Kieran Behan: Defying the Odds to Rewrite Gymnastics History

Doctors assured him that he would never be able to walk again, but he got to the Olympic Games.

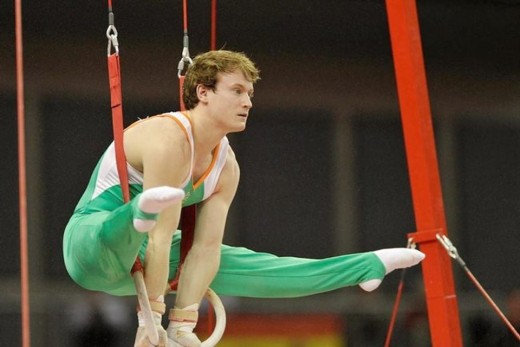

LONDON — Before life threw more challenges at him than one person could bear, Kieran Behan told his mother he would one day be a gymnast and compete in the Olympics.

As a young boy of just 6 years old, he watched the Summer Olympics and fell in love with gymnastics, fascinated by the opportunity to defy the laws of gravity and spin through the air as if he could fly.

However, that was before a series of injuries, two of which were so serious that doctors said he would never walk again: a botched leg operation that resulted in nerve damage, and a brain injury that left him unable to do even the simplest things, like sit or eat.

But Behan, a plucky phoenix standing just 162cm tall, was desperately moving forward towards his rebirth.

“The doctors told me, ‘Forget your crazy dreams, you’ll never walk again, just accept that it’s over for you,’” Behan recalls. “But I kept saying, ‘No, no, no – I’m not going to spend the rest of my life like this. It’s not supposed to end like this.’ And now look at me, I’m an Olympian. They said it couldn’t be done, but I did it.”

Behan, 23, narrowly qualified for the Olympics in January, finishing second to last in the qualifying tournament. He became the first Irish gymnast to qualify through talent rather than a wildcard. He also benefited from a new Olympic rule that reduced the number of gymnasts on each team from six to five, to give more places to athletes whose country does not field a full team.

Many of the top teams, including the United States, criticized the rule change, saying it weakened competition and forced some teams to leave world-class gymnasts at home. But the change had its positives: It allowed athletes like Behan to compete at the top levels.

"Kieran has been through a lot," his mother, Bernie Behan, said through tears. "He deserved it."

Kieran Behan began gymnastics when he was 8 years old and showed a particular talent for acrobatic leaps. But he soon encountered the first of many obstacles along the way: when he was 10, he found a golf ball-sized lump on his left foot.

The lump turned out to be a benign tumor, but during the operation to remove it, doctors pulled the tourniquet so tightly and held it for so long that they damaged a nerve, and Behan began to have poor feeling in his left leg. In fact, the injury was so painful that he would cry out even from the slightest touch on his leg. At one point, he was no longer able to go to school, which caused ridicule from other children who already had a grudge against him.

"They would say, 'Oh, look at the cripple,' and it was really hard for me because I was already doing gymnastics and I was short and I was doing girly sports," he said. "So I would sit by the kitchen window and watch all the kids running around the park and playing football. I was really stressed out. All I wanted was to be a normal kid again."

Doctors warned him that the damaged nerves might never heal. A psychiatrist advised him to prepare for a life in a wheelchair. But they were wrong.

Although it took 15 long months, Behan was a normal kid again. And he returned to gymnastics.

But about eight months after he recovered from his leg injury, another disaster struck. In what he described as a freak accident during training, he hit the back of his head on a metal horizontal bar and collapsed to the floor.

The result was traumatic brain injury and severe damage to the vestibular canal of the inner ear. The injuries affected his balance so much that the slightest movement would cause him to pass out. And according to his mother, Behan would pass out hundreds, perhaps thousands of times while trying to turn his head, eat, and walk without stumbling or staggering like a drunk.

Bernie Behan was frustrated by her son's slow progress during his two months in hospital and took him home when doctors were reluctant to discharge him. She quit her job as an aerobics instructor to care for him.

“He kept telling the doctors, ‘I can walk, tell them I can walk, Mummy,’ and my heart was breaking,” she recalls. “I’d go out into the car park to cry and then come back and say, ‘Yes, Kieran, you can. Together we can. I believe in you, son.’”

Almost two years after the accident, Behan has regained his hand-eye coordination and is back on his feet.

And he returned to gymnastics. To pay for his training, he swept the floors of the gym and jumped over subway turnstiles to get to classes because he couldn't afford the fare. To raise money for him, his parents sold baked goods and candy and washed cars.

Once again, there were problems. He broke his arm. He shattered his wrist. As a teenager, he was hospitalized so often that local officials began to suspect he was being abused.

In 2009, he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee. It took him six months to recover.

But even here he did not give up sports

But in 2010, six weeks before his debut at the senior European Championships, he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his other knee. After everything he had been through, the injury nearly drove him crazy.

"He's come back from all the injuries, but this was the hardest because the championship was coming up and he was ready," said Simon Gale, one of his coaches. "This was too much for him to handle. I wouldn't say he was suicidal, but I was glad his girlfriend was there to look after him at night."

But Behan did what he naturally did best: He pulled himself together again. And he went back to gymnastics. He said he couldn't live without it, and he never doubted he would.

His mother said she often asked herself, "How much more trauma can he take like this?" His mother said she often asked herself, "How much more trauma can he take like this?"

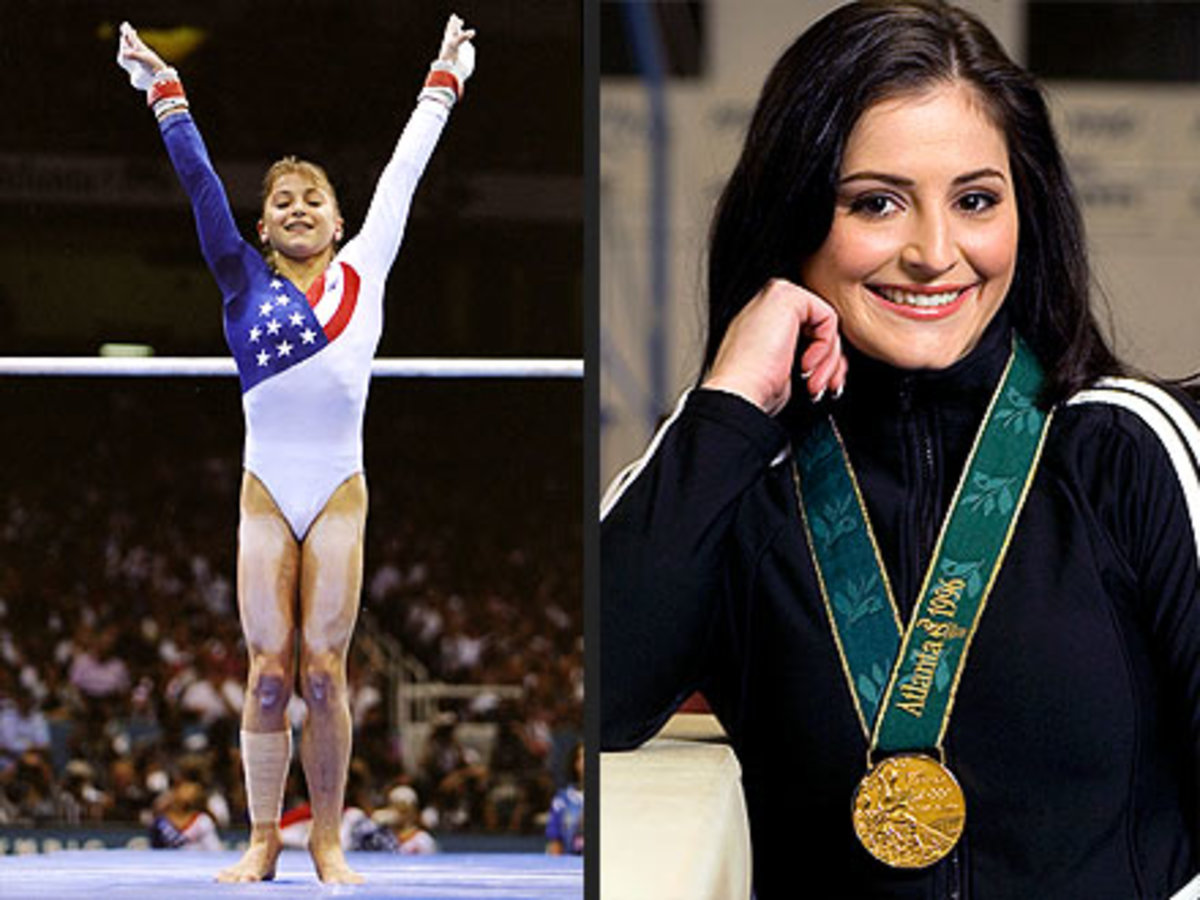

Finally, in 2011, his persistence paid off. He won three medals at the World Championships, including a gold medal in the floor exercise at the first World Championships in Ireland. It was a great start to 2012 – which has been his best year so far.

But just before heading to the Olympics, Behan suffered a slight rotator cuff tear and struggled to complete his final training session, fearing further injury.

At the end he laughed. And then he cried.

"When I got here, I felt like I was in a fairy tale," he said of the London Games. "My only thought was, 'Is this a dream? Tell me this is really happening.'"

Behan competes in vault, horizontal bar and his signature floor routine, but he's not fooling himself into thinking he'll medal or even make the finals. He just hopes his story can help others overcome adversity, whether in sports, at work or at home.

Still, he struggles to explain his resilience. “I guess it’s just in my blood,” he says. “I was just born to do this.”

© 2025 Liam Lucas