Why is Bodybuilding a Form of Prayer?

References

Sartre, Jean-Paul. The Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. Edited with Introduction by Robert Denoon Cumming. Vintage Books (Random House). New York, 1965

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Essays in Existentialism. Edited with foreword by Wade Baskin. Citadel Press (Kensington Publishing Corp). New York, 1965, 1993.

These two readings are where my ideas on Existentialism come from, not an extensive catalogue as you see. And I admit to not having read these books cover to cover. I think I may have mentioned a time or two, however, that there is a difference between being a philosopher or trying to be a philosopher and a historian of philosophy - or at least there should be.

I have been struck by a few very powerful ideas between these pages, and I believe that I have honed in one the most important animating principle of the system of Existentialism - at least in the way, more or less, the way Jean-Paul Sartre laid out the system.

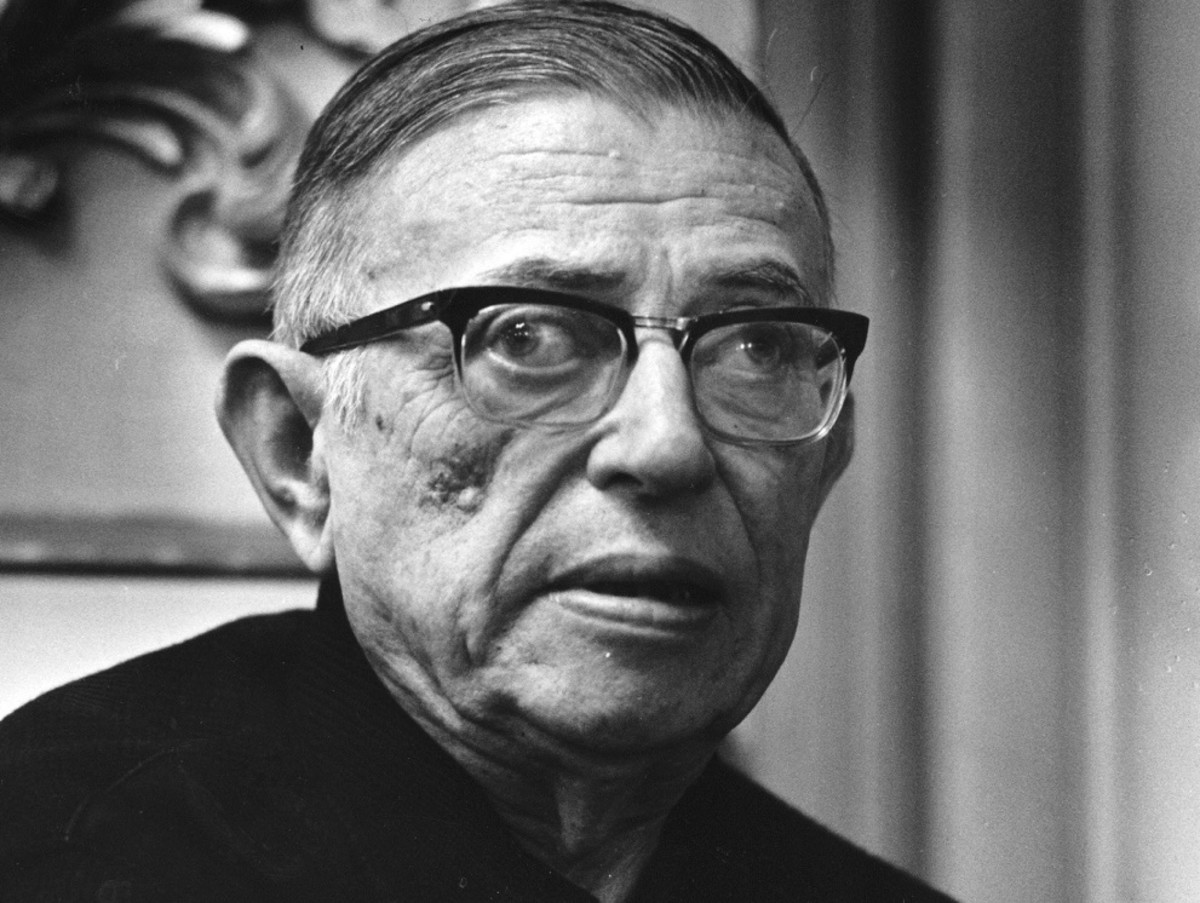

Jean-Paul Sartre, the great French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), an atheist, nevertheless acknowledged that "The best way to conceive of the fundamental project of human reality is to say that man is the being whose project is to be God." "[M]an fundamentally is the desire to be God" (Essays in Existentialism, pp.70-71).

Man is the desire to become God. This is, for me, the primary animating principle of the system. But before we talk about that, we must visit with a prior idea of Sartre's. He said that "Man exists without justification." What does this mean?

The way I've interpreted that is the following: "God" does not provide direct, individual feedback to people about how they're doing with this whole, life thing. "God" does not alight into your bedroom at two in the morning, wake you up and say: "Hey, Joe! Listen, sorry to get you up at this hour. But don't worry about it, I'll give you the strength of a bear for the next two weeks and when you wake up in four hours, you'll feel like you slept for eighteen hours.

"Here, let me get that hangover for you - zzzzzaaapp! There you go. Listen, Joe, I was in the neighborhood so I just thought I'd stop by and tell you how proud I am of you. I like how you're living, man! Sure, you drink a little more than I'd like. But whose perfect besides me, right? Specifically, I wanted to tell you I liked the way you handled that moral problem Tuesday of last week.

"Your solution was an interesting application of commandments three and seven. Good on you, mate! Alright, go back to sleep. I've got a few more stops to make before I get back to the crib. Survivor's coming on in an hour."

No one has an experience like this, whether they be believers, atheists, or anything in between. Because this is so we all exist in a state of anxiety, believers too - no matter how forcefully they assert the contrary, absolute certainty. We live and act in the world and we get feedback, compliments, assurances, criticism from friends, family, our fellow human beings, but somehow its not quite satisfactory.

Its not the same as having external, objective, impartial, and yes, therefore, an extraterrestial source of feedback. Because this is so we have a tendency to try to arrange our lives in such a way that we get as many positive outcomes for ourselves as possible, such that our lives seem to be in accord with some kind of "universal law" that seems to come from outside ourselves.

The idea is that desire reaches beyond itself. "Pascal believed that he could discover in hunting, for example, or tennis, or in a hundred other occupations the need of being diverted. He revealed that in an activity which would be absurd if reduced to itself, there was a meaning that transcended..." and "... Stendhal in spite of his attachment to ideologists, and Proust in spite of his intellectualistic and analytical tendencies, have shown that love and jealousy can not be reduced to the strict desire of possessing a particular woman, but that these emotions aim at laying hold of the world in its entirety through the woman" (Essays in Existentialism, p.69).

I like to be more specific than showing that in a "hundred other occupations," one expesses "the need of being diverted." I like to try, if I can, to identify the specific God-project the activity is aiming for.

Now, "God" represents the eternal, and most importantly for our purposes, the infinite, infinite capacity. God being God, then, there are an infinite number of ways of approaching "him," that infinite capacity. Any activity that seeks to transport you from where you are, the realm of the finite, to where "God" is, the realm of the infinite, deserves to be categorized as prayer.

Traditional, hands folded, eyes closed, kneeling, head bowed prayer is about this. The believer gives thanks or makes an entreaty for aid, she is trying to transport her finite problems to the dimension of infinite resolution.

Bodybuilding is a form of prayer. If we consult Wikipedia we can pick out two very interesting facts about the history of the sport that - given what we have come to understand by now - shows it is not and never has been a mere narcissistic exercise, as some people might think.

The sport seems to have been founded by a Prussian man called Eugene Sandow, referred to as "The Father of Modern Bodybuilding," in the late nineteenth century. What's interesting about him, for our purposes, is that he was a "strong advocate of the Grecian ideal," a mathematical standard that was set up as the "perfect physique" that was meant to come as close as possible "to the proportions of ancient Greek and Roman statues from classical times."

The sport of bodybuilding was founded by a man who tried to create a transhuman or beyond human result in the development of his body. The Grecian ideal was so far away that it might as well be a stand-in for "God" himself.

In the 1950s and 1960s, no one had done more to popularize the sport than Charles Atlas, "whose advertising in comic books and other publications encouraged many young men to undertake weight training to improve their physiques to resemble the comic books muscular superheroes."

The same dynamic is operative here. The comic book superheroes became the Grecian ideal for that generation of American bodybuilders, and this marketing technique of Charles Atlas, in this way, helped to further infuse bodybuilding with a transhumanist goal.

The purpose of bodybuilding, then, is to try to place the bodybuilder as close as possible to the realm of "God's" infinite ability to mold and shape his physique. Bodybuilding tries for the god-like ability to mold oneself with the ease and thorough control of a master sculpture working a piece of clay. Because this is so the bodybuilder is engaged in the act of prayer.