Archimedes' Rear End Worked Nicely

Many moons ago I worked in product development and systems applications in medical companies.

You might think that I was some sort of electronics and chemical genius to be involved in such stuff. No. These things were super-interesting, but my understanding of them was super-limited. Perhaps "fascinating" might be the better word to describe how they seemed to me. I was the only one in the bunch who did not know which end of a diode was the plus end and why electrons traveled "the wrong way" along their circuit-bound paths or how much salt it took to melt an ice cube. All the same, I did know who to ask about that sort of stuff.

Believe it or not

Believe it or not, those may be the reasons why many of my goofy ideas wound up as marketed and successful products. I would see the need for something, read about what other people had done to fill the need or solve the problem, talk with my talented co-workers about things and, powie, there would come a product or the solution to a problem that needed solving.

Thomas Alva Edison Lighted the Way

One time our development of a "spark gap camera" for the mapping of gamma radiation emissions from medical patients was stymied. Spark production in the camera's detector gas by that kind of nuclear radiation was way too inefficient. I had long ago read about the metal, tungsten, used in ordinary light bulb filaments, being "electron-loose." The gas in the spark gap cameras sparks nicely when struck by beta particles. Beta particles are just electrons that are zipping along at a good clip of speed. So I suggested to our techies that they coat the inside of the spark camera "lens" with a micro-thin layer of tungsten. When the electron-loose tungsten is zapped by energetic gamma rays, useful sparks, and lots of them are produced. Problem solved. Actually, now that I am thinking about it, maybe it would have been better to use tungsten-coated detection wires inside the camera instead of a tungsten-coated entry window. Oh well, that was a long time and a long distance behind me now.

Two for One

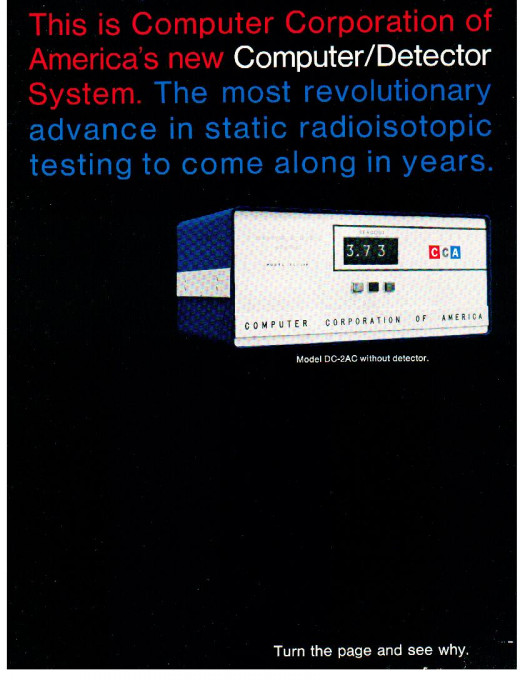

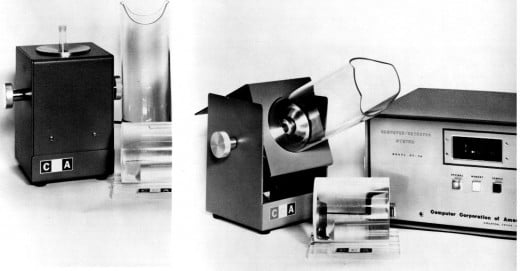

We faced the same sort of thing with a need for two different kinds of radiation detector coupled to the company's computerized radiation counter (scaler). The need was to keep the price down as low as possible while being able to offer customers two totally different kinds of detector - one for counting radiation from test tube samples and another for counting radiation from inside of living patients.

In this instance it was a master mechanic techie who put my "convertible detector" ideas into action. Several hundred of these were sold to medics all over the country.

Time to Push the Button

Maybe the most fun to be had came along with the introduction of the first commercially available electronic wristwatch. That wristwatch was put onto the market by the Hamilton watch company at the amazingly high price of $2,100. A most impractical gadget it was. To read the time from its watch face, the user had to press a little button so as to light the red neon number tubes in the watch's bulky case. The reason for this inconvenience was that the glow tubes sucked the life out of the watch batteries. Battery life without a recharge was only about one hour for time-viewing with the red lights glowing.

I thought of a way to provide continuous charging to the watch batteries. One of our component suppliers helped to produce a working prototype. It was tiny in size so as to fit into the watch case and it worked continuously, keeping the batteries up to charge and allowing continuous time viewing by the watch user. Too bad for us that Hamilton quickly abandoned that product, but, for a time, they were rather "hot to trot" about making a deal with our company bosses to get their hands on our invention.

I was sitting here this morning considering how this long-abandoned technology might be adapted for good use in today's many electronic "smart watches." I understand from reading posts on the Internet that battery life in those watches is quite limited. I can see little reason why continuous battery charging could not be effected for the "smart watches" much the same as we did it for those early Hamitons.

The Archimedes Rear End Patent

Along came the first of my chemical testing patents. Chalk this discovery up to the situation of wanting to tell some testing product peddlers, "Listen, you dummies, not THAT way. Here is how you should do this stuff..."

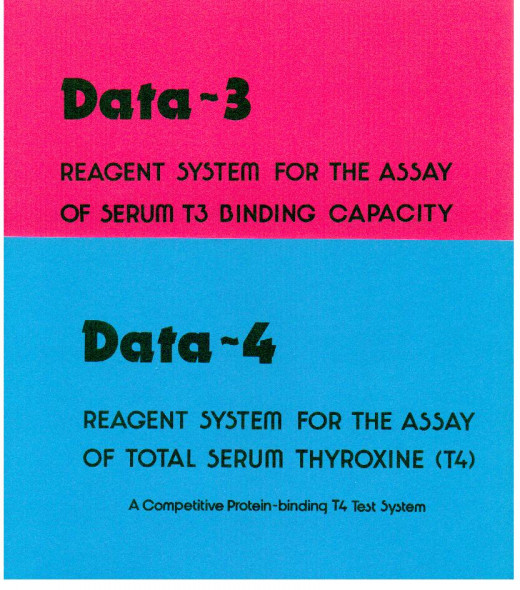

Our laboratory was called upon to perform at least 100 extra tests per day of one laborious type - but there were only two of us who worked there. We had plenty to do already. Our supplier offered test kit materials for the tests to be added to our schedule. The problem with what they offered was that the steps required in their test method and its materials was that there were way too many steps required and that the materials were inconveniently difficult to manipulate. Additionally, their test method required us to obtain new equipment for sample mixing and separations.

The company representatives demonstrated their test kit to me. As I watched them performing the steps required within the testing, I almost immediately thought, "My gracious. There is no way that we are going to be able to do our regular work, plus another 100 of their test kit units every day." In a flash, a better way to do what they were doing popped - much like that cartoon of the popping light bulb over someone's head when they come upon a new idea. I began to tell the company people, "Look here, let me show you how to do this test you want to sell to us..." I actually began to grab some things from the shelves with which to demonstrate a better method to them. As quickly as I had started in my smart-mouth lecturing to the company people, I stopped. They asked me to keep on explaining. I knew better than to do that.

When I got home that evening, I sat down with my pad and pencil and wrote out what I believed to be a patent application. Of course, it was not, but what I wrote helped the real patent attorney folks when it came time to actually apply for a patent.

After doing some bench testing of my new method, I wrote the procedure into an article which was published in a journal.

I enjoy smiling about what I call my invention - "The Archimedes' Butt Patent." It features radioactive isotope-tagged hormones (or others) loosely attached to some ion-exchange resin beads that are stuck between expanded polystyrene beads (as in throw-away drinking cups). These are formed into rounded sticks that fit loosely inside test tubes in which small amounts of liquid samples are contained. The sticks push the liquids into relatively thin layers surrounding the sticks, thus accelerating reaction between whatever the sticks are carrying with them and the targets in the test liquids. This is remindfull of when Archimedes solved the Emperor's fake gold recognition problem by sticking his rear end into a bathtub.

An interesting sidelight to this adventure using expanded polystyrene beads to make testing sticks is that the first sticks were cut from large plastic beer cooler boxes a friendly plastics molding company made for me. They used their polystyrene beads and my big bottle of ion exchange resin beads mixed in before sucking all the beads up into their beer box molder.

That just goes to show you that all molds are not always in dark, damp places, and that some molds are even good for medical testing.

Almost a Sleasium of Magnesium

Not in the way of boasting here about being a great an inventor and all of that, I did the same sort of messing around with chemistry stuff as I did with the electronics and with that Archimedes (so-called) invention. Know little - do much, so to speak. Came along one time with a nifty patent on a system to detect and measure tiny amounts of target molecules in samples of body fluids - blood, urine, and so on. Funny thing was, the whole concept was due to my ignorance and a strong desire to skirt around a medical testing patent held by some folks who had done "wrong" to our company. Those folks had patented the use of granules of magnesium carbonate as adsorbents in test samples. My idea was to avoid using magnesium carbonate, substituting calcium carbonate powder in its place. (Shows you how very little I understood about patents, right?)

The White Cliffs of Dover Are Not Medical Grade

I tried to buy some medical reagent-grade calcium carbonate. No soap. There was no such thing available to me. It was therefore necessary for me to make my own, using approved chemicals in the making. I planned to make a carbonate solution and then add a second solution of calcium chloride to the carbonate solution. Calcium carbonate would then be produced. The calcium carbonate powder would then have to be dried, weighed, and distributed to test tubes into which test samples would be added. That's when the light bulb popped. Why not have the calcium carbonate particles form right in the sample test tubes? One squirt of liquid - and we were done. Our product medical test kits, made under the new patent, were sold all over the United States. Not only was there no patent infringement with the magnesium carbonate patent, the patent application examiner declared to us that our invention was the most unusual of any that she had examined in our testing area.

Whatever DOESN'T Float Your Boat

Maybe the best of the "inventions" was the discovery made during that calcium carbonate deal of a chemical that did useful things in costly medical laboratory testing better when the amount employed per test was reduced more and more. I was looking for a chemical solution that would help keep everything floating around and nicely dissolved in it. I came across one chemical that seemed to do just what was needed, but it was bulky stuff, cloggy stuff, in-the-way kind of stuff. Cutting back on its concentration cleared the goopy and cloggy problems, but the more I cut back on the concentration of this chemical, the less it did what I wanted it to do. As the concentration got lower and lower, I noticed that the particles of test stuff that had been afloat were all sinking to the bottom of the test tubes. Finally, the concentration of the chemical got really low - almost to zip-pop-nothing in fact, and particles in the test tubes shot down to the bottom of the test tubes like steel balls in a glass of water. Not only did the particles zip to the bottom of the tubes, they stayed there even when you dumped out the liquid.

Well, that solved another costly laboratory testing problem - the loss of target solids when test tubes are drained of their liquids. As it came to pass, this became a very successful, very useful, and very profitable medical laboratory product.

Did You Ever Meet a Mother Named "Necessity?"

You would think that I might run out of stuff to come up with, but it didn't stop with those nifty things. There is probably some limit to it all, but there is doubt that the limit is close enough for a date to be circled on the calendar.

As I sit here at my ten-dollar keyboard, I am caused to marvel at the several things I happened upon while knowing so little about any of them beforehand.

Maybe it is true that "Necessity is the mother of invention." What I am saying is that other things might be involved as well, to wit:

Ignorance, curiosity, anger, luck, fear, and amusement.

Yes, invention and discovery should be fun, and fun they truly are. The rest of those things may add to the mix, but it is the fun that makes it work so well and makes me feel good about having played at it.

Now Comes Your Turn

There are things for you to think about the next time you consider the wisdom of tossing a piece of chocolate onto that egg you are frying atop the stove. Will a drop of honey on the cucumber vine bring more pollinating bees on visits? Do water-filled clear plastic bags really keep flies off the patio or should you hang sticky flypaper nearby as well. Just ask the questions. Then wait for the answers to be shown to you, either by actually seeing something working (or not) or seeing it in your thoughts.

It will amaze you what can result from your having some fun.