Why Are People Drawn to Risk?

Let me clarify at the outset that I am now 75 years old and, at this point in life, the greatest risk I face is spilling my coffee.

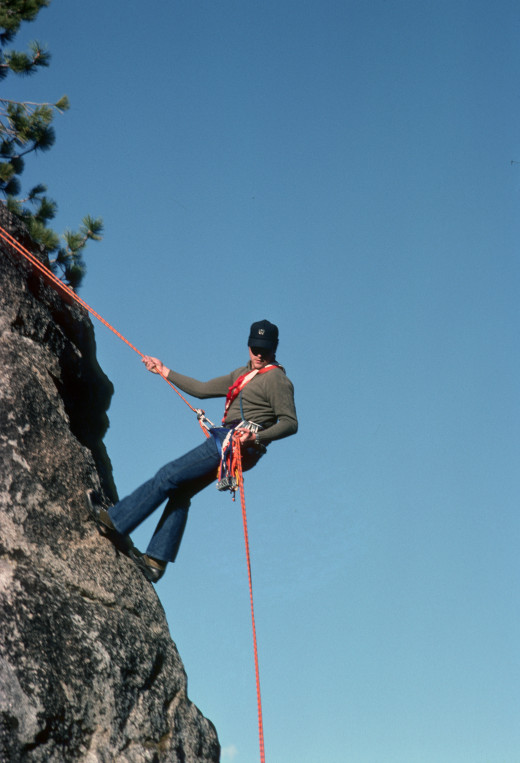

When I was younger, I was a U.S. Marine and served with 1st Marine Division ground forces in South Viet Nam in 1966-67, and I consider my time as a Marine some of the most educational years of my life. I made my first sport parachute jump in March, 1968, while still on active duty, and continued skydiving until November, 1992. I was a technical rock climber during the ‘70s, but managed to break the right ankle on a traverse in March, 1979. Currently, I am PADI-certified as a Rescue Diver, and I continue to dive during the warmer months and on vacation. Briefly, I am acquainted with risk.

I think every individual responds to risk with a slightly different perspective. What may be regarded as foolhardy and pointlessly hazardous for some may merely be another learning experience for another. Simply stated, “risk management” is a life-threatening situation for some, but a challenging exercise of learning a new skill for others. Clearly, ATTITUDE is important. Those who extend themselves in elevated risk environments or situations are not necessarily “adrenalin junkies”.

For many who aspire to skydive, the issue is not, “Can I do it?” Having seen others do it, the question becomes, “Can I learn to do this properly?” Such a person manages risk through training and preparation. This person must objectively assess, “Do I have the skill set, the tools, the talents needed, to do this safely and enjoyably?” If the answer is unclear, the next question is “Where and how can I train to do this?”

Someone brighter than I (I believe it was Brian Germain in his book, “The Parachute And Its Pilot”) commented, “The brave may not live forever, but the cautious do not live at all.” The question develops, how do we define or enrich our life? What makes it exciting or fun? What challenges us to reach further?

My father was a bold young man in a tough metropolitan environment but, from his parental perspective, he saw no point in risk without reward. He witnessed a few of my jumps as friends and I worked together in freefall and commented, “Why are you trying to kill yourself?” I explained that my jumps and other activities were a celebration of Life, not a hedonistic, thrill-seeking death wish. There is a progression in skydiving, and I enjoyed each level of that development as well as the exercise of the techniques I’d learned.

His next question (predictably) was, "What if the parachute doesn’t open?” I explained that I was prepared for that through training and practice. I open my main at the prescribed altitude, and altitude provides time to quickly assess the situation, release my malfunctioned main canopy, then deploy my reserve canopy. That process takes only seconds. None of my answers satisfied him. Two of my jumps (1970 and 1974) did require reserve deployments. I traced the problem to human error and modified my packing procedure. The remainder of my jump activity, over the next 18 years, passed without another malfunction or a reason to deploy a reserve.

Skydiving was, in a sense, a therapeutic way to adjust my perspective. If work was stressful, unstable or unpleasant, then a skydive would distance me from these earth-bound issues. At 12,500 feet, my focus was on the next three minutes of my life – 60 seconds of freefall, a clean main canopy deployment, and about two minutes of maneuvering my canopy to target for a good landing. Nothing else, nothing less mattered. It was a mini-vacation or distancing from mundane aggravations.

Anyone who looks out the door of the aircraft on their first jump is going to nervously question their decision and, for some, it’s a religious experience! We’re all aware of the fight-or-flight response to fear, but there’s a third possibility: freeze. We’ve all heard of the “deer in the headlights” response, a creature immobilized by fear. That is not typically a successful response for the deer, and it’s often life-threatening for the motorist who reflexively tries to avoid the creature and sails off the highway. As a jumper, you are constantly thinking and reacting.

In the ‘70s, before accelerated freefall training and tandem jumping was an option, I was a jumpmaster at a northeastern paracenter. The jumpmaster takes wind conditions and canopy performance into consideration and chooses the exit point at altitude for student parachutists to leave the aircraft. Two adults (on different occasions, a few months apart), one male and one female, froze in the door on their first jump. Understand, this is not a tactical environment; this is a sport paracenter and these students are there on a voluntary basis, paying to make a recreational jump. They are certainly permitted to change their mind.

In both cases, I assisted the jumper back into the aircraft, then helped the other student jumpers in the aircraft to exit. Having witnessed the exit of the other students, I again asked if the jumper if he/she was ready or willing to jump. The young woman reconsidered, exited as instructed, and her (static line) jump was successful. We discussed it later, and she returned to jump again and advance as a sport parachutist.

When given the same opportunity on his flight, the gentleman shook his head for a negative response. Shortly after we landed, I asked the gentleman for his perspective, and he candidly admitted that the sight of the drop zone from the door at 3,000 feet was enough to dissuade him. I understood and encouraged him to observe the jump activity from the ground for the rest of the afternoon to better reassure himself that the equipment worked reliably, and perhaps to go through the FJC (first jump course) again, without additional charge. I don't believe he returned.

A sport parachute jump is not a rite of passage; there’s nothing to “prove”. The choice not to jump indicated to me that the training did not adequately prepare these students for their jumps. Their questions were not answered, their concerns were not resolved. That’s a training issue, not a character flaw. I later discussed the situation with his instructor, and asked if he thought the gentleman was “ready”, and his answer was vague, ambivalent. He was under pressure to cycle the class through. The instructor’s job is to train student jumpers, to give them the knowledge and confidence to make them ready for the jump. In weeks to come, the young lady returned to jump, but I never saw the gentleman again.

In my opinion, a person who trains to jump but changes their mind in the door of the aircraft has not been properly or adequately trained to cope with the very rare malfunction, has not been given the confidence to leave the aircraft, steer the canopy, land properly and complete the jump. I continued as a jumpmaster but changed my priority to ground instruction to better prepare student parachutists to exit properly, to assume a good face-to-earth position, to check that their canopy is fully and properly deployed, to steer their canopies to a target area and to execute a good parachute landing fall (PLF) to avoid injury on landing.

In training for any elevated risk activity, we must learn never to panic or allow fear to immobilize us. We must think our way out of a situation, and keep processing. Do something, even if it’s the wrong thing to do because it may work successfully but, if we do nothing, we will sentence ourselves to injury or death. Elevated risk activities require us to responsibly prepare ourselves, to train properly and execute promptly.

Years ago, Charles Heal, a gentleman I respect, taught his class the "OODA Loop", to Observe, Orient, Decide and Act, and to consciously repeat the process continually as more information becomes available. I was in that class, and these are lessons for life. People risk because to live without it is not to live at all, but simply to exist.

My wife made five static-line jumps before we were married, and I was genuinely impressed. We've been married for 40 years, and I'm still impressed. She was curious about jumping, satisfied that curiosity, and pressed on to other things. Landings with the modified military 28- and 35-foot canopies we used for student training in those days were often "brisk". That situation has since noticeably improved.

Years have passed since then, and our daughter and son have grown; they both made tandem jumps, primarily because they were curious about it. I did not encourage or discourage their plan to jump because I respected their independent decision to satisfy their curiosity. Very clearly, curiosity is a factor for risk-takers. I'm glad my daughter and son have a spirit of adventure, and I remain proud of them. Have you ever asked, “What would it be like to jump/fly/climb/dive/ride?” We all have curiosities, and if that fuels your desire to reach a bit further than most people to answer your questions, then proceed intelligently, train well, function carefully and press on.

As a jumper, trust in the canopy’s reliable deployment is a development that may take 10-20-30 jumps (depending on the jumper's frequency of activity) before a novice skydiver leaps out the door without significant concern, confident of good canopy deployment. Licensed jumpers are permitted to repack their own main canopy (only a federally certified rigger may repack a reserve), and many jumpers repack very carefully, confident in their own packing procedure but concerned about others repacking their main canopy. A skydiver takes little for granted because the jump is not over until you walk off the field. In other words, simply because you have a fully deployed canopy, you still have to land. I think many people jump because they want a life without guarantees, they want to be in control of their own fate and they have the self-confidence to deal with unexpected situations.

There are four aspects of skydiving that I enjoyed and appreciated: (1) freefall relative work or R/W, i.e., working with other skydivers in freefall to transition from one formation to another, (2) freefall photography, capturing images of other skydivers in freefall, (3) working with student parachutists and (4) I enjoyed the friendship and camaraderie of other men and women in my skydiving community.

When we operate in a completely unfamiliar environment or attempt a different task with a steep learning curve, it is normal to experience fear. Do you remember your first driving lesson? On my first jump, I was excited but ready to go; however, on my first flying lesson, my knees were shaking! As we taxied for takeoff, I handled the yoke of the Cessna 150 as if it was an automobile’s steering wheel (big mistake) and was incredibly clumsy with the controls. In other words, I was not a “natural”. On the contrary, I was a flight instructor’s nightmare. Those first landings were white-knucklers for me, I assure you. These things wear off as we become familiarized with the controls and the tasks at hand, and that development or learning process is a great part of what drives risk-takers, because it expands personal horizons.

It has been my privilege to witness remarkable acts of courage, but I’ve never met any well-adjusted person who is “fearless”. I’ve met a number of people who control their fear instead of allowing it to control them. The pattern of confronting what frightens or challenges us builds what I often refer to as a "moral muscle". If we can deal with small challenges and cope with progressively greater ones, I believe it significantly contributes to the quality of life.

The requirement is to train well, assess risk carefully and equip ourselves properly with quality equipment to accomplish the tasks. If we can recognize what is clearly beyond our skill set or level of training and we've provided ourselves with an extraction strategy, a method of withdrawing without additional risk, we do well to exercise our best judgment without stumbling over our ego.

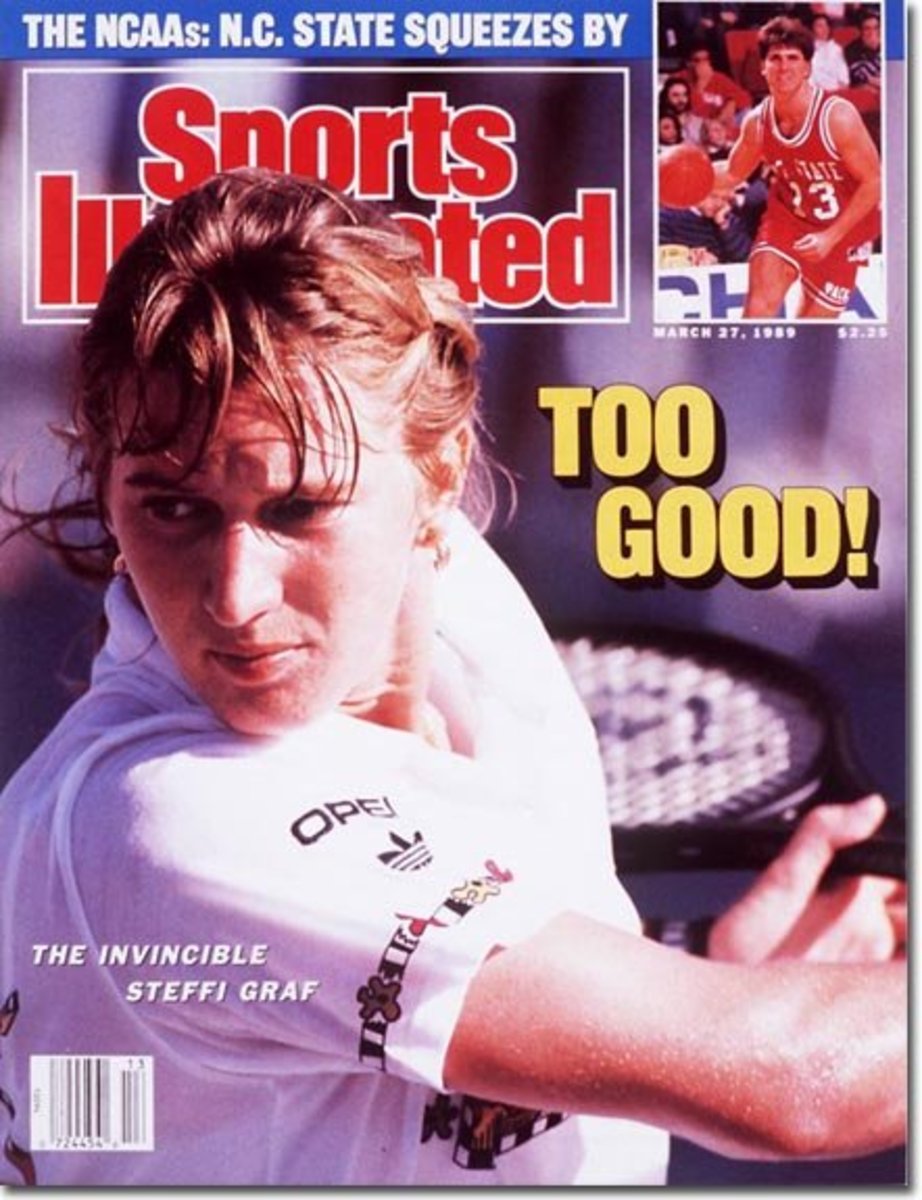

As a rockclimber, I’ve found myself clinging to a rock face like a human fly with no other handhold or foothold in reach. Yes, I was frightened. What are my choices? Shall I remain on the rock indefinitely? If you’ve followed safety procedures by placing protection or hardware into the rock and have a trusted climbing partner anchored on the other end of the rope, you may reach for the next handhold and, in doing so, you may take a fall; that’s what the rope is for, and that’s why we climb as a team.

Technical climbing is not to be approached lightly. Anyone pursuing this interest should seek well-qualified instruction in rockcraft and learn how to effectively use the rope and hardware associated with climbing (carabiners, hexnuts, chocks, cams, etc.). Rock climbing is physically demanding. Occasionally we encounter rocks we can’t climb, traverses we can’t make, summits we can’t reach. In other words, sometimes the rock wins. There are lessons there as well.

Many people are apprehensive when it comes to firearms. They are concerned about accidents, recoil, loud noise, and all of that is understandable. It is understandably stressful for a young man or woman to become familiarized with firearms, especially handguns (pistols and revolvers), but there is a progression or process involved. If we address the basics thoroughly, carefully, and strictly adhere to the principles of firearm safety, then the firearm does not pose a threat to us.

A firearm is a mechanism, a device with no will or malevolence of its own. Its potential for harm is immense, and I can certainly say the same for an automobile; however, if we learn how to use it properly, it is no more difficult to use or hazardous to us than a power tool, and I am very respectful of the capabilities of all power tools, I assure you, so that is not my intent to minimize or trivialize the risk of handling a firearm badly. Again, training is key. Regular practice will build on that training to provide a level of competence, and that is an individual responsibility.

The instructor’s responsibility is to provide a qualified working knowledge of his subject, an appropriate, supportive environment for instruction, and sufficient guidance for a baseline of safe conduct on (and off) the firing line. It upsets me to see male ego cloud better judgment when a husband attempts to teach his wife (or a father attempts to teach his youngster) how to shoot with the presupposition that he knows how to teach. We have to LEARN how to teach.

For someone who is claustrophobic and/or not comfortable in water, scuba diving may be an intimidating concept. There is nothing so basic to our survival instinct as breathing, and the thought of being immersed in water, surrounded by it, is very frightening to more people than we suspect. Those who are unfamiliar with scuba regulators are unlikely to trust them implicitly, but this is what we breathe through as we dive. It doesn’t take long to generate trust in the regulator, but it’s a psychological barrier for some people. How is that best addressed?

For someone who is interested in scuba but uncomfortable with immersion in water or the threat of suffocation/drowning, what overcomes a barrier like that? Well, initially using a regulator in the shallow end (waist or chest deep) of a swimming pool, then easing into the deeper end that still permits prompt, unhindered access to the surface air. It really doesn’t take long to realize the regulator will deliver air reliably. Good training is a fine foundation, and there are many classes available to the certified diver to continue developing skills and knowledge. Confidence developed through practice and experience makes a great difference.

We use analog or computer-integrated gauges that display all the parameters we rely on – remaining air pressure in our cylinders, depth, time, a compass for direction, water temperature, etc. Underwater computers can calculate how much time we may remain at a depth and provide all other necessary information. Imagine taking a road trip without a fuel gauge. What would preoccupy your thought process? Lacking an indication how much fuel you have left, you’d be very concerned when your fuel would run out, so a reliable fuel gauge would relieve considerable stress.

In much the same way, the gauges we normally use today provide us with all the information we need for a safe dive. How much air remains in our cylinder? How deep are we? In what direction are we moving or wish to move? The exercise of good judgment and the lessons we’ve learned as we certified as divers will carry us through, and additional training and classes would advance and enhance our dive experience. There are different certifying agencies (PADI, NAUI, SSI, etc.) and I hesitate to recommend one above the others. Of greater importance, whatever the agency, is the relationship to the instructor.

My son, at his request, was PADI-certified as a diver at age 14. You may be certain I would not expose him to elevated risk if I didn’t think he was psychologically capable of following instruction and responsive to training. My son was the youngest student diver in that class. He did a fine job, and the adults were encouraged, thinking, “If he can do it, I should be able to do it!” Today, that young diver is 30, has completed a 5-year enlistment with the U.S. Navy and is a fine police officer. He's too busy with his work, and being a father to embrace diving at this point, but he may return to it someday. That is his choice.

Anyone who claims never to have experienced fear has led a very sheltered life, is in denial or is simply a liar. We fear what we don’t understand, can’t predict or can’t control. I have seen good Marines who conducted themselves boldly in life-threatening situations but were frightened of spiders or snakes. I know people who I deeply respect who would rather face an armed assailant than speak in public. Ask any parent if they are fearful when they hear a screech of brakes while their youngster is outdoors playing but out of their sight. Yes, everyone experiences fear. Just as we are fearful of different things, we respond to challenges or risks differently.

We have to assess what constitutes “justifiable risk” or reckless behavior. A man jumps into a swift current and is swept downstream at considerable threat to life and limb. If he did this to save another person or to rescue his dog, we applaud his courage. If he did it because he dropped a 6-pack of beer in the water and he’s trying to retrieve it, we have to say he’s a fool. The goal or objective has to justify the risk.

Understand that there’s a difference in the perception of risk. Accept that good training and preparation minimizes risk, so we do well to seek out and accept the best training available. Once trained, build upon that training while reviewing the basic safety procedures. Avoid complacency, because it is dangerous. Never forget what it was to be a student or novice, review the basics regularly, and help others in their learning process.

May your curiosity be more than matched by your sense of adventure!