How to Win an Argument on the Internet

The Internet Debate

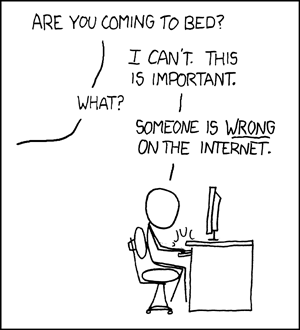

Someone I disagreed with on a forum once told me, "In an internet argument, nobody wins." As anyone who has been on the internet for some time will know, there is someone to disagree with just about anything you say and this is no exception: I must disagree. You can win an internet debate. The trick is to identify the purpose of the debate and pursue that purpose doggedly and impersonally. That's not a very helpful statement on its own. I'll go into it further. First, though, we'll have to identify the various kinds of debates to be found online.

Types of Debates

As we know, internet debates arise when one person makes a statement

and another person disagrees with that statement. So the genesis of a debate is from a

statement. The form that statement takes contributes to a debate its

essence or nature. As one may recall from elementary school, there are

broadly two types of statements: facts and opinions. So there are

broadly at least two types of debates:

1. The Exchange of Opinions

2. The Pursuit of Truth

This should be straight-forward. Either a debate is x or it is not-x, where x is, say, objectivity. There is a complication, however. There may be more than one way to be not-x. So let's add another broad category, a category designed to occupy the region between objectivity and subjectivity,

3. The Discussion of Taste

Naturally there

can even be disagreements about what occupies these categories. For

instance, does morality constitute a debate about opinions, truth, or

taste? I happen to fall in the 'truth' category, but not everyone will.

For the moment, that's not important. We should now look at the purpose

of each type of debate. Once we know our purpose, we can see how to go about and how not to go about achieving it.

What's the Point?

So why engage in any one of these forms of debate? That's the question one must ask and answer: what is the purpose of the debate? If you just feel like arguing for its own sake, annoying others, or blowing off steam, then you're a troll, you don't need this article and you can go away. But we're going to assume you're a reasonable person. However much evidence may accrue to the contrary, most people online are reasonable. They too enter debates for the same reason you do and with the same confusions you do. Reasonable people enter debates of one of the three above kinds and for the following purpose.

1. In an Exchange of Opinions, there is no right or wrong, no truth or falsehood. If the debate is indeed a matter of opinion, no-one is in a position to say another is wrong. So let's take a recent debate. Stephen Hawking recently announced that because extraterrestrials are likely to be dangerous seeking them out is foolish. He bases his opinion on various facts about human exploration. Opinions are, of course, based on facts and reasons one considers sufficient. One can discuss those reasons and the facts; but ultimately the position that extraterrestrials should or should not be sought out is a matter of opinion. You can't prove Hawking right or wrong. In reality, there are merits to both positions. The best one can hope for is to understand Hawking's position fully and make your own position as understood as fully as possible. So the real goal in an Exchange of Opinions is to fully understand one another. The nature of an exchange is to grasp a piece of another's mind. In other words, one seeks clarity. We continue to discuss only to make our opinions clearer to one another and indeed to ourselves.

2. The Pursuit of Truth is a matter of fact. Where a fact can simply be shown on wikipedia there is no

problem and no debate. Either bananas exist or they don't; I eat them and there are pictures of them all over the internet, so they do indeed exist. The debate occurs when there is no way to

readily and monolithically present the fact. For instance, that humans evolved through a process of natural selection is either true or false. Yet, there are those who

disagree about whether humans have or haven't evolved. Although categorized

as a fringe, a number of people believe and believe there

is good reason for their belief that the theory of natural selection is incorrect. But in the absence of incontrovertible proof for the truth of the matter, you can't prove the Creationist wrong. The best one can hope for is to understand his evidence and why he considers that evidence sufficient grounds for holding the belief he does; and to get him to understand why you consider there to be sufficient grounds for believing the theory of natural selection is correct. So the real goal in the Pursuit of Truth is to exchange data and interpretations of the data for the purpose of discovering which conclusion is most likely to be true, or, to put it another way, which conclusion one has most ground to reach on the basis of the data. At least one of you must be wrong.

3. The Discussion of Taste is a bit difficult. There may not be right or wrong taste, but there is good or bad taste. There is certainly no consensus as to whether the basis of taste is a matter of fact. There doesn't have to be. There is overwhelming support for the view that Bach's Brandenburg Concerti are immensely superior to anything Black Sabbath has ever done. To prefer Black Sabbath is a matter of taste, and, as it happens, bad taste. Prefering Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers to The Big Sleep, as I do, is also bad taste. One can never offer proof that one must prefer The Big Sleep to Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers. One can only offer reasons for preferring one to the other and understand what reasons others have. This would most likely involve understanding the aesthetic interests of another, what he takes to be the basis of a good or enjoyable work of art, entertainment, or whatever the case may be, and what he believes the work under consideration offers to those interests. Ultimately I and an interlocutor may well be approaching films from a totally different aesthetic system. If cinematography and depth of characters is the basis of one's aesthetic concerns, The Big Sleep offers more. But if someone likes beautiful girls, witty dialogue, and exciting set pieces, it comes down to a set of opinions about whether Linnea Quigley is hotter than Lauren Bacall, whether Fred Olen Ray's goofy dialogue is funnier than William Faulkner's clever banter, and whether the Virgin Dance of the Double Chainsaws is superior to the Horse-Racing Conversation as a set piece. A discussion of the merits of aesthetic systems collapses the Discussion of Taste into an Exchange of Opinions; a discussion of one film's capacity to fulfill one aesthetic system better than another collapses the Discussion of Taste into a Pursuit of Truth. Overall, what we seek in a Discussion of Taste is to understand why we each prefer one object to another based on our individual engagement with the objects.

How Not to Debate

Now that we've covered the reasonable person's main purposes for online debating, it's time to get to some strategies for how to win or, in this case, how to lose. What we're going to look at here is some annoying 'strategies' we've all seen and probably had others pull on us. They're very annoying and don't aid in understanding one another or coming to the truth of the matter. They're designed to stump you, trip you up, convince you or convince others that you're mistaken.

A. The Trouble with Tribbles

Remember that classic episode of Star Trek, when the Enterprise is infested with these limbless cat-like creatures called "tribbles"? They just keep multiplying and multiplying! Some people's arguments seem to multiply like tribbles. You start off arguing about whether Jean Chretien was good for the Canadian economy and soon you find yourself simultaneously trying to defend the theories of Thorstein Veblen, your belief that it's acceptible to lie to children about Santa Claus, the need for the legalization of prostitution, and why an anecdote doesn't technically constitute a fallacy.

To say the internet is incredible is a spectacularly banal point but a true one. During verbal debates, one has no choice but to focus on the main point at hand. Making side-comments just wastes your speaking time or leads you down a separate pathway for a time. (Plato's Republic is a catalogue of endless digressions, but in an ordered fashion.) Writing allowed one to defend multiple points at a time, but due to the need for this writing to be published and read by many in order to be a public debate or simply shipped-to and read by another in private debate, there was time for consideration and a certain elegance in honing the points. The internet has combined writing and real-time into a hideous abomination. Every little point that interests us we can comment on at once, in a single response, that is quickly read and receives almost immediate reply. We feel a need to respond to every disagreement or question raised about our previous statement, so suddenly the debate about one point has multiplied into a few, into many, into too many. We know how people online work. They let nothing go by unmolested. A misspelling, a casual mention of what you had for breakfast, and your username could all be interrogated and disagreed with by your interlocutor. The debate will become increasingly frustrating and time-consuming as this continues. One simply cannot juggle a thousand debates at once.

The problem is that your interlocutor isn't able to focus on the point. Most likely unintentionally, he's engaging in tactics that seem designed to question your credibility or just exhaust you. If you've brought into the discussion what you had for breakfast, your hairdresser's perspective, and the films of D.W. Griffith, you've presumably done so for a purpose. If he's simply questioned the validity of all hairdressers' opinions and the significance of D.W. Griffith's place in cinematic history, he's either failed to understand why you raised those points or is expressing his opinion on those subjects without regard for the role they play in the overall argument.

The solution is to simply ignore his opinions insofar as they do not directly concern the main point under discussion. Just because he isn't able to focus doesn't mean you can't stay focused and, in the process, gently focus him. Providing an answer to every disagreement is tempting. Don't succumb to that temptation. If he questions D.W. Griffith's place in cinema, just gently remind him why you brought up the point and if he still doesn't get it, let the point go. Some people will naturally become distracted by examples and surface details rather than the point one is making. Since your purpose, you'll recall, is clarity or justification, all you can do is explain with better examples or get him to offer examples of his own. Allowing the arguments to multiply is the surest way to lose.

B. Give and Take

One of the worst strategies in debating, but especially found in online debating, is the concession. Some of us are much more inclined towards getting along than others. The more we argue and the more heated it starts to feel, some of us incline towards making some concessions in the hopes of softening our interlocutor. Sometimes it does work. Often it doesn't. A lot of people don't feel any particular need to soften up or make everyone comfortable. If you make a concession to one of these people, you'll just feel you've been kicked while you're down when they inevitably use your concession against you. I tend to make concessions and I do feel abused when it isn't reciprocated. The obvious solution is to just not make concessions. If you're going to make a concession, only do so because, under serious consideration, you really do think you may be wrong or you may be ignorant of some matter. But just keep in mind: you won't be thanked for admitting your ignorance; quite the opposite. You're better to hide your weaknesses and ponder them on your own, in private, after the debate.

Ideally, you should keep in mind the purpose of the debate. If someone is interested in an Exchange of Opinions, what good is making concessions? It just exposes an unclarity built into your view. If you're trying to make your position as clear as possible, don't build in unclarity. In the Pursuit of Truth, there is more room for concessions, but still not much. If you're really going to defend a position, you're only insulting your interlocutor by not giving it the strongest defense you can. If you're defending a position you don't really believe in, you'll come across as a troll, that is, one of those who engage in debates just to annoy others.

C. The Schoolmistress

In all my years online, I have never once ridiculed another for his or

her grammar or spelling; I have made every effort to understand what is

said. I've found this respect goes a long way. Many feel insecure about

their spelling or grammar, because many have been insulted for it

already. Not everyone online will have the spelling and grammatical abilities I have. Heck, they might not even have the abilities you have! That's a joke. But seriously, to diminish another on the basis of spelling or grammar is far outside the purpose of meaningful debate. It's an ad hominem. If your grammar is so bad someone can't understand you, the odds are your first language isn't English. You can either drop out of the debate then, or ask for patience. Most likely you're writing in a very understandable manner and your interlocutor is simply being pedantic. Usually pedantry is a way of assaulting another when one has taken an argument too personally.

D. Wilful Misconstrual

David Steinberg: "You've misconstrued me."

Ray J. Johnson: "I never touched ya!"

Perhaps the most annoying and frustrating thing that can happen in an argument is when someone misunderstands you. If you're striving to make your views as clear as you can, or striving to have a serious discussion about the grounds for reaching some conclusion, and you feel someone is purposely choosing not to understand the signification of your statement, you really must wonder whether you're in a conservsation with a troll. Sometimes we really do misunderstand one another. Misconstrual can be tedious, but it may be our fault. We can go back and clarify the point, check to see if it's understood, and don't move on until it is. The same technique must be applied in the case of wilful misconstrual. If that doesn't work, there's simply no way for the debate to go on. If he refuses to undertand what you say, you can never achieve the purpose of the discussion.

E. Rhetoric

i. Emotion

Emotion will likely never be entirely excluded from debates. Sometimes knowing how others feel is an important part of understanding their opinions. But often emotional language is a tactic designed to make others hold one's opinion rather than make one's case before them. As such, emotion does not treat interlocutor's seriously as rational, autonomous people: it's manipulation. Making someone hold an opinion is the opposite of appealing to that person's reason through argument. Rhetoric, actually, isn't as much of a problem online as it is in face-to-face situations. In writing it's difficult to put emotional force behind the emotional language. There is also no present audience to immediately react, as a crowd, to the emotional language. Nevertheless, it is a problem. For instance, in a discussion on Obama's health care, referring to it as 'communism' or calling Obama a 'fascist' are emotion-tinged statements that interfere with the clear understanding of one another's points of view.

ii. The Hunting of the Snark

Debating a professional critic can be a harrowing experience. They are often journalists first, entertainers trained to make cavalier statements that trivialize and ridicule their subjects. They have an audience and they know an audience is convinced by wit. Watching one of Bill Maher's wretched television programs is a virtual compendium of the various ways to substitute snarky comments for genuine discussion. These sorts of comments make an audience laugh or cheer, but they don't go any way toward understand another or reaching the truth of the matter. In fact, because they are generally disrespectful, they will put your interlocutor on the defensive and it will be much more difficult to have a free and meaningful discussion. As difficult as it may be to resist a witty retort when it's perfectly set up, it should be resisted.

F. Eristics

Have you ever heard of an eristic argument? It's a form of argument that arose with Sophists in Ancient Greece. Arguably it arose with Zeno's paradoxes. But Zeno had a very good purpose in introducing his paradoxes. As a follower of Parmenides, his paradoxes were designed to show that all change (motion, growth, etc.) is pure illusion. Eristic arguments have as their purpose only confusion.The Sophists' only purpose was stumping others.

The best-known eristic argument occurs in Plato's Meno. While debating Socrates, Meno pulls out a paradoxical argument that questions the very possibility of learning. In English translations, Socrates calls this a "debater's argument." What Socrates means is that it's a stock argument used by the Sophists. The Sophists were rhetoricians first, philosophers second. They were essentially lawyers outside of a courtroom. These stock arguments were paradoxes guaranteed to stump anyone (except Socrates, of course) should one be backed into a corner. When Socrates started showing the flaws in Meno's arguments, Meno delivers his "debater's argument" thinking that by stumping Socrates it will look like he's won the whole debate. Socrates makes short work of Meno's argument. But eristic arguments continue to be used. New Agers and similarly flaky folk have a satchel full of them--such as the claim that psychic powers can't be proven to skeptics because negative skeptical energy hinders them-- that they use whenever a very reasonable skeptic starts to show the flaws in their regular arguments. Eristic arguments are good for getting out of jams, but they run completely contrary to the purpose of any meaningful debate, which is to find the truth or the understand one another.

Krishnamurti could be a difficult man with whom to debate. His upbringing as an Indian guru made him less than logical in his discussions. David Bohm, who wrote a classic book about how to dialogue with others, is a model debater as he seeks clarification from Krishnamurti. This whole dialogue is worth watching.

How to Win

I said in the first paragraph that you can win an internet debate. I really should qualify that statement now. Insofar as you are reasonable and are debating a reasonable person, you can win. You can win in an Exchange of Opinion if you ultimately understand his position and make yourself understood; you can win in a Pursuit of Truth if you support your conclusion, understand the merits of another conclusion, or successfully show the lack of merits in that conclusion; you can win in a Discussion of Taste by supporting your tastes and understanding the tastes of others. These are all win-win situations. No-one has to come away a 'loser.' You can't win, however, if you're debating a troll. That's a lose-lose situation.

Here are some tips on how to make sure you achieve the purpose of your debate.

A. Principle of Charity

The notion of a Principle of Charity comes from Analytic Philosophy, the philosophy of W.V.O. Quine to be specific. Quine was interested in the way we learn to understand the world through our senses and language. He invented the Principle of Charity as a solution to problems of translation. He argued we naturally do, and ought to, assume others are rational human beings. If someone in another culture points at a rabbit and says, "Gavagai," it would be uncharitable to assume he's telling you "Look at the rabbit-shaped UFO". The charitable assumption is that he's telling you "Look at the rabbit," and that his understanding of a rabbit is as good as yours.

This idea of Quine's Principle of Charity has been applied by other philosophers to broader contexts. Instead of merely assuming others are rational, we go a step further and assume they are as rational and reasonable as possible. To apply the Principle of Charity to an everyday debate is simply to grant someone the strongest possible interpretation of his or her views. More often than not people do have in mind the strongest interpretation of what they've expressed. Taking the Principle of Charity thus allows the discussion to move along smoothly without constantly becoming ensnared in needless clarifications.

The Principle of Charity goes a long way toward stopping problems of (D) misconstrual and (A) multiplication. Imagine an argument between X and Y. X says, "...for instance, dragons tend to breath fire, which suggests..." Y could interpret X to be saying he believes that there are really dragons and that Western fantasy writers have accurately captured their behaviour. But that would be uncharitable. That sort of misconstrual would bog the discussion down in unnecessary clarifications. Y could and should interpret X to be using the example of fictional dragons for a greater point.

B. Don't Try to Win

This sounds paradoxical only because I'm equivocating. I'm using 'to win' in the sense of achieving one's purpose where generally 'to win' in a debate is taken to mean making a stronger case than your opponent. Of course, the latter interpretation of 'to win' is only a victory if one's purpose really is to make a stronger argument than one's opponent. I've avoided the use of the word 'opponent' for that reason. You're never going to convince anyone online that you're right and he's wrong. People don't change their views at the drop of a hat in that way. As infuriating as it may be when you really feel you're right, all you can do as make your point of view as clear as possible and after thinking about it your interlocutor, in his own time, may change his view. I've never changed my views mid-argument, but as a thoughtful and reasonable person, I have indeed changed my views over time. Others do as well. In the meantime, we can make our positions ones they can respect, even if they don't agree with them.

You'll sometimes come across some people who say, "Maybe you can convince me if..." I've never found it satisfying to convince others. I respect their views and don't like the idea that I've been browbeating them out of those views. I dislike the idea that they're making concessions just to get rid of me even more. It flat out offends me to think they didn't even seriously hold the views they had been defending. Trying to beat others, show them they're wrong, show them you're right, is only going to get you and your interlocutor heated, and obscure both understand and the truth. The more you try to win, the more (B) concessions, (D) misconstruals, (E) snarky comments, and (F) eristics will come up.

If you stick to your purpose of understanding, clarifying, and justifying your positions, you will succeed far better than if you try to dismantle the positions of your interlocutors. In fact, seeking clarification will often lead them into dismantling their own positions. Read any of Plato's early dialogues (especially the Euthyphro) to see how Socrates, by simply asking questions, leads his interlocutors into contradictions. Socrates wasn't trying to dismantle their views. He was interested in understand them fully, seeing of these views could be correct. Socrates was always engaged in a Pursuit of Truth.

C. Don't Take it Personally

Part of the problem with arguing online is that every disagreement makes us want to defend ourselves, every bit of information offered makes us annoyed that someone assumes we're ignorant. Letting anything slide is difficult. So you end up with (A) multiplication. The more frustrated you get with the multiplication of arguments, the more inclined you are to make (B) concessions. The more concessions you unsuccessfully make, the more stubbornly you defend your central position without concern for understanding your interlocutor's points or what's true. We all have to learn that when someone disagrees with us online, they're not attacking us; they're just disagreeing. If we don't allow that disagreement to offend us, we can stay focused on the point and make a clear case for our position and strive to understand the point of our opponent. When it's clear you're interested in understanding, even an originally rude interlocutor will usually soften his disagreement. People, I must repeat, are generally reasonable--even online.

D. Be Kind

When most people express their opinions online, it's because they want to talk to someone about these issues and don't get to do it much in real life; it's because they want to be taken seriously; it's because they think their views are important. In fact, there's really no reason to think what any person thinks is in and of itself important; what's important is what any reasonable person should think and that is to that point that most people believe they're contributing. You're the same way. It's only trolls who have no interest in making a contribution. Treating the points these people make with respect shows them that you think their views are important as well, that they're making a contribution. This will aid considerably in keeping the conversation reasonable. Being kind is the surest way to keep out (C) pedantry and (E) snarky comments.

E. Avoid Excess

Don't say more than you need to say to make your point. One doesn't want to be robotic, but try to be as concise and logical as possible. The more you say and reveal, the more room there is to go off on fruitless tangents and (A) multiply points of discussion.

Concluding Remarks

Ultimately, debating online isn't much different from debating in real life. The success of the experience depends upon everyone remaining reasonable and assuming one another is also behaving reasonably. The infinite variety of situations cannot be covered in this article; but what I have covered should set you on good grounds to face the combative world of internet communications.

It helps to remember what small, small beings we are in the grand scheme of Nature. We're all lonely atoms swirling in this inexplicable soup of time and space. Communication is our only way to touch one another, to grab hold and share ourselves before spiraling down into the vortex. The internet puts us closer together than ever. We have the opportunity at every moment to give one another solace in this confusing universe and to listen. Communicate wisely.