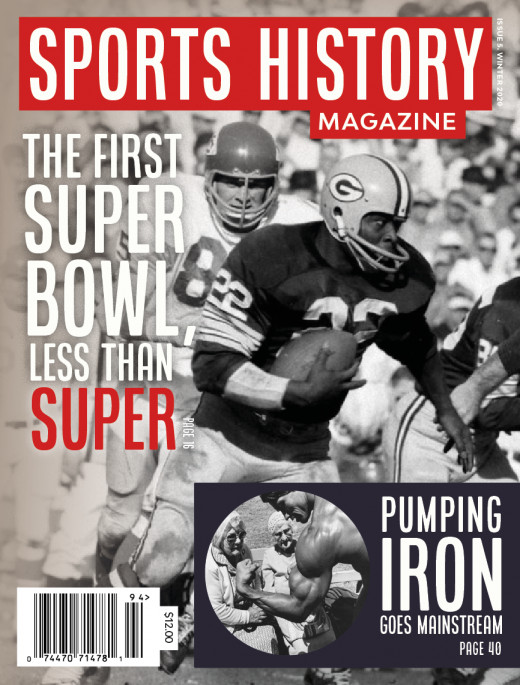

The First Super Bowl, Less Than Super

Officially called the “AFL-NFL World Championship Game”, the first Super Bowl match was little more than an inconsequential game fought between two bitter league foes, the established National Football League (NFL) and the younger American Football League (AFL). Dating back to its origins in 1920, the NFL had managed over the decades to fend off a revolving door of competing leagues, most of whom ran into financial problems before they could seize a slice of the pro football landscape. But starting in 1960, a reincarnated AFL that was bankrolled by the son of a Texas oil tycoon began to nip at the heels of the NFL. Six years later, the AFL would succeed in forcing a merger with its big brother, creating a single football behemoth with two conferences. Their inaugural faceoff on January 15, 1967, a clash of owner egos and league loyalties, became the launching pad for the Super Bowl.

It was on a summer evening in 1966 that the AFL and NFL announced their merger to the public. Team owners from both leagues negotiated the deal and commissioner Pete Rozelle endorsed it. The NFL and its traditional supporters at media outlets such as CBS and Sports Illustrated finally gave way to pressure emanating from the deep pockets of Lamar Hunt and his wealthy franchise cohorts. A businessman and heir to his father’s oil fortune, Hunt had coveted but was denied an NFL team of his own. He subsequently went off and launched a new league, which opened up new football markets where the NFL was absent, such as Boston (Patriots), Buffalo (Bills), Denver (Broncos) and Houston (Oilers).

By 1965, the upstart league was boasting 8 franchises and a $36 Million, 5-year TV contract with NBC.

While the older NFL was outdrawing the AFL in gate receipts, the AFL was able to outbid its rival for talent on the pitch. College stars like Alabama’s quarterback Joe Namath joined the New York Jets for a record $427,000 and USC’s Heisman Trophy winner Mike Garrett shunned the NFL and ended up with the AFL’s Kansas City Chiefs. By 1965, the upstart league was boasting 8 franchises and a $36 Million, 5-year TV contract with NBC. The actual merger wouldn’t crystalize until 1970 when the term ‘Super Bowl’ would also emerge and the iconic roman numerals would start appearing. But until then, as part of the arrangement, the two football organizations agreed to hold an annual match between the champions of each league. The first winning teams to take the field were the Green Bay Packers (NFL) and the Kansas City Chiefs (AFL).

Tensions ran high as the day of contention was approaching in the early winter of 1967. Not only had the Packers and Chiefs never played each other before, but Lamar Hunt, the founder and force behind the AFL, was also owner of the Kansas City Chiefs. Led by their head coach Hank Stram, KC posted a record of 11-2-1 and beat the Buffalo Bills 31-7 to receive an invitation to play at the inaugural AFL-NFL World Championship Game. The Packers finished their season 12-2 and were coached by the venerable Vince Lombardi who never experienced a losing season in the pros.

At stake was more league politics and ego than fan enthusiasm and individual team trophy.

Before Lombardi joined Green Bay as their head coach in 1959, the franchise had posted an NFL worst record of 1-10-1. The future Hall of Famer turned the team around and secured 4 NFL titles by the time they faced Kansas City. Despite the Packers being favored by 13½ points, Lombardi and his dynastic squad were under enormous pressure by the NFL to outperform Lamar Hunt. At stake was more league politics and ego than fan enthusiasm and individual team trophy. Almost as an after-thought, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum was hastily picked six weeks earlier as the venue for the match. Tickets for the AFL-NFL showdown ran between $6 and $12, but only 2/3 of the stadium’s 93,000 seats were filled. More spectators had shown up a month earlier to watch the Packers take on their hometown LA Rams. The 75-mile radius TV blackout around Los Angeles also angered fans who found the top-tier tickets too expensive and refused to attend.

Having played in separate leagues with some nuanced differences, the league adversaries showed up on game day with their own balls. Kansas City used the AFL’s narrow and ¼ inch longer Spalding football that threw better, while Green Bay played with the NFL’s fatter Wilson ball that was more kickable. While the head referee was an NFL veteran, the rest of the officiating crew was comprised of a combination of NFL and AFL referees. Both leagues were also followed by their broadcasters, a media rivalry in its own. CBS telecast the NFL and NBC covered the AFL. On the ground, their TV trucks were even separated by a fence as they simultaneously transmitted the game to their respective audiences.

Assigning little importance to the game itself or the value for posterity, both NBC and CBS deleted their tape footages of the match.

The Packers ended up winning the game 35-10. Len Dawson, Chiefs quarterback who led both leagues the previous years in scoring passes, managed only one touchdown throw with 16 of 27 completions and 211 yards. The Packers’ Bart Starr earned the game’s MVP award with 2 touchdowns and 16 of 23 successful tosses on 250 yards. By the time it was all over, Lombardi’s Packers played a better game but the spotlight was on the NFL, which emerged triumphantly in the inter-league battle for football supremacy.

Assigning little importance to the game itself or the value for posterity, both NBC and CBS deleted their tape footages of the match. It was common practice in the television industry back then to re-use tapes because of the high costs of procuring new ones. With the help of NFL Films, it wouldn’t be until 2016, or 49 years later, when all the available film fragments were finally sourced and stitched, and the epic game remastered in its entirety.

Subscribe to our beautiful glossy magazine through SportsHistoryWeekly.com

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2020 Gill Schor