A. just over 4. Not too shabby for a player who was…a woman disguised as a man. Only Dale and her manager knew and since both had promised never to tell, Dale’s secret has never got out although Dale’s family has kept it alive for more than a 100 years and some serious baseball historians believe it’s true.

All those years of futility didn’t mean the Senators didn’t have some pretty good ballplayers. They had Johnson, whose 417 wins rank him second all-time behind Cy Young and for a short while, they had another Hall of Famer, “Big Ed” Delahanty. Big Ed was the best of the Delahanty brothers – 5 siblings, all men, so far as we know, Ed, Frank, Jim, Joe and Tom, played major league baseball. Take that, Alous. Big Ed played nearly his entire career with the Phillies and while with the Phillies, became only the second major leaguer to hit 4 homeruns in a single ballgame. Pretty impressive, even more impressive, or less impressive, all 4 of the homers were inside-the-parkers. Alas, the Phillies being the Phillies, lost the game, 9 to 8.

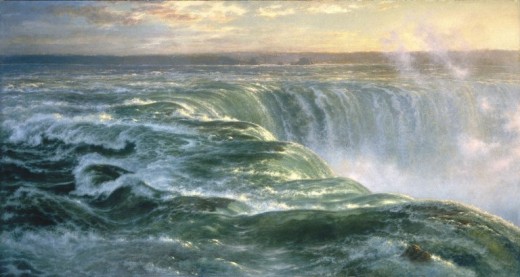

In 1902 and with 14 years in the bigs, Big Ed went over to the Senators and hit .376. In July of the next year and hitting .333 and with the Senators thinking they’d got themselves a pretty good ballplayer, Big Ed became the first major leaguer, and so far as I know, the only major leaguer, to go over Niagara Falls. Seriously. It wasn’t a stunt. He didn’t have a barrel or a tightrope or a life preserver and he didn’t survive. Mystery surrounds Ed’s death. Was it suicide? Murder? What’s clear is it was nighttime, the Senators were traveling by train and Ed was, uh, boisterous, and the conductor kicked Ed off the train. Ed started walking and crossing the International Bridge, ended up somehow in the river below.

The 1950s were a miserable time for the Senators. They couldn’t get out of the second division and it was the Yankees most dominating decade, pennants and world championships galore, and then, in the middle of the decade, out of nowhere, well, actually out of a fictional Hell, the lowly Senators rose up and vanquished the mighty Yankees. Hurray for the Senators! Too bad it was all make-believe. It was Damn Yankees, a book, a Broadway play and a movie. It was Faust, American-style. A long-suffering Senators’ fan can’t take it anymore and after another loss, he gets up out of his chair in front of the TV and cries out, anguished, for a power hitter. The Devil (Ray Walston of My Favorite Martian fame, in both the Broadway and movie versions,) arrives to provide the power-hitter and it’s the middle-aged guy himself, who sells his soul right there in the living room and becomes Joe Hardy and leads his Senators to the pennant. (We don’t know how they did in the series, probably lost.) It’s a long and convoluted plot, Ray and his beloved wife sojourn in Hell and are disaffected and ultimately, happily reunited at the end and there’s no shortage of bad guys, including a magnificent vamp with a drop-dead sexy signature song – Whatever Lola wants, Lola Gets.

16 miles south of Washington, D.C., is Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home and burial place. Richard “Light Horse Harry” Lee, Washington’s favorite cavalry officer and the father of General Robert E. Lee, eulogized Washington at Mount Vernon in 1799, and in words that have become immortal:

“First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Vaudeville comedians putting their own spin on Lee’s words, immortalized Washington too, the ball club, not the father of the country, and in words that would rankle the team and the city for a very long time:

“First in war, first in peace, last in the American League.”