A brief history of system architecture

Physical architecture of a system is defined by the way it functions. Originally computers were ‘mainframes’ – one huge collection of switches and tapes, with a single input point for teletype or punch cards, and a single output device, a printer. These computers were as large as a building. As time went on they became small as a room. People stood in line for their chance to use the computer. You will still find this type of architecture in colleges for engineering students.

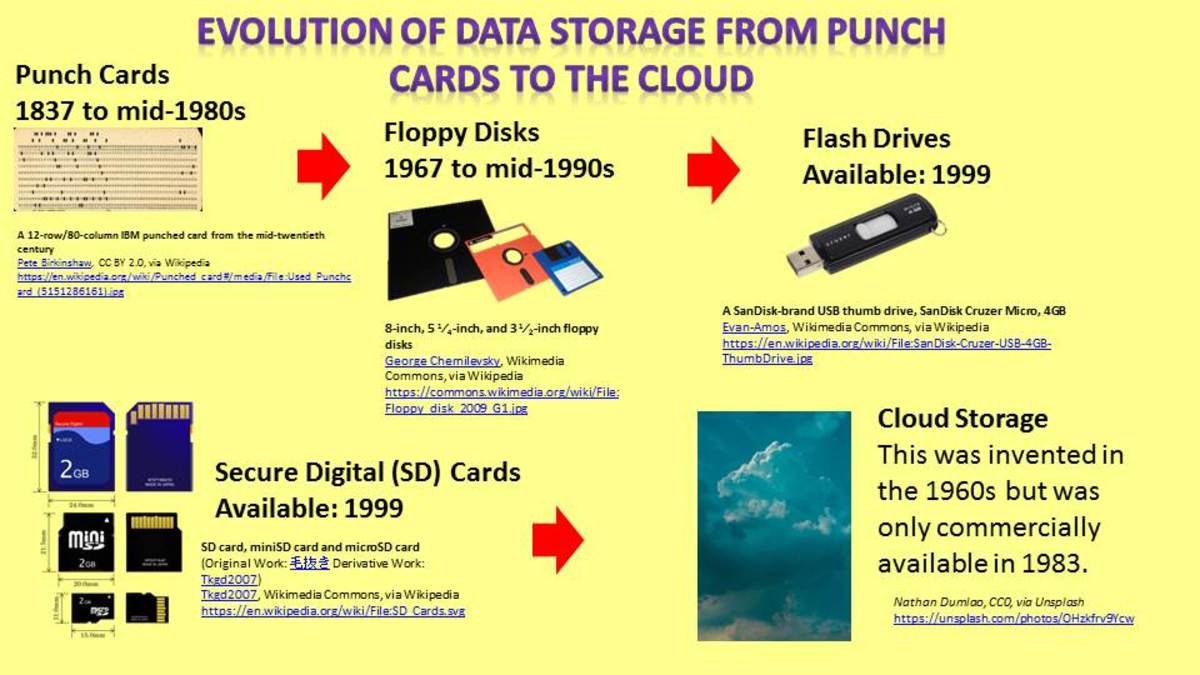

In the 1970s, the personal computer debuted. Since it could not house the large relays of a mainframe, this was seen as a personal super typewriter; graphics were extremely limited in a personal monitor (remember Hercules boards?). Sharing data was achieved by saving things on 5-1/2-inch diskettes. Even the programs that were run on the PCs ran off the diskettes – hard disks were tiny (10 MB) if existent at all. RAM was equally limited. The Motorola CPU chip used in Macintosh, Atari and Commodore PCs opened the possibilities of expanding the usefulness of a PC to things other than word processing.

In an effort to tap the user population that was eyeing the Macs, Intel set about developing the 808x series of chips, which opened up the DOS market to private users. Still, both PCs and mainframes were in the position of a one-machine-one-user architecture.

While businesses needed the power of a mainframe, they could not waste the personnel time having people in line for use (or their jobs waiting in a queue for a mainframe operator). Thus began tiers. Several people needed to be able to access the mainframe at the same time. So “dumb” terminals were placed at most desktops, and e-mail became the fad. A dumb terminal has no processor – it is a monitor and keyboard wired to a main frame. As such, the mainframe did all the work. One may choose to not call a terminal a tier, since it’s more like a lateral expansion. Semantics.

So in the early 1990s people often had two terminals at their desks – a dumb terminal hooked to the mainframe and e-mail, and a PC for their non-shared work. Time on the mainframe could really stretch out – people learned when were the ‘peak’ periods of use and tried to do their work at ‘off’ times. On a Friday at 3 PM, when everyone was trying to wrap up the week’s work, it could take up to an hour just to get a report printed. So anything which could be done on the PC was done there. Because of the familiarity with the mainframe command system, Intel PCs were used more often than Macs, unless the people using a PC were technofreaks and wanted to play with Macs.

As it became apparent that personal computers had a great deal of popularity, and technology soared ahead in RAM, ROM and processors, designers were looking for a way to meld the advantages of mainframes and PCs. That gave birth to the network. In a network, the server does a lot of the work in trafficking that the mainframe once did, but part of the work was shared by the nodes, or “smart terminals”, as the nodes put in queue requests and passed information along to each other. At least, even at $20,000 for a server, it was cheaper than a $6,000,000 mainframe with no trade-in value!

There were a lot of growing pains at this period – many different networking models and operating systems (NOSs). Companies weren’t sure where the future was going, so they bought this and that and experimented. I remember being in one company where I could walk around and find Apples, Macintoshes, Intel (PC, AT, XT), “Trash 80s” (TRS-80), main frame terminals, and at least two different network OSs. It was a hodgepodge. And many companies are still carrying this legacy.

Client/server architecture is usually a network – a server does some of the work and the client (node) the rest. This is not just true of the NOS, but of applications using this architecture – part of the application is on the server, and downloaded to the node RAM when executed, part had to be called directly from the server, and part was local at the node. Yet another part might be in a database on another server. A good example of this was Word Perfect, which kept running even if the network went down – until you wanted to print, which you could only do through the server.

Web architecture could be considered client/server, but the web server is unique in that it must be designed to accept a “universal” language rather than the language of the NOS. Then the web interface usually has to communicate with information on data servers. All of these possibilities required new languages which were more efficient than AIX or VMX, which did not work well with the PC architecture.

IBM came up with a model of the various communication layers used by a NOS – those that ‘spoke’ to the business applications, those that handled the user interface, etc. If I remember right, there are 7 defined layers. Each of these layers actually performs a distinct function independent of the other layers. It is the synchronization of these layers, and the separation of responsibility between the node and the server or multiple servers (e-mail, web, data, applications, users) that make them so powerful.

As prices, technology and applications began developing for the tiered architecture, “migration” and “maintenance” became keywords. For over a decade companies were still seeking the best possible answer and then migrating over to their architecture(s) of choice. Applications were wholly revamped and it was like having a totally new system at each migration. Finally this has slowed down, and maintaining the applications and growing technology is the major activity of the IT departments.

The old method was that one technofreak or another decided “this” was the way to go and a company would simply adapt his/her recommendation. This sometimes resulted in smokestack architectures, piling one obsolete setup on top of another. In those days, there was no such degree major as computers – computer managers were either mathematicians or electrical engineers.

This is no longer an acceptable approach. Now we must look at what is there and develop a sane plan to maintain what we need from the legacy systems, see far enough into the future to be sure any replacements have a future, and design a migration which is not only successful but reasonably priced.

The data is the common point of reference for old and new systems. Since all of these systems process data that come from predominantly the same places, the different environments must seamlessly communicate and often share the same data. Hence, one of the most important considerations in systems architecture is the architecture of the data. And the next step is to migrate this data to a newer architecture.