9 Frequently Asked Questions About 3D Printing | 5 Similar Technologies

Do you think at some point in the future (say 10 years from now) mostly everyone will own a 3D-Printer just like most own a TV at home?

1. 3D printing sounds really complicated and futuristic, is it really going to become commonplace?

Although the idea of telling a computer to create a physical object sounds like science fiction, it really isn't. 3D printing technology has been around since the 1980s,and lots of big companies have been using it for decades to either produce prototypes or actual products for sale.

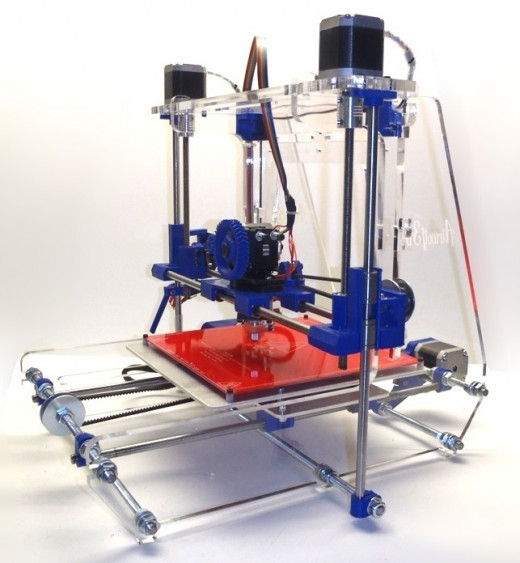

A few years ago, 3D-printing was something only experts could do and only businesses could really afford. Now, though, the technology has become much more accessible, largely thanks to organizations like RepRap and MakerBot. Lots of other companies are making domestic 3D printers now, and they're starting to become easy enough to use and cheap enough to buy that anyone with a bit of patience and willingness to learn can start making 3D-printed objects. And prices are only likely to go down further, so it'll be accessible to even more people as time goes on.

2. Where can I go if I want someone to teach me how to use a 3D printer?

3D printing workshops are starting to pop up all over the country, so check out your local schools and universities to see if anyone's running any classes. If not, you could pay a visit to a dedicated 3D printing service or shop to see printers in action. Many shops run workshops too, where you'll get one-on-one tuition in 3D modelling software and printing.

3. 3D modelling sounds intimidatingly difficult. How can I get started if I'm a beginner?

For starters, you can learn a lot about it in this book! If you're still feeling a bit intimidated, though, a good place to start is online. There are lots of 3D printing services that let you customize objects using simple browser-based interfaces and then order a 3D printed model of your object to be sent to you in the post. That's a pretty gentle way to get started with 3D printing, and anyone can do it. Once you've seen for yourself how amazing it is to get a completely unique model made just for you, you'll want to move onto trying out some free 3D modelling software, and uploading your files to 3D printing services to be printed, and maybe even buying your own printer after that.

4. Aren't 3D printers expensive and hard to use?

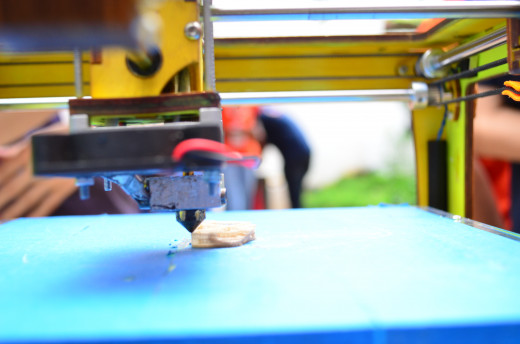

It depends on your definition of expensive. 3Dprinters designed for hobby is to start from around $959. or £700. nowadays, which isn't exactly cheap, but it's not horrifyingly expensive either. The downside of the really cheap printers is that they tend to assume a level of expertise on the part of the user; they often come as kits, for instance, so you'd have to be willing to spend time building your printer before you can make anything. More expensive models are often plugand-play though, and they usually come with dedicated software to ease you through the whole process, from designing an object to finishing your print.

5. What kinds of things can I print?

At the moment, home printers can only really use a couple of different kinds of thermoplastics. They tend not to have huge build envelopes either, so you can only print relatively small things. But that still means you can make things like toys, keyrings, phone cases, and any number of tools and replacement pieces that you'd normally have to buy because they're too difficult to make. Once you know how your printer works, you'll find all sorts of uses for it.

6. Can I print in multi-colours?

That depends on the kind of printer. Most consumer printers only have a single extruder head, which means you can only use one colour or material at a time. Some have dual or triple extruders, which means you can print in two or three colours at once.

Even professional 3Dprinting services can usually only print in one colour at a time, but that depends on the material. Some materials can be mixed with ink and printed in full colour, but those are unusual.

7. Is now the right time to buy?

3D printers are constantly getting more advanced and cheaper. If you buy one, chances are within a year there'll be better, cheaper models on the market. But because 3Dprinting is becoming more popular, and since it's already reasonably affordable, if you do want to get on board early, now is a pretty good time to buy.

8. If I get really good at making 3D-printed models, how can I sell them to other people?

That depends if you want to manufacture them all yourself. If you want to make and sell models, you can do that through the usual kinds of online selling websites, like eBay, Etsy or Folky. If you don't want to print them all at home, though, you can upload your files to a site like Shapeways, where people can pay to have Shapeways print them - and you get a cut of the profits.

9. Will 3D printing really change anything?

It's easy to be skeptical about new technological innovations. Equally, it's easy to get overexcited and declare each new gadget a game-changer that'll forever alter the way we think about the world. 3Dprinting is already pretty embedded in manufacturing. Though, and the idea that the average person will be able to make things for themselves at home is pretty exciting.

5 Similar Technologies

there are a lot of different ways to make things...

Usually, when someone says '3D printing', they mean FDM printing: using melted extruded plastic or other materials to form 3D shapes. They might also be referring to SLS or SLA technologies, which use laser beams to form 3D shapes from powders or liquids. However, there are many other techniques that are similar and which might also be called 3D printing, since they involve using a computer to tell a machine to create a 3D object. Here's a quick rundown of some of the other methods you might come across...

1. Voxel Printing

A voxel is essentially a 3D pixel. The idea behind voxel printing is a bit like building with Lego: models are designed by stacking virtual cubes on top of one another to form a shape, and that shape is then printed out by a machine that stacks physical blocks on top of one another. Unlike FDM printing, which melts down its materials and then extrudes them into shape, voxel printing deposits discrete units into place. It's a slightly different way of thinking about forming 3D objects and one that's fairly easy to understand in principle, since most people will have played with building blocks or similar as children.

Voxels don't have to be cube-shaped, though: they can be spherical, pyramid-shaped or really any shape. As long as all the voxels used in modelling are the same shape, the principle holds. Voxel printing technology is still in its infancy, but it seems promising, especially because it's potentially a far quicker printing method than FDM or SLS printing. Although you might imagine that the process would result in rough, blocky-looking models, that's not necessarily the case, since voxels could be made very small. It's worth keeping an eye on this technology as it develops.

2. Electron Beam Freeform Fabrications

Electron beam free form fabrication (EBF3) is a method created by Nasa, designed to be used in space, it was developed at the Langley Research Centre and shares some similarities with SLS printing. The process involves directing an electron beam onto a metallic surface and then feeding a wire into the molten metal to form the required shapes. The whole process takes place in a vacuum, and the wire solidifies as soon as the electron beam moves on, setting immediately into place.

Obviously this isn't a process that's likely to be translated into domestic 3D printers, unless in the future we all have vacuum chambers in our homes, but for Nasa it could prove pretty useful. There are a few different metal alloys that can be used in this process, and the fact that it works in a vacuum means astronauts can use it to print any replacement tools or parts they might need while on board a space station - without having to wait for things to be sent up from the ground.

3. Selective Laser Melting

Selective laser melting (SLM) is a very similar technology to selective laser sintering (SLS). A laser beam, usually a ytterbium fibre laser, is directed by a computer through a fine metallic

powder, fusing it together one layer at a time in order to produce the desired three dimensional shape.

The process takes place inside a controlled chamber, and a wiper is used to push the powder back into place as the laser moves through it. Several different kinds of metallic powder can be used, including titanium, aluminium and stainless steel.

Although the way SLM works is very similar to the way SLS works - and sometimes, just to confuse matters, the terms are used interchangeably - there is a subtle difference, at least in theory. In the sintering process, the metallic particles don't melt fully: they're only melted enough to join together. In SLM, the powder is completely melted, which can produce a smoother finish and also means that there are more materials that can be used. SLS usually requires a metallic alloy to be used, so that the particles sinter together properly; because SLM melts the powder completely, some pure metals can also be used.

4. Fused Filament Fabrication

Fused filament fabrication (FFF) isn't just another method of 3D printing that sounds similar to the FDM process: it's exactly the same. It involves feeding filament into a 3D printer that melts the plastic and then extrudes it in layers to form a shape specified by CAD software. Why are there two names for the same process? Well, FDM was a trademarked term, so when the RepRap project was set up, it couldn't use it without being sued. Instead, the term FFF was created so 3D printing enthusiasts could use their 3D printers without running into licensing issues. Generally, the 3D printing done on RepRap printers and their successors is just called 'printing', but when another term is needed to differentiate what those printers do from what other kinds of printers do, FFF is sometimes used.

5. CNC Looming

CNC looming, on the other hand, is very different from other 3D-printing methods, but it's a technology that still comes under the same umbrella. Old-fashioned looms could weave fabric by following directions set out by punched cards; to bring the process up to date, CNC looms would work off patterns programmed in by a computer.

CNC stands for 'computer numerical contraband just as 3D printing software tells a 3D-printer in what direction it should move the extruder head and how fast to do it in order to build up a 3D-shape, looming software would tell a CNC loom how to weave a piece of fabric in order to produce the desired pattern to the right size. Using CNC looms, clothing companies of the

future could let customers design their own clothes and get them printed to fit. Domestic looms could let us download patterns from the internet and create new outfits customized to our specifications overnight.