Adam Ondra Climbs Back to the Top

Rock climbing can be a fickle sport. Some days you have it, some days you don’t. Some days a climber may flash every boulder or lead route they attempt. Other days a climber may be unable to top any route, let alone complete the first move. Most days, an athlete is somewhere in between, topping routes that fit their skillset and struggling with problems that are out of their comfort zone. This is true at every level of the sport, from the local gym with weekend warriors to the international level with world class athletes.

A Blossoming Rivalry

On August 10th, Adam Ondra entered stage left at the IFSC Climbing World Championships in Hachioji, Japan with the spotlight squared on him. Just a few minutes prior, Ondra heard the crowd roar as he was sitting in the backstage holding area, awaiting his turn at the first boulder of the Men’s Bouldering Final. Tomoa Narasaki had just earned the first top of the final on a problem that had perplexed the four previous finalists. Narasaki entered the World Championships on an impressive run of form in 2019 IFSC bouldering competitions, including one World Cup Championship at Wujiang and three second place finishes. His most recent second place finish at Vail in June catapulted him past Ondra for the world number one ranking.

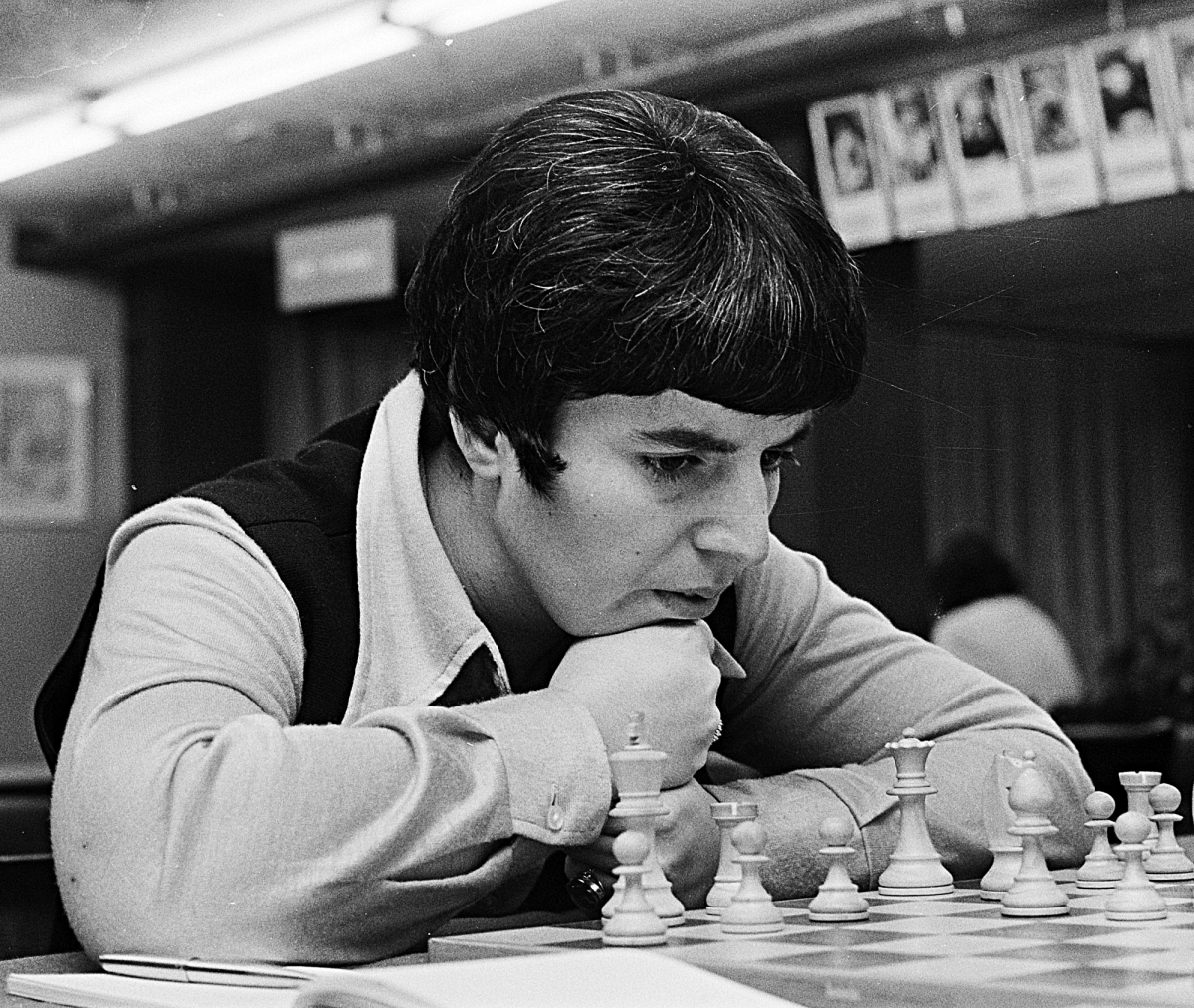

Ondra, widely considered the best all-around competition climber in the world with his number two ranking in bouldering and number seven ranking in lead climbing, had a more sporadic start to his 2019 bouldering campaign. He started the season strong with a World Cup Championship in Meiringen, but since struggled to two seconds, a fifth, and a fourteenth place finish. Despite this, only five points separated Ondra and Narasaki in the world rankings entering the competition. They were the two favorites, and all eyes were on Ondra following Narasaki’s top. Ondra waved to the crowd, jogged up to the front of the wall, and chalked up his hands for the first of four boulder problems. His four minutes to top the boulder had begun.

The World's Best Compete

The IFSC Climbing World Championship is the pinnacle of competition climbing and typically held every two years as a celebration of one of the fastest growing sports in the world (The IFSC recently decided to switch from an even year schedule to an odd year schedule, resulting in the World Championships being held in both 2018 and 2019). The event hosts men’s and women’s events over an 11 day span in three climbing disciplines: lead climbing, bouldering, and speed climbing. Top climbers from all over the world enter the event, including Austrian Jakob Schubert (#1 ranked male in lead climbing) and women’s climbing powerhouse Janja Garnbret (#1 ranked female in both lead climbing and bouldering).

Ondra was no newcomer to the competition, having first competed as a 16 year old in the lead discipline at the 2009 event in Xining, China. Since then, Ondra has racked up two golds, one silver, and two bronzes in the lead climbing and one gold and two silvers in the bouldering, making him one of the most decorated climbers in World Championship history. Narasaki on the other hand, was relatively new to the World Championships, having first competed in 2014 as an 18 year old and winning his first and only Bouldering World Championship in 2016. Narasaki was on an impressive run throughout the season though, and no stage in the sport was bigger for the two heavyweights to compete.

From Best to Sixth

Ondra measured up the boulder problem that had confounded the four climbers prior to Narasaki. The problem did not match up well with Ondra’s traditional, static skillset, instead presenting a more modern, dynamic route. The problem opened with a run up start requiring a left hand sloper grab with a simultaneous left foot plant and right toe hook catch. The next move was a physical double dyno to a vertical left foot half volume and a left hand jug. To gain the zone, climbers reached up for a left hand undercling and moved their right foot up to a horizontal volume. The final move required climbers to find enough friction on the sanded wood volumes to push up to the final volume for the top.

Narasaki was the only finalist of the first five climbers to solve this move, with the others falling off while reaching up. Ondra, the top semifinalist and the last of the six finalists to climb, took a step back from the wall in preparation for the run up start. With his long, spindly legs, Ondra took two quick steps up to the problem and jumped, briefly catching the left hand sloper but missing on his right toe hook. His second and third attempts yielded similar results for the second ranked boulderer in the world. Finally, two and a half minutes into his allotted time, Ondra stuck the toe hook and was on the wall. He squared up for the double dyno and effortlessly traversed through the air to the left foot volume and stretched for the hand hold. A gasp erupted from the crowd as he missed the left jug and fell off the wall. Back to the start.

After a short break to reconsider the route, Ondra walked back up to the wall. One and a half minutes left. He took a step back. Run up to the wall. Miss. Reset. Run up to the wall. Miss. And again. And again. With one minute remaining, visible frustration began to set in for the typically laser-focused Ondra. Run up, fall. Run up, fall. An awkward air filled the arena as the world’s best climber was flummoxed by a first set of moves that the five other climbers breezed through. With thirty seconds left, Ondra began desperately throwing himself at the wall, hoping something might catch for him to start his climb. Scant yells were heard from the crowd urging him on. With seven seconds left and not enough time remaining for Ondra to make a full attempt at the boulder, he grabbed his chalk bag and mustered a half-hearted wave to the crowd. Head down, he mercifully walked off stage to the holding room. No zone. No top. A lot of work to do to catch Narasaki. The wall had won.

The final three boulders yielded similar results for Ondra, all ending in frustration and the same half-hearted wave to the crowd as the first boulder. Incredibly, he finished in sixth place out of the six finalists, with no zones and no tops. It was without a doubt the worst performance of his career; Never before had Ondra been so thoroughly defeated by a bouldering wall. Narasaki finished first, dominating the competition and clinching the championship on the third of four boulders. His performance featured four zones and two tops, the only two of the entire men’s final. It was a display of pure climbing domination by Narasaki and an utterly shocking performance by Ondra. Narasaki’s lead in the rankings ballooned from five points to seventy-nine points over second ranked Ondra. The gap seemed much wider though.

Back to the Top

But climbing is a fickle sport. Some days you have it, some days you don’t. Five days later, Ondra won the IFSC Lead Climbing World Championship with an impressive 34+ score in the final, edging out the number one ranked world lead climber Alexander Megos by one hold. Narasaki, ranked thirteenth in the world lead climbing rankings and just beginning to dip his toes into lead climbing, fought to a fourth place finish with a score of 30 in the final.

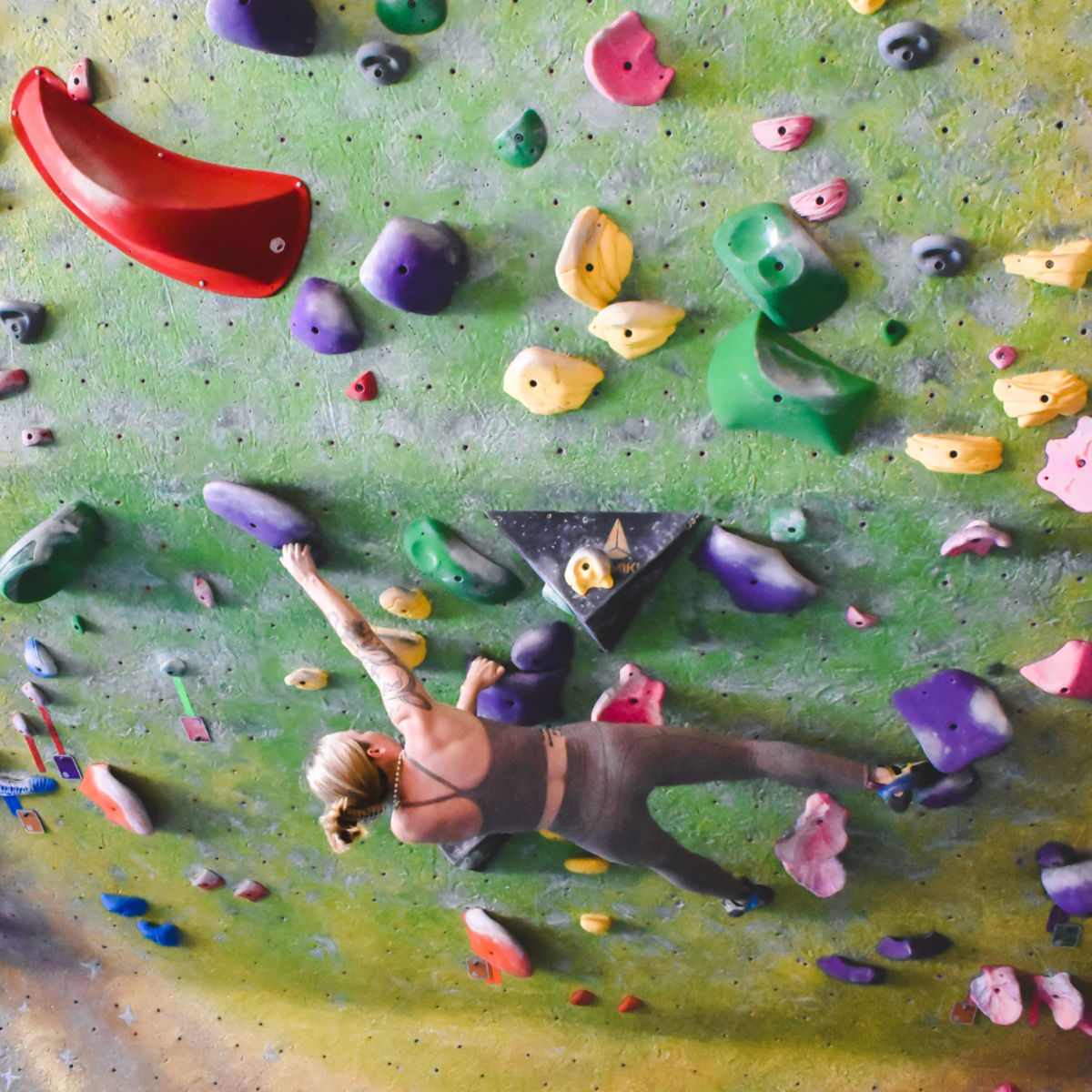

None of the seven other finalists were as clinical as Ondra on the day, though. Ondra rediscovered the creativity that he has come to be known for and that he lacked in the men’s bouldering final. He climbed fast and precise, measuring up each hold quickly and taking little time for breaks. He was focused. His winning move came on the final right-to-left traverse of the championship route, featuring unimaginably small sideways crimps and awkward triangular volumes jutting out from the wall. Ondra, after moving quickly throughout the route, had finally showed signs of fatigue as his arms flexed up to a 90 degree angle, fingertips clinging to the tiny crimps. His time left on the wall was limited. In a final move of desperation, Ondra threw his left arm out to hold 34, catching it before losing his balance reaching for hold 35. He fell down from the wall in first place, a lead that would not be relinquished to the three climbers remaining.

Just five days after his most disastrous climbing performance of his career, Ondra fought back to the top of the competitive climbing world. As his name was announced as World Champion, Ondra allowed himself a brief celebration, screaming and shaking his fists, half relieved and half ecstatic for his win. He was Adam Ondra again.