- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting Europe»

- United Kingdom

CJ Stone's Britain: Iron in the Soul (Ironville)

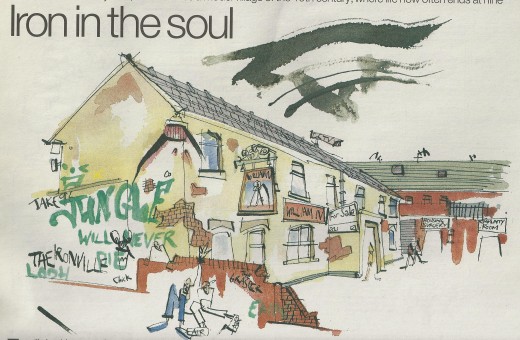

CJ Stone's Britain, Guardian Weekend October 25th, 1997

In the centre of Derbyshire, there nestles a model village of the 19th century, where life now often ends at nine

Ironville doesn't have a very good reputation at all. In fact, it has such a bad reputation that one part of Ironville doesn't even call itself Ironville. It calls itself Codnor Park.

Mostly its reputation stems from itself. The village doesn't need any outsiders to put it down. It does that all by itself. From the moment I arrived people were going on about its bad reputation. They kept warning me to move my van in case it was vandalised. It went on and on. In the end I heeded everyone's advice and moved out of the village.

The village is situated in Derbyshire, not far from Ripley. There's a whole nest of villages there, all running into each other. It's difficult to know when you've passed from one village to the next. I don't know why they don't all give up the pretence and call themselves a town.

I was there at the invitation of the Groovy Movie Picture House, the world's first mobile solar powered cinema. Well I wasn't sure about this. I asked Nancy: "Are you sure you're the world's first solar powered cinema?"

"Um, yes. Probably. Possibly. Maybe. I think so."

So there you go: the world's first probably-possibly-maybe solar powered cinema. At the very least it's the world's first solar powered cinema that I know of.

I turned up of the Friday. The following day it was the Ironville and Codnor Park festival, and Groovy Movies were supposed to be there a day early to set up. They weren't. No one was there. The park where the event was taking place was deserted. I parked up in the carpark behind the King William IV public house, thinking I might get a drink. It was about 8.00pm, and the pub was closed. There were a couple of lads hanging about outside. "What time does the pub open?" I asked.

"Nine o'clock," they told me.

The centre of the village, where the pub is situated, is a modern shopping precinct set around a square. Most of it is boarded up and scrawled with graffiti. The only places that were still doing trade were: a chip-shop, a bookies, a general store and a butcher's. And the pub, of course, though that only seems to trade between nine and eleven at night. The whole village seems to be in a state of slow decline, like a recently bereaved widow who has taken to the drink.

I went to the Anvil Club behind the church where I was introduced to Angie, one of the organisers of the festival. A typical Derbyshire lass, I thought, warm hearted and energetic, with a lovely, rich, kindly Derbyshire accent. That was the best thing about the village, that accent. It made you think of warm, buttered toast.

I asked her why Groovy Movies hadn't turned up. "They told me they would be here today," I said.

"Yes, I warned them not to come today. Not if they didn't want their marquee burnt out, that is. Where are you parked, by the way," she asked. I told her. "Oh no. You'll have to move it," she said. "That's the worst part of town."

Later on - once it was open - I called into the King Billy to ask if it was OK to stay in their carpark. The manageress was a feisty Bette Lynch look-alike, with a back-combed nest of dyed blonde curls piled up on her head and held crisply in place with about a half a gallon of hair-spray. "Where are you parked?" she asked me.

"In the middle."

"Oh no. You can't park there, it'll bring attention to you. You'll come back to find the van splashed in orange paint and graffiti. Either that or they'll take the wheels off. Move it over by the wall. They might not notice you there."

I have to add at this point, that I am now living in my van. It not only gets me around, it's also the roof over my head. Well I don't really want my home splashed in orange paint. Come to think of it, I quite like it with wheels on too. It goes better that way. I took her advice and moved it over by the wall.

I stayed in the King Billy for a few drinks. It really is the saddest little pub I've ever been in. The back windows are all boarded up, the paint is peeling from the plaster, the seats are all ripped, and it's only open from nine till eleven in the evening. There were a few people hanging round on barstools at the bar, and occasionally a couple of teenagers would turn up for a game of pool. One teenage girl, sitting with her mother, warbled out a few spirited renditions of the pop songs playing on the tape. One of them which she particularly liked (and to which her mother added harmonies) was called "Dressed For Success." It seemed a singularly inappropriate sentiment in that decaying, lost little pub.

"Oh no. You can't park there, it'll bring attention to you. You'll come back to find the van splashed in orange paint and graffiti. Either that or they'll take the wheels off"

I was asking questions about the village. It had been a model village in the nineteenth century, they told me, when the forge and the pit had ruled over them. The pit had closed down some time last century, and the forge in 1968. After that there was nothing left for them to do. Tommy was worried about the future, especially about the kids. There was no dignity in the work that was on offer, not like the heavy industry of the past. I asked about drugs. It seemed like the kind of place where drugs might be a problem. There was a bit of it, they told me, but - thank God - nothing too serious.

I went to the toilet. One of the locals followed me in. "They think you're Drug Squad," he told me.

"So you think I'm DS?" I asked, when I got back to the bar.

"Too many questions," they said. "What do you do?"

"I'm a journalist, I told you that. I've come down for the festival."

"Who do you write for?"

"For the Guardian."

"The Guardian!" they hooted. "That's the one all the school teachers read isn't it? Nobody reads the Guardian in this village. Why would the Guardian be interested in a poxy little Derbyshire pit village?"

"Why not?"

But they still wouldn't believe me. I had to take one of them back to my van to show him my files. He brought four bottles of Newcastle Brown with him, which we dutifully consumed. His name was Tommy. "Are you for real?" he kept saying.

"Yes, I'm for real."

In the end he said, "yes, you're for real." The story was so outlandish that he was forced to believe it. He said, "I've got to report back. When I tell them you're OK, you'll always be welcome here."

The following day at the festival Nancy from Groovy Movies was lecturing one of the kids. "You should stay on at school," she said, "otherwise you might wake up one day to find it's too late."

"It's already too late," another of the kids said. He was all of nine years old.

© 2017 Christopher James Stone