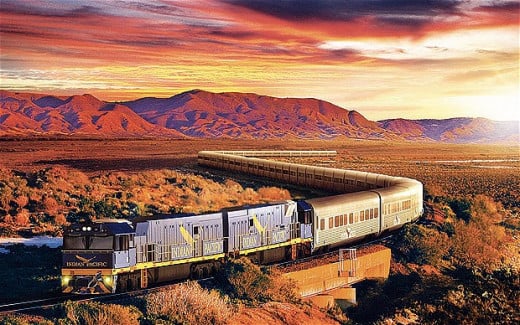

Australia’s Indian Pacific Train - Cruising Green Continent

The Indian Pacific is one of the longest national railways in the world. It takes three days and covers 4,352 kilometres at an average speed of just 85 to 90 kilometres per hour. Passengers see a variety of landscapes and places across the Australian continent. The trip is also a great introduction to local history, as many the places along the track helped to shape modern Australia. Plus, there is fine wining and dining in an excellent restaurant on wheels while admiring the scenery.

The forbidden character of the natural environment that had to be ‘conquered’ by the engineers created serious problems: the steep Blue Mountains, the sheer distance from one coast to the other, and explores perishing from malnutrition and thirst.

But the most formidable hurdle was the Nullarbor area. There is no timber, no food and no water for hundreds of kilometres, due to a 300-meter thick slab of impenetrable limestone (the sediment of a shallow sea that covered this part of Australia for millions of years) preventing tree-roots from reaching the underground water reservoirs.

After leaving Sydney, the Blue Mountains are the first and also the highest landmark. Their steep incline caused the railway builders to lay a tricky zigzag track. Now, tunnels have made the journey easier. The train slides past towns and villages amidst forests and rock formations. The countryside is home to a wide variety of indigenous wildlife like brush tailed wallaby, koala and kookaburra.

Bathurst was founded during the first Australian ‘gold rush’. Mining has created much of modern Australia and a lot of the places along the railway bear witness to Australia’s mining history. Since the mines have disappeared, Bathurst has turned to wine making, small scale, high quality agriculture and dairy production.

The lakes of Menindee mark the beginning of an arid zone. Menindee used to be a river port until most transport by boat vanished. Today the lakes are part of a water conservation scheme, set up to cope with the recurrent periods of drought.

The soil under most western stretches of the Great Dividing Range contains large quantities of zinc, lead and silver. These valuable depots were first spotted by a “bushman” named Charles Rasp. A bounty that led to Australia’s largest mineral bonanza that created the city of Broken Hill, originally a collection of tin shacks, built at random and only meant for temporary usage.

At Crystal Brook, the train veers southwards to Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. The Indian Pacific stays here long enough to allow the passengers a brief excursion into town. Colonel William Light designed Adelaide’s street plan. He envisaged a city centre surrounded by parklands, which still exist today.

The nearby Adelaide Hills and the Barossa Valley are green, lush areas, full of vineyards where some of Australia’s best wines are being produced in world famous wineries, such as Petaluma, Yalumba or Peter Lehman.

About 150 kilometres to the northeast, the formidable Flinders Rangers rise from the coastal palin, dominating the horizon. They are the outer frontier of harsher semi-desert landscape. Australians call this “the Outback”.

Post Augusta in one of a whole string of harbours built along the Spencer Gulf, all constructed with a view to exporting the wheat that was expected to be yielded by the envisaged “wheat belt” stretching from York Peninsula on the coast to Tarcoola and Barton, far inland.

But the dreams of the wheat farmers here were often dashed by a lack of rain and an abundance of salt in the soil, and many of the ports dwindled into sleepy villages around a deserted jetty.

The saline surface was deposited when a shallow sea covered Australia for millions of years—the period of creation that the Aboriginals call “the Dreamtime”. Only “specialized” indigenous plants—like the “saltbush”—can cope with such conditions. It gets water from morning dew rather than from the salty soil.

Where the saltbush ends, the desert begins. At Ooldea, you will find the last natural water source for hundreds of kilometers around. The earth is red as rust, as the soil contains high concentrations of iron. Tufts of plumed spinifex grow among the ‘scrub”’ a low forest of countless midget trees. Underground their roots are very long, in order to reach water.

The landscape seems monotonous, but after a while the desert proves to be a feast for the eye, as described by Tim Bowden (an appreciated Australian TV presenter and author): “In the desert there is always something to see, hawks hovering over unseen prey, wild flowers, changing patterns of vegetation, distant hills, a play of sunlight and cloud in the sky and on the ground.”

For 40,000 years, Aboriginals carved out an existence in this barren landscape, living from what the land offered; only a handful of white people have been able to copy their unique skills.

The hamlet of Cook lost most of its population following the introduction of diesel-electric locomotives; since it was no longer necessary t refill the water tanks of the steam engines. This deserted place once boasted more than 300 citizens, a school, a church, a pub, a swimming pool and even a jail: two rudimentary tin sheds.

After leaving Cook, the train enters the vast emptiness of the Nullarbor plains, although scientists of different ilk—geologist, zoologist, ornithologist, etc—each have their own definition of the “real” border. However, one thing is clear: trees vanish suddenly from the landscape, from one minute to the other. This land is flat as a pancake, featuring nothing but some relatives of the marine flora that used to grow here.

The rare erect objects are mainly man-made: a simple wooden cross for a deceased railway worker, solar panels to support local communication, or a sign that says: “Prisoners of War Encampment”. Around 18,000 Italian soldiers were interned here who had surrendered to Australian troops on Ethiopia during World War II; placed in an environment where not even a fence was needed to keep them here they were. A runway from this campsite would have met with certain death.

They were put to work on the railway line, released after the war and returned to Italy. Quite a few came back at once with their families, in search of a bigger future in Australia—although none returned to the Nullarbor.

You may spot a “Big Red” Kangaroo, venturing out in daylight, a wedge-tailed Eagle, a flock of long legged Emus or even a bunch of wild camels, the great-grandchildren of the camels abandoned a century ago by railroad workers.

A glass of fine mocktail turns the philosophical staring into the featureless plains into a sensation of being in a time machine that carries you back to the days when brave explorers found their way through this for forbidden world.

We are approaching the end of the longest straight railway track in the world, which has lasted for 478 kilometres on end without a single bend. Notwithstanding the attractions of the vast emptiness of the Nullarbor, it’s a rewarding experience when trees reappear, some 200 kilometres before the train will reach Kalgoorlie.

During the months of September to November, semi-desert flowers bloom abundantly during the Australian spring. You will not only see an array of bright and colorful flowers, but also fresh green grass and trees full of leaves.

When the evening falls, the train arrives in Kalgoorlie, where giant open goldmines mark an example of large-scale human interference in the natural habitat that existed untouched for so long. The Indian Pacific stays for 3 hours in Kalgoorlie, allowing the passengers time to venture into town. It’s a small, rich place with wide avenues and romantic two-storey buildings resembling the “cowboy” architecture of mid-west America.

The next morning, the Indian Pacific reaches the undulating plains bordering the foothills of the Avon Valley. Large homesteads and farms dot the vista. Flocks of sheep and cows occupy fenced plots, while other fields are designated to wheat.

The moist, green hills rising up from the banks of the Swan River could not be more different from the dry heart of Australia that the train has just crossed. The Indian Pacific is rolling towards its final destination, the coastal city of Perth, the capital of West Australia, closer to Singapore than to Sydney.