Richard Feynman - The Man Who Explained the Challenger Disaster

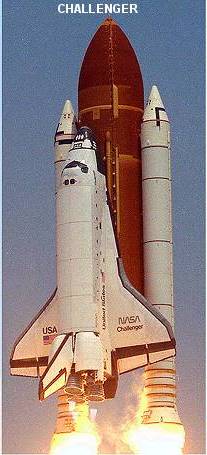

The Last Flight of the Challenger

Space Shuttle Challanger - A Morning that Went Terribly Wrong

On January 28, 1986 at 11:39 EST, the world was stunned by the TV images of the space shuttle Challenger blown to bits in the sky before our eyes. The explosion happened only 73 seconds into the flight. All seven crew members perished.

We had grown so accustomed to technological marvels that we expected nothing less than routine success. There had been 24 successful space shuttle flights prior to the loss of the Challenger. A study concluded that about 85 percent of Americans had heard about the disaster within an hour. One reason for the intense interest in what had become a routine mission was the presence on board of a schoolteacher, Christa McAuliffe. She was the first member of a project called the Teacher in Space.

It would be 32 months before another shuttle launch. President Reagan appointed the Rogers Commission to investigate the disaster. Named after its chairman, former Secretary of State William P. Rogers, the 14 member commission LINK included former astronauts Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride, and Chuck Yeager, the first man to break the sound barrier. The most significant member of the Rogers Commission was the famous theoretical physicist Dr. Richard Feynman.

Feynman's ID badge while at the Manhattan Project

Richard Feynman

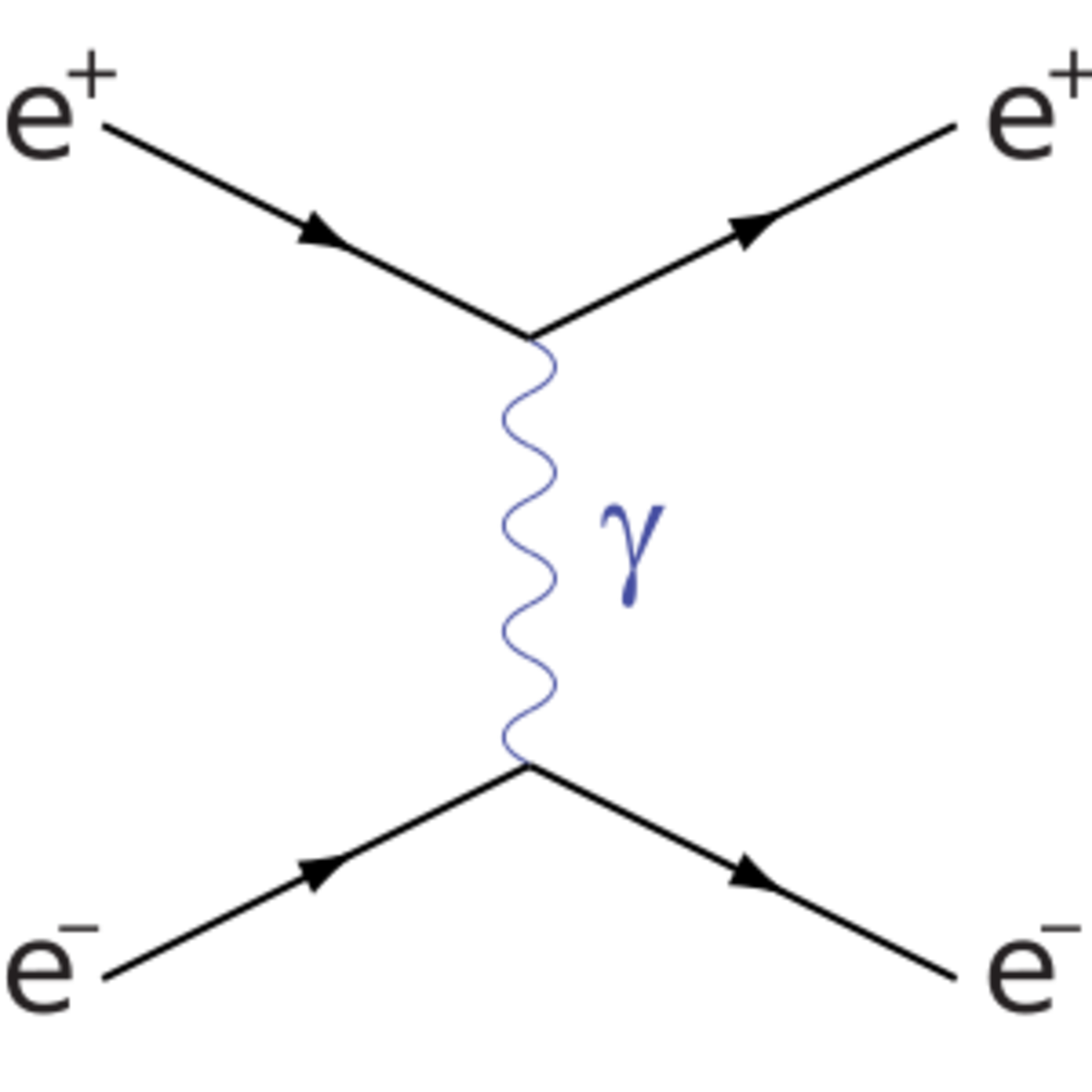

Richard Feynman was born in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York. He never lost his New York accent. After graduating from Massachusetts Institute of Technology he received his Ph.D from Princeton. The British journal Physics World did a study in 1999. In a poll of 130 leading physicists around the world, Feynman was ranked among the top ten greatest physicists in history. Feynman was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1965. One of the things Feynman was famous for was his ability to make difficult concepts easy to understand, such as using drawings to explain the actions of sub atomic particles. These drawings became known as Feynman Diagrams. His independent way of doing things brought him at odds with Commission Chairman Rogers, who wanted the members to follow a schedule agreed to by the commission members. Rogers once said "Feynman is becoming a real pain."

Feynman interviewed engineers from NASA as well as well as engineers at Morton Thiokol, the manufacturer of the O rings, the objects that would eventually be blamed for the Challenger disaster. He challenged the commission's finding that NASA was capable of handling future safety concerns. In his dissenting minority report he concluded that there were fundamental misunderstandings at NASA about the statistics used to determine safety. The NASA numbers held that the odds of an accident were one in one hundred thousand. Feynman determined that the odds were more like one in one hundred. If the commission did not agree to include Feynman's minority report he insisted that his name be removed from the commission.

The O rings on the Challenger were rubber rings that formed a seal between the sections of the solid rocket booster. On the fated flight, one of the O rings failed allowing hot gas to escape and ignite.

Feynman Makes the Complex Simple

Just as Feynman helped make theoretical physics more understandable with his Feynman Diagrams, in his testimony at the televised commission hearing he made it easy for the world to understand what happened on that terrible morning. As you can see in the video to the left, Feynman, with his charming New York accent, took an O ring and plunged it into ice water. When he withdrew it, he demonstrated how the rubber ring did not return to its shape before immersion. thus explaining how the O ring failure caused the disaster. The night before the launch, the temperature at the Kennedy Space Center plunged to 18° Fahrenheit, well below what Morton Thiokol had determined was the minimal safety temperature of 40° Fahrenheit. Feynman could have blathered on and on with numbers and charts and scientific jargon. Instead he used a simple physical demonstration that anyone watching could readily understand.

Feynman realized that his job was not to show everybody how smart he was. His job was to help everybody to understand the reason for a tragedy.