- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

Indiana's 1913 Flood

People in Indiana will tell you that the weather in spring is unpredictable, and can sometimes be deadly. The best example of this is the 1965 Palm Sunday tornadoes. They caused 137 deaths and 1,200 injuries in Indiana. About half a century earlier, another act of nature also caused death and destruction in the state. It became known as the Great Flood of 1913.

Prelude to the Flood

On Friday, March 21, a blizzard hit Indiana and many other states. Wind speeds of 60 miles per hour were recorded in Indianapolis. Cities farther north experienced even stronger winds, with speeds of 86 mph in Detroit and 90 mph in Buffalo. Temperatures dropped below zero across Indiana. In Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, a storm produced tornadoes that killed 48 and injured 150.

The winds calmed down on Saturday, and snow started to melt. Much of the ground was still frozen, and what wasn't frozen was saturated. The storm that spawned the tornadoes in the Gulf states moved northward. On Easter Sunday, March 23, the storm strengthened and brought sleet and high winds to the Midwest. This brought down telephone, telegraph and electric poles and lines. Wireless communication was unknown in 1913, and without wires there was no way for the U.S. Weather Bureau, which had been formed in 1870, to get information about the storm or send out warnings.

On Monday, March 24, the heaviest rains fell. The first storm system moved out while another system entered the state overnight to deposit more rain. In 48 hours, locations in Indiana received anywhere from 3 to 8 inches. Central Indiana is drained by the Wabash River and its tributaries. The west fork of the White River runs through Indianapolis before emptying into the Wabash.

The Flooding Hits

Rivers began to break out of their banks on Monday, March 24. Many cities throughout Indiana were hit hard by the flooding. In Indianapolis, the Morris Street levee gave way on Tuesday, unleashing water that left some neighborhoods ten to fifteen feet underwater. Also on Tuesday, a railroad bridge over White River collapsed. On the next day, the Washington Street Bridge fell into the White River and some factories along the White River were destroyed.

In Fort Wayne, over five thousand buildings were damaged. Downtown Logansport, Indiana sits in a narrow strip of land between the Eel and Wabash rivers. The floodwaters covered the entire downtown area up to nine feet deep, with strong currents. These made it very difficult to rescue people who were stranded. In Peru, Indiana the county courthouse was one of the few buildings that survived the flood. Damage was not limited to Indiana's cities. The floods damaged crops and cropland across the state. Some small towns, like Lyles Station, never fully recovered from the effects of the flood.

There were cars in 1913, but not a lot of them. Henry Ford had introduced the Model T and was using moving assembly lines to build components. However it wasn't until 1914 that he introduced the moving assembly line for final assembly. At this time automobiles were still expensive and mostly restricted to wealthy individuals. Animals were still widely used for transportation and farming. Many people had to evacuate quickly and could not save their animals. The Wallace Circus was in its Peru, Indiana winter quarters. Located near the confluence of the Mississinewa and Wabash Rivers, the area flooded quickly forcing a hasty evacuation. They lost all of their wild animals except for four elephants.

In total, the state of Indiana suffered damages of 25 million dollars. 180 bridges were wiped out, and 200,000 people were forced to evacuate. This was only slightly less than the entire population of Indianapolis at the time.

After the Flood

Water levels crested at two to eight feet higher than previous records. In some cases, the actual levels could not be determined because the gauges were mounted on bridges that had been swept away. This unprecedented flooding caused numerous problems. Rail lines, the heart of the transportation system, were paralyzed due to the loss of bridges over waterways. Water supplies were also disrupted. Many people were stranded without food, water or electricity. To make matters even worse, temperatures plummeted and a blizzard dropped several inches of snow.

In 1913 there was no federal agency to provide disaster relief. States and local communities provided this service, but the flooding was so widespread they were overwhelmed. Indiana and Ohio were hit the hardest, but fifteen states were affected. Dayton, Ohio was hit the hardest. Indiana deaths were estimated to be in the 100-200 range, while fatalities in Dayton were believed to be about 360. Flooding deaths in all affected states were estimated at 650 with another 250 weather related deaths.

President Woodrow Wilson declared the Red Cross as the official disaster relief agency. The Red Cross was primarily a volunteer organization at that time. The only full time staff was at their headquarters in Washington, D.C. They had sixty volunteer staffed chapters scattered throughout the nation. The Red Cross focused the majority of its resources on Ohio, although it also set up a temporary base of operations in Indianapolis.

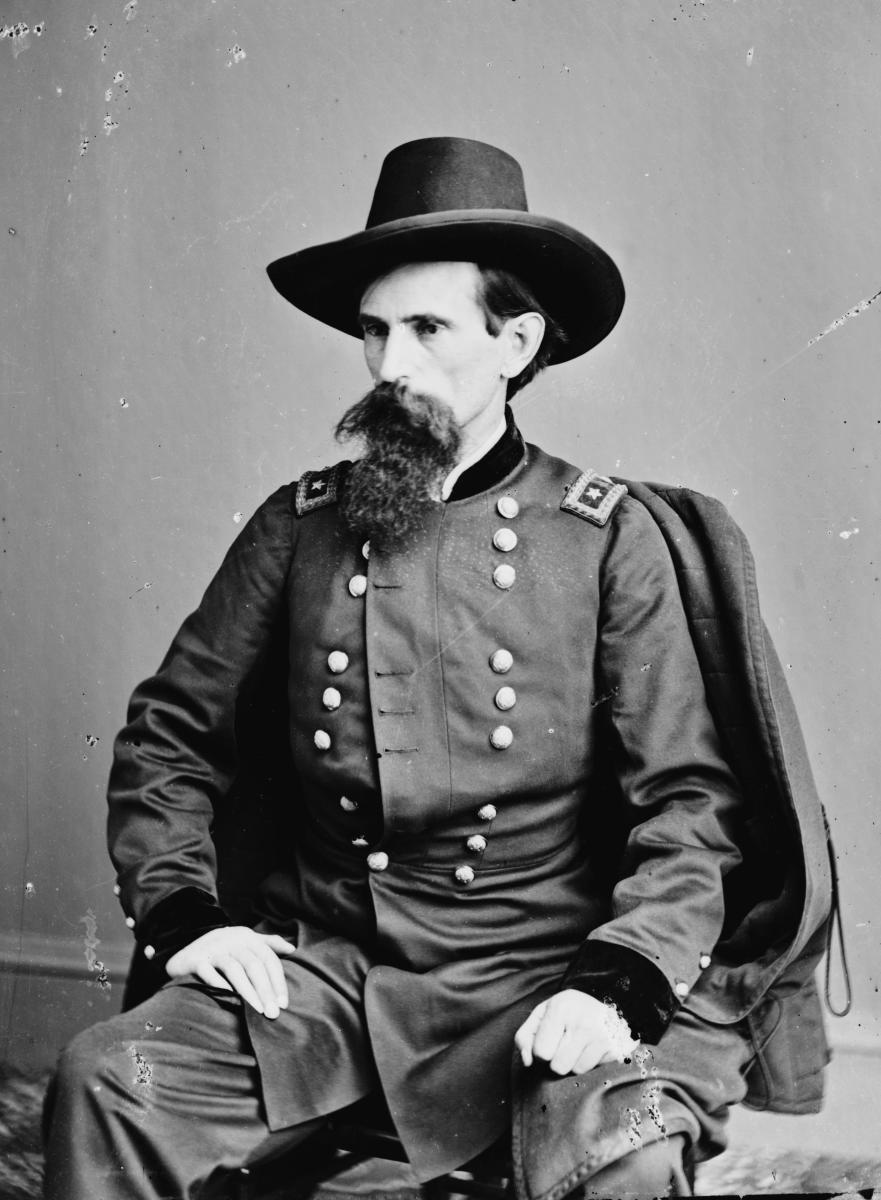

President Wilson telegraphed the governors of Ohio and Indiana, asking what assistance he could provide. Due to downed telegraph lines, Indiana Governor Samuel Ralston never received the message. The first Rotary Club had been formed only eight years earlier in Chicago. The Indianapolis chapter was formed only weeks before the flood. In their first cooperative disaster relief effort, Rotary Clubs across the United States and Canada established a fund for flood victims in Indiana and Ohio. Other organizations also provided relief funds and celebrities assisted with fund-raising.

Rebuilding

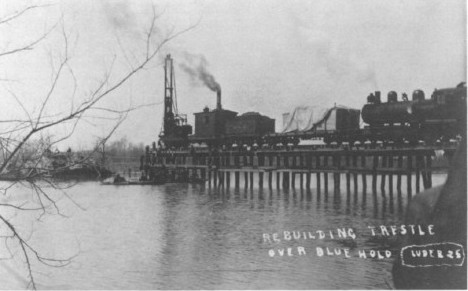

After the floodwater receded, infrastructure was quickly rebuilt, especially railroad lines, which were critical for bringing in food and other supplies. One tragedy that happened during the flood was at a railroad trestle over Blue Hole, a pond near Washington, Indiana. Ironically, this pond was created by a flood in 1875, when water from the nearby White River scoured out the soil. About twenty years later, a trestle was built to take a rail line across it. During the flood a locomotive and two cars from a work train fell into the pond when the trestle collapsed. Four men died in the accident. Within 24 hours, a pile driver was already on site and the rebuilding of the trestle had begun. By April 6, less than ten days after the tragedy, it was operational again. The locomotive was recovered from the bottom of the pond, repaired and back in action by August.