- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

Climbing Longs Peak. A Personal Narrative.

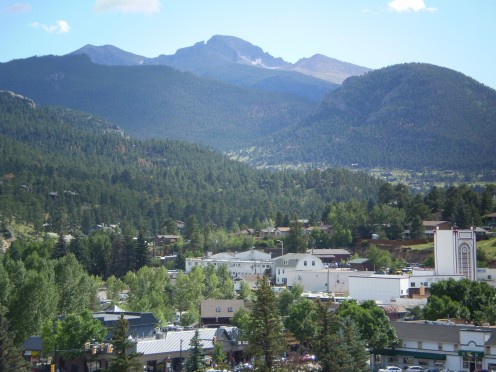

Traveling across the northern plains of Colorado would be monotonous if not for the mountains which form an eye-catching backdrop against the sweep of endless prairie. The eye quickly makes note of the steep twin cones of Longs Peak (14,259’), which rises unapologetically above other peaks. Upon closer inspection, Longs Peak is actually two named peaks: Longs Peak, the higher, and Mount Meeker (13,911’), the closer. These two peaks were called different things by different people. The Native Americans referred to these peaks as The Two Guides; the early French trappers called it Les Deux Orielles (The Two Ears), and early Americans who sighted it in 1820, have long marveled at its unrivalled stature. Eventually the peak would be named after Stephen Long, an American who sighted it in 1820. Today Longs Peak is located in Rocky Mountain National Park, established in 1915 – a beautiful preserve of alpine meadows, rugged peaks, and big game such as elk and bighorn sheep. Although it is only the 15th highest in Colorado it remains a primary goal for both hikers and mountaineers. One look at Longs from any angle and its appeal becomes obvious. This allure has naturally drawn mountaineers and today Longs Peak has no less than 16 named routes, most of them technical which lead the dedicated alpinist to the famously flat summit that’s reputedly large enough to play a game of American football without shortening the standard 100 yard field. It was first climbed by the Wesley Party in 1868 although some claimed to have climbed it earlier but it’s probable they reached summits close by and not Longs’. As an alpinist of the most amateur sorts, I too was drawn to this peak, and in a sort of critical mid-life juncture I planned my climb to coincide with a family vacation scheduled for August 2010. My first sightings of the mountain were much earlier however. I had gone to school at the University of Wyoming in the late eighties and it was possible to see Longs Peak from my dorm window on clear days – about 85 miles south. I never gave much thought of climbing it back then, but as I aged I started climbing more and the lost opportunity of my college days weighed heavily on my decision. Fast forward twenty years and I would have my opportunity.

We landed at Denver International Airport and headed towards Estes Park. Looking up at Longs Peak is sweet candy to the eyes – it’s so high and seems to pierce the skyline like a punctuation mark in bold font. Longs Peak easily tempts speculaiton from the would-be climber and you find yourself benignly figuring which ridge would be easiest to scramble. In fact the people who cut the easiest trail up the peak chose a route which is not technically difficult, providing good weather conditions, but to underestimate even the easiest route can be fatal as it has proved in the past. Exposure, high elevations, and rapidly changing weather are all serious threats that this mountain serves the unwary and inexperienced. Undaunted, I planned on. As my plans took a more solid form, they became more complicated with others in my family wanting to come along with me. Up to this point I was mostly a solitary hiker and I thought it would be fun to have companions. But experience and instinct also reminded me that other people are potential burdens. My reasoning has always been something like this: if I climb alone and don’t reach my goal, usually the summit, I have no one to blame except myself. No worries, I thought, it was my wife and brother – both I knew well, or so I thought. I had hiked a lot with my wife up until ten years before and was pretty confident about her ability. My brother was the wild card, but as an ex-Marine, I figured he could weather this peak as good as any other hiking novice who was fit.

The standard “tourist” route up Longs is the East Longs Peak Trail, which begins at 9400’ on the east side of the mountain. It’s eight miles to the summit and 4,845 vertical feet. Names such as the Boulderfield, the Keyhole, the Trough, the Ledges, the Narrows, and Homestretch seem ominous - almost like obstacles in a fantasy novel that has little hairy-footed men running around to fetch jewelry on high, perilous mountains guarded by griffins and trolls. But the truth is Longs doesn’t release its gremlins until you get to the Keyhole at 13,100 feet. Until then, it’s a rather benign climb through beautiful alpine forests and over meadows. Yellow-bellied marmots are commonly sighted along the way. Once you reach the Keyhole and pass through it you are gripped with a sense of Longs’ other side – its cold, dark face - forbidding, and remote, like a point of no return.

We started early to beat the weather. My main concern was lightning storms that are common this time of year in the Rockies. The weather that week had been fickle and rain moved in every day at around 1 pm often accompanied by the soul-shattering lighting which seemed so arbitrary and unpredictable in its ability to lash out. At half past midnight we started out, apparently the first on the trail. Through the scented fir and spruce we walked, past quiet aspen groves, our path illuminated by our headlamps and a little moonlight poking through scattered cloud cover. Above timberline we could see the hiking parties behind us climbing up toward Granite Pass visible only by the little blips of their headlamps. Just before sunup we reached the well known outline of the Keyhole after a rock-hopping scramble over boulders in the aptly named Boulderfield. The Keyhole is a claw-like rock overhang that is a familiar landmark on the route and a juncture where the trail gets serious. Once through the Keyhole the “trail” gets airy, exposed, and cliff-like, and the need for steady concentration quickly erodes any premature euphoria. It is at this point where you leave the tame face of Longs Peak and the gentle comfort of the meadows that account for three-quarters of the hike to the top. The Keyhole Route, as it is known from this point onward, is marked by bulls-eye circles, a red ring with a yellow center, coupled with tough navigation across and over boulders. Beautiful views of McHenrys Peak (13,327’) and Chiefs Head Peak (13,579’) across the U-shaped valley were slowly illuminated by the soft glow of first light. We scrambled along the rocks and eventually made it to the base of the Trough, a daringly steep pitch that goes vertical until it reaches an elevation of 13,750 feet, marked conveniently by a burnished gold benchmark. Until the Trough I thought we were doing well. I was in good spirits which were occasionally interrupted by my brother’s concern for our descent and an outburst of curses at the path before him. I encouraged him by saying that a hundred people will summit today, of all abilities and some in tennis shoes. “How will we make it down?” – “very carefully” was my response. Let’s just get to the top first, I thought. My wife seemed to be doing well too, until the Trough. But as we climbed up that forbidding sluice-like wall, she too became concerned with my breakneck pace to reach the summit. I slowed down a bit and after some more time waiting for my party things broke down. My wife had trouble breathing and I became concerned. Exertion at these altitudes is a cookbook recipe for disaster. When we slowed and rested she became cold – quickly. Another red flag warning. Eventually we made it to the top of the Trough with many hikers passing us along the way. This was demoralizing as we were at the head of the pack all morning until this point. After a little debate and ambivalence, a few pictures to mark our progress, I decided to head back with my wife and brother. My brother offered to escort my wife back down, but I was worried and fell back on the old climbers’ creed of “stay together”. It was a heart-breaker to be about 500 vertical feet from Longs’ summit and not reach my goal. More insulting to our efforts were some of the naïve “are-we-there-yet” questions we were getting from hikers who we passed while heading down the Trough. Clearly these were novice climbers many of whom probably summitted that day. We finally made it back to the car at 1:45 pm just as a fast- moving electrical storm zapped a nearby tree close to the car park. Over the next couple of days I tried to console myself. Better to have tried and failed than not tried at all. Longs Peak will wait again and next time I’ll know better: what, (or who?), not to bring. Until then, it will remain simmering in the back of my mind.

Other hiking hubs by jvhirniak: