Why The Turing Test Doesn't Stack Up In Terms of Determining Intelligence

Before one begins to make a stance or form an argument on an issue, it is often wise to eliminate ambiguity by pinpointing precisely what the topic in question means conceptually. Otherwise, one may waste time constructing the wrong argument if one does not understand what the issue is to a respectable depth. The answer to the question of whether or not a machine can think very much depends on how one defines what a machine precisely is and what it truly means to think. Merriam-Webster [1] defines the word machine (in the proper context) as a mechanically, electrically, or electronically operated device for performing a task. The nature of thought, however, is a concept quite difficult to have an objective and generalized definition of. Famous mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing was aware of this difficulty and being aware of such is what led him to devise what we call the Turing Test. The test has received much criticism over the years, but does the Turing Test truly make meaningful conclusions about the nature of intelligence?

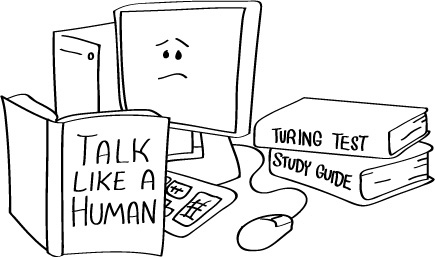

Turing devised the test in hopes to replace the difficult philosophical question of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent activity with a repeatable and observable experiment [2]. The test involves a human judge that engages in normal conversation with a human subject and a machine. All three participants are physically separated from each other and are limited to a text-only medium of discussion to secure anonymity. If the judge cannot distinguish which is human and which is machine, the machine has passed the test. This implies that, according to the test, the machine can be regarded as intelligent and therefore capable of thought. The test is failed, however, when the human judge can distinguish which is the machine and which is the human. This implies (still according to the test), however, that the machine is not intelligent and therefore cannot be regarded as capable of thought.

The Turing Test cannot be regarded as an experiment capable of answering the question of whether or not machines can think for multiple reasons. Turings initial premise to the test implies that the existence of an intelligent entity necessitates the capability of thought. This is seen from his proposal to replace the philosophical question of can machines think? with a test that makes a conclusion about intelligence rather than thought. Since we have difficulty forming a coherent definition to what precisely it means to think, we cannot assume the a-priori relationship of intelligence necessitating thought to be true. This does not mean that the relationship is necessarily false; it just tells us that we are uncertain of whether or not it is true or false. Until we can be certain of this relationship, the assumption remains untrue. From this we can conclude that the argument represented by the Turing Test is unsound in the regard of having an untrue initial premise. How can we accept the conclusion of a test that equates to an unsound argument?

Another problem with the Turing Test is that the essential features of what makes an entity ”intelligent” and therefore capable of thought are disregarded entirely. By ”essential features” [3] I mean only the attributes of an object that have a necessary connection to its essence. As first described by Aristotle [4], this is opposed to accidental features, which have no necessary relation to the essence of the object or entity in question. For example, if one loses an arm, one can still live and be regarded as the same individual. An arm, therefore, is an accidental feature and is not essential to the persistence of an individual. The destruction of intelligence, however, would result in a degradation of the very essence of the individual because intelligence is a part of the essence of a person. The Turing Test operates and evaluates with data that regards the accidental features of intelligence and thought solely. The machine in question obviously must not only be capable of communicating with the human judge, it must be able to do so like a typical human being. Having the ability to communicate like a ”typical human being” is clearly an accidental feature to intelligence. Moreover, having the ability to communicate is also an accidental feature. This is obvious from the countless number of humans that cannot communicate more than a few concepts to each other due to cultural, physical, and linguistic barriers of our world. From this, we can infer that beings that may be regarded as intelligent but are not human would most likely perform worse on the test than human counterparts. Scientists and philosophers have made a good argument backed with empirical data that species of dolphin are intelligent enough to be considered ”non-human persons.” [5] This degree of intelligence should at least be detectable by any legitimate test of intelligence, yet it is obvious given the way the test works that any species of dolphin would not be able to receive a passing score due to communication barriers. Granting some hypothetical technology that ”translates” the language of a dolphin into a human problems still remain. Barring the behavioral and cultural problems of the test, how might we come to conclusions about the nature of intelligence from a test that regards intelligence anthropomorphically? Not only does the actual test depend on an anthropomorphic concept of intelligence, it also depends on the beliefs, culture, desires, and the thought process of the judge for results.

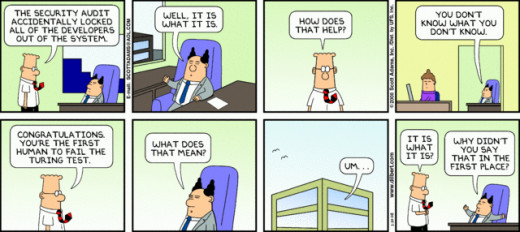

ELIZA, a software representation of a psychotherapist, was constructed by Joseph Weizenbaum in 1966 [6]. ELIZA was able to trick a large majority of judges into passing ELIZA as a human. Yet we know that ELIZA is a simple pattern matcher; it merely stores a bank of typical responses based on the input of the human user. ELIZA does not reason, it merely depends on the user’s input and the developer’s ability to encode typical things to say in a conversation. ELIZA merely stores bits of conversation, it cannot think and cannot be regarded as intelligent. Witt this being said, ELIZA can still pass the Turing Test a significant percentage of the time. This reaffirms my above assertion that the Turing Test only evaluates the accidental features of intelligence, not the essential ones. As John Searle once argued [7], external behavior cannot be used to determine if a machine is ”actually” thinking or merely ”simulating thinking.” In this context, ”external behavior” can be equated to what I refer to as an accidental feature. ELIZA makes it very clear that it is a mistake to regard external behavior as an essential marker of intelligence. Personal bias from the judge is yet another inescapable flaw in the Turing Test. The test operates in the manner that assumes that our human judge is a flawless determiner or attributes which constitute the very essence of intelligence. The test leaves open to the judge to determine what a sign of intelligence is and what a sign of intelligence is not. We know from human nature that often the most human thing to do are things that might be regarded as unintelligent. This simply degrades the criteria of intelligence signs the judge would be searching for considering he or she is attempting to determine which entity is a human being. The intelligence and skill of asking being a ”good detective” also varies greatly per each judge. This may also greatly skew results based on which judges are selected for the test, as judges that ask less difficult questions have a greater chance of being deceived than those who ask more difficult questions. It has been suggested by some that each judge during the experiment ask questions from a bank of questions created before the experiment, but it seems as if that would destroy the natural nature of the conversation that the test aims for. It seems as if the personal bias of the judge in the test cannot be easily avoided, and skews the results to a significant factor. This subjectivity creates a huge problem for the merit of the test, as the answer to whether or not a particular machine is intelligent is capable of changing depending on who the human judge is. Like a typical experiment in the natural sciences, if repeatable results per each properly executed experiment cannot be obtained, a truthful answer to the question cannot be found.

If we are ever to create a test that detects intelligence, we must eliminate as much anthropomorphic bias from the methodology of the test as possible. We must also coherently define what it truly means to think and what intelligence truly means. Only then may the results of the test have any real bearing on the nature of the intellect or lack thereof of human intelligence, artificial intelligence, or any other type of intelligence. Having a coherent, unbiased, and generalized definition of intelligence is particularly important given that artificial intelligence may continue to be fundamentally different than human intelligence, even if it manages to mimic the essence of a typical person to a great degree. While creating such definitions and hashing out such concepts may prove to be remarkably difficult, they are necessary to have a truly meaningful test due to the complexity of the topic in question. The Turing Test was created in an attempt to answer basic questions about the nature of intelligence, but it seems as if its biggest problem is that is was created haphazardly and with disregard to why defining thought and intelligence is so conceptually difficult.

It is for these reasons that the Turing Test holds no bearing on any philosophical conclusions regarding the nature of human intelligence or the nature and future of artificial intelligence. The test has been monumental for the history of AI and continues to provoke thought in those just beginning to study the fields, but research spent on attempting to construct is merely an indulgence rather than a legitimate experiment. Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig were once quoted [8] saying ”AI researchers have devoted little attention to passing the Turing test.” The Turing Test seems to be a test that checks if a machine can imitate humans to a respectable degree rather than a test that determines intelligence. In reality, the test might be rather useful to make conclusions along those lines rather than the nature of intelligence, assuming cultural and linguistic barriers can be overcome. As for using the Turing Test as a legitimate test to make conclusions about the nature of intelligence, we are left with a different story. We cannot truthfully use it to come to any conclusions about the nature of human or machine intelligence due to the philosophical problems of the test.

References

[1] Merriam-Webster. Definition of ”machine” Web. Definition 1f http://www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/machine.

[2] Turing, Alan (October 1950), ”Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, Mind LIX (236): 433460, doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433, ISSN 0026-4423, retrieved 2008-08-18

[3] Guthrie, William Keith Chambers (1990). A History of Greek Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 148. ISBN 9780521387606.

[4] Thomas (2003). Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics. Richard J. Blackwell, Richard J. Spath, W. Edmund Thirlkel. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 29. ISBN 9781843715450.

[5] BBC. Web. February 2012 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-17116882

[6] Weizenbaum, Joseph (1976), Computer power and human reason: from judgment to calculation, W. H. Freeman and Company, ISBN 0-7167-0463-3, p. 188

[7] Searle, John (1980), ”Minds, Brains and Programs”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3 (3): 417457, doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756.

[8] Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003), Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13- 790395-2