Nuclear Power Plants and Electricity

Are nuclear power plants safe?

Facts about nuclear energy

Is nuclear energy safe? Is it green and clean? Is it cheaper than other sources of energy? The best answer for some of these questions is “It depends.” And each person has to examine the facts and decide individually about this controversial source of energy production.

Various natural disasters and problems in nuclear plants in recent decades have raised concerns about whether nuclear energy is a smart choice. The 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, which caused serious damage to a nearby nuclear plant, is the most recent high-profile incident in that industry.

Nuclear energy usually gets the black-hat in arguments about the environment and safety, and it is heavily regulated, yet many people believe it is safer, cheaper and ‘greener’ than other sources of energy. The fears of radioactive emissions and even meltdowns, however, make opponents as stringently against that industry as the supporters are in favor of it.

Some countries are heavily invested in nuclear energy and it is a major source of power for millions of people across the world. Those in favor of it say it is Green because it burns clean and doesn’t directly send emissions into the air. Those against it point out the serious problems faced in storing radioactive waste for many generations to come.

Video inside a nuclear power plant & how nuclear energy is generated

How do nuclear plants create electricity?

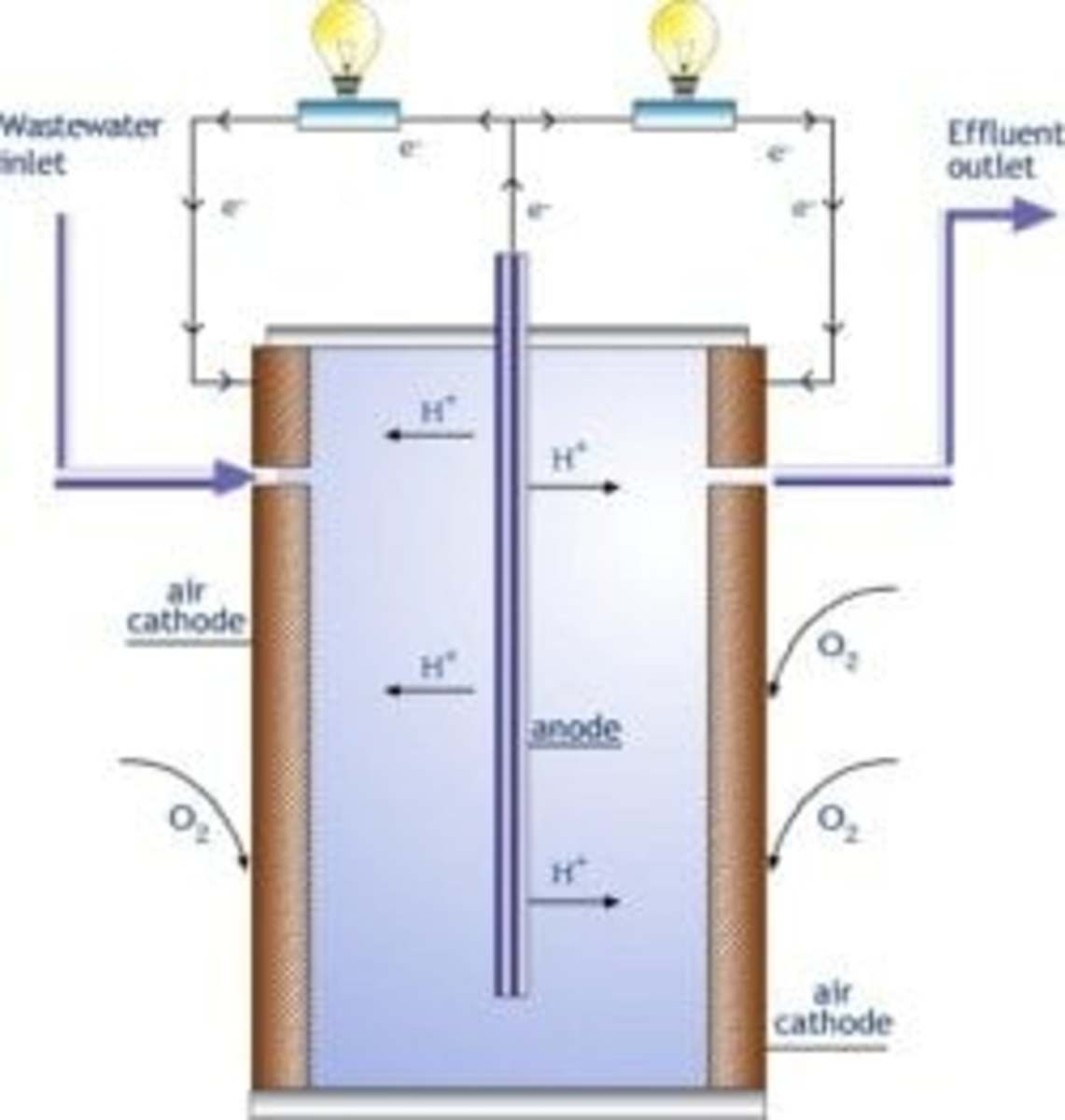

It would take a few engineers and some physics experts to explain the entire process, but the simple explanation is that nuclear power is created by splitting atoms (specifically, uranium atoms). The fission process (meaning, the splitting process) creates energy in the form of heat.

Nuclear plants produce power by harnessing and using the heat (in the form of steam) and using it to drive huge turbines similar to those other types of power plants.

Nuclear reactors also have to be cooled as part of the process (just as we need coolant in our car radiators). The rods in a nuclear power plant have to be submerged at all times to avoid overheating and a possible meltdown (one of the most feared incidents in the industry).

Regardless of the specific technology used at a plant, this is an important element of safety and accident prevention throughout the industry.

In fairness to the plant in Japan, the plant’s systems did what they were supposed to do during the disaster, but the combination of extended power outages (leaving the cooling operations to run on batteries and back-up generators, which can only operate for a limited number of hours), flooding and other by-products of the earthquake and tsunami taxed the plant’s redundancy systems beyond their capabilities.

A nuclear meltdown and disaster

What is a nuclear meltdown?

The nuclear crisis in Japan following the 2011 tsunami raised new questions about nuclear meltdowns and the overall safety of that form of energy.

Criticism of nuclear energy is not new. The movie The China Syndrome, combined with the scare at the Three Mile Island plant and the disaster at Chernobyl decades ago put the term "nuclear meltdown" into our collective lexicon almost overnight. But many people don’t understand what happens during a meltdown.

Quite graphically, a meltdown is almost exactly what it sounds like. If a nuclear reactor overheats beyond its ability to be cooled, the reactor’s assemblies began to, well, melt.

An added risk is that the uranium can melt as well and emit dangerous radioactive material into the environment.

Aside from the huge task of damage control to prevent a bigger disaster, when this happens, the plant itself will need massive repairs, costing many millions (or even billions) of dollars.

In Japan, the issue of repair was complicated further because, in a frantic effort to prevent a worse disaster, corrosive sea water was used as an emergency coolant to try to stop the overheated systems from further (very dangerous) deterioration). This left the reactor unusable and most likely beyond repair.

The Japan incident begs the question of how many stop-gaps and safety systems must be in place in order to adequately anticipate and address potential disasters of any sort. And the cost of fitting a plant to meet every possible situation would be exorbitant.

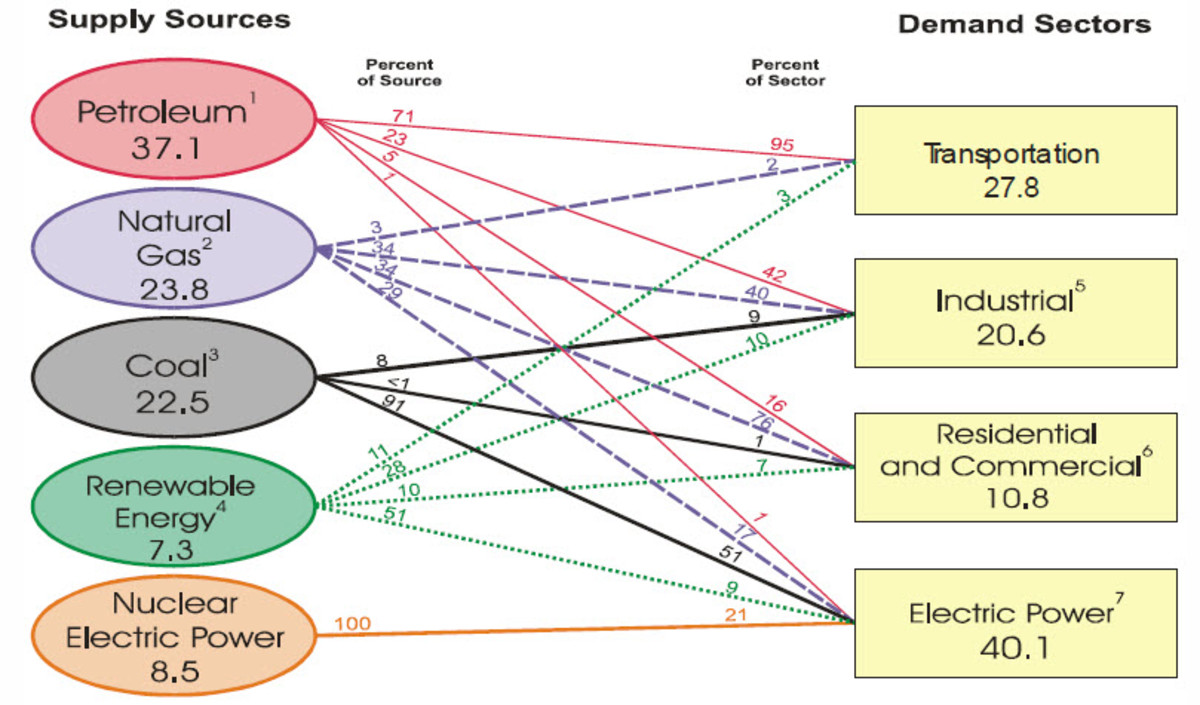

Comparisons of various types of energy power plants

How much electricity comes from nuclear energy plants?

Worldwide, about 435 nuclear plants are in operation in 30 different countries, and they produce about 16 percent of the overall energy consumed in developed parts of the world.

The United States has 104 licensed plants that produce nuclear energy, generating the largest output of that type of energy in the world. These plants provide about 20 percent of the country’s total energy consumption.

France, however, gets 75 percent of its energy through nuclear power sources, with only 58 operating plants and a lower overall output of nuclear energy than the United States. The reason for the contrast is that the United States consumes far more energy than other countries.

Globally, 62 more plants are under construction (China, alone, is building 26 to add to the 16 already in operation in that country).

Book about nuclear power

How safe is nuclear energy?

Nuclear energy proponents point to what they feel is a strong record of safety in the industry. Compared to the 700 or so workers they say died in extracting coal or oil in America, they say not deaths have happened In the United States from nuclear power production.

Proponents also feel nuclear power leaves a smaller carbon footprint, because its waste can often be reprocessed to produce more energy, and whatever is leftover can be, they say, safely stored in deep repositories. The waste from an entire lifetime of use, the industries say, would only be large enough to fill a bottle of designer water.

With a global community that feels increasingly smaller each decade, however, the above claims of safety haven’t comforted those who remember the disasters at Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and the more recent incident in Japan. Nuclear power experts say Japan’s incident was more related to the earthquake and tsunami than to a flaw in the design or operation of the plant.

However, if other natural disasters occur near nuclear plants elsewhere, is there a risk of a plant’s cooling system similarly being crippled due to circumstances that test the plant beyond its design capabilities?

Video on Chernobyl Power Plant

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster and explosion

Along with the 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant in Japan, the 1986 nuclear accident in Chernobyl in the Ukraine is classified as a Level 7 event on the International Nuclear Event Scale. These two events are the only two incidents given that serious of a rating on the scale.

The Chernobyl catastrophe began on a Saturday in April of 1986, during a systems test on one of the site's reactors. A sudden surge in power output caused an attempted emergency shutdown, which then created an even more escalated surge in power.

A series of explosions in the core of the reactor followed, as well as a vessel rupture, which ignited the graphite moderator. The explosions and fire produced a huge amount of highly radioactive-contaminated smoke, which spread into the atmosphere and covered an extensive part of that geographic region, requiring more than 350,000 people to be evacuated. Many left suddenly and did not take personal belongings, but ended up being permanently relocated and still cannot retrieve what was left behind due to continued contamination.

Twelve European countries were affected by the radioactive smoke traveling through the atmosphere. In addition, lakes, rivers and reservoirs in the area were polluted in the immediate days and weeks following the disaster (levels of radioactivity in water sources declined after the initial period, though).

At least a half-million workers were involved in the effort to contain the damage and prevent further harm, at an estimated cost of 18 billion rubles.

There were 237 acute cases of radiation sickness after the accident, and 31 of those victims died within the first three months following the incident. There are varying estimates of the long-term effects on the health of those who lived in the area, ranging from 4,000 anticipated deaths (from various forms of cancer and other health issues) to thousands more.

The economic cost of the disaster has never fully been established. To this day, contaminated buildings sit empty, and the countries affected continue to incur expenses related to damage control, containment, the impact on agriculture, health issues and other direct or indirect effects of the accident. In Belarus alone, the estimated costs exceed $230 billion in U.S. dollars.

The accident is also believed to have escalated the move toward the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Overall, the aftermath and effects of the Chernobyl disaster are still happening and cannot be fully understood or quantified for many decades to come.

What Do You Think About Nuclear Power?

Are you in favor of nuclear energy as a power source?

How old are nuclear plants?

The answer is - older than many of you who are reading this right now.

Many nuclear plants across the world are several decades old. All are made of materials that age and deteriorate over time, which means some plants are now reaching the point where they’re obsolete and beyond the scope of reasonable upkeep and maintenance.

What happens to a dying nuclear plant? Everything in the plant must be disposed of or repurposed (if at all) in a safe manner. Many parts of the plant aren’t exposed to radioactive materials, but the systems that produce energy will need to be screened for radioactive materials and disposed of in a manner that protects not only those who are alive now, but many generations to come after us.

Perhaps some plants can be reengineered and fitted with newer technology and safety features. But some will probably not meet the standards needed to allow them to safety operate beyond their current lifespan. Which leaves nuclear energy companies and the communities depending on them for power with the uncomfortable task of deciding what to do with a giant piece of hazardous waste in the form of an empty plant that can’t be used for much else.

Book about nuclear reactors and nuclear energy

Is nuclear power an affordable source of energy?

While nuclear plants might be cheaper than some sources once they’re up and running (in terms of daily operating expenses), they require enormous amounts of money to design and construct in a manner that meets safety standards. The technology is not cheap, and although nuclear plants can use less land that some other energy sources, the systems and equipment installed on the land can far exceed other types of energy costs.

A properly operating plant, which has been properly engineered, does not pollute the air with emissions or harmful byproducts. However, solar and wind energy are similarly clean sources of power that don’t emit pollutants into the air.

Nuclear energy can indeed produce impressive amounts of energy from relatively small amounts of material (uranium). But that material has to be harvested, protected (even safe-guarded), transported and carefully managed during energy production.

Wind and solar plants harvest their main resource on-site and do not require the safety or security measures nuclear energy demands. But those sources are not as widely used and are still in the developmental stages of efficiency and distribution.

Nuclear proponents feel the small amount of material (usually uranium) needed to produce a sizeable amount of energy is a good trade-off compared to the huge investment in oil or coal that would be required to generate the same amount of power. Nuclear energy is considered a globally available and reliable source of power, too, because the radioactive material needed for production can be found in many parts of the world.

However, the cost of building nuclear plants continues to grow as more regulations and safety measures are (justifiably) imposed on the industry. These costs, as well as the cost of waste containment for spent fuel rods and lower-level waste materials must be taken into consideration when evaluating the overall affordability of this source of power.

Low-level waste can include contaminated items such as tools, portable equipment, clothing and other items that have been exposed and are radioactive.

Those items, along with the more high-profile waste products such as spent fuel rods, and the contaminated byproducts a plant generates have to be safely contained, not just for the next few decades, but for thousands of years.

The logistics alone of storing and then monitoring the waste storage facilities or locations for millenniums are staggering to imagine. And we cannot predict the expenses future generations will incur in trying to track and continue to safely contain waste we generate today.

© 2012 Marcy Goodfleisch