Lessons from My Arab Women Friends

I lived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from September 1990 to July 1994. During the first two years in the kingdom I taught English as a Second Language at the Women’s Language Center in the Thalatine District of the city. I got an up close and personal glimpse into the life these women lived in one of the most restrictive cultures for females on the planet.

Second edition:

My students were very gracious and eager to learn. They loved the exercises I added to the curriculum on vocabulary they might use if they had to take one of their children to an emergency room in the States, or the vocabulary they might use in a western airport, or shopping mall or restaurant – all situations they had either actually been in or could imagine being in one day, Insha’Allah.

They also loved the exercises I made up about American idioms, things like "It's raining cats and dogs" or "I’m scared to death." I loved these too because nine times out of ten they would tell me, once they understood the meaning, they had a similar if not the exact same saying in Arabic. It made all of us feel more the same. or “same – same” as my gardeners would say.

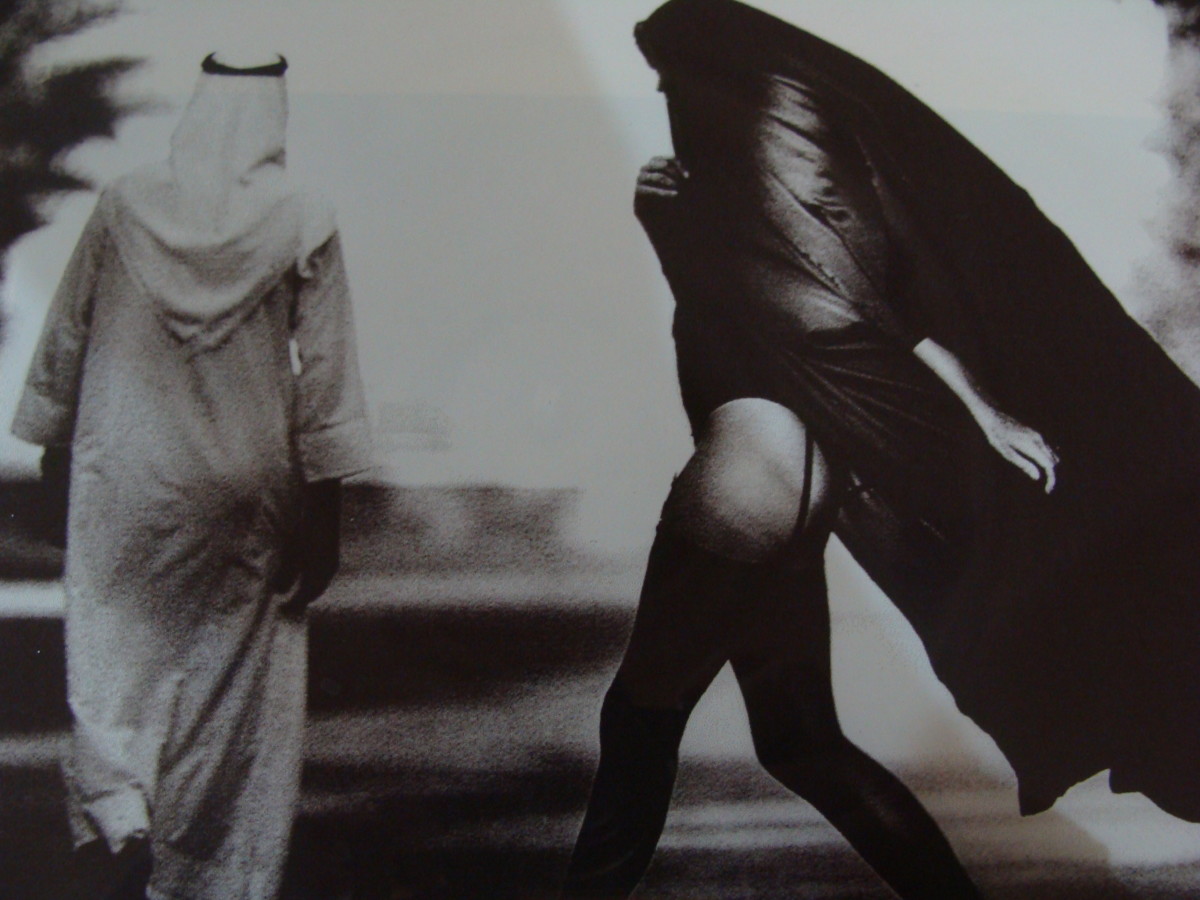

The ladies told me on the first day of class that I looked pretty in my abaya, my black choir robe thing I was supposed to wear over my clothes whenever I went off the compound. On trips to the commissary (the military grocery store), it usually covered shorts and a t-shirt if I wasn’t just wearing a Paki outfit, which in 1990 required no additional covering. But I wore it without fail for the three-block walk to the language school from the compound. And I covered my head. My students showed me how to wrap my scarf like they did. Their way had the added benefit of keeping the wind from blowing the scarf off the way it so easily did if I tied it under my chin like a westerner. I shared this information with my neighbors when we went off the compound, so slowly many of us adapted to some of the native ways.

I covered up in my abaya and scarf for the walk because I was by myself, which is foreboded and might draw the attention of the Mutaween or worse: unwelcome admirers. As I mentioned earlier, a woman alone, especially a westerner, was a woman who was not worth protecting in the eyes of the men there. Whatever happened to her was her own fault or the fault of her family for not looking out for her. I was told of an Arab woman whose engagement was called off because she had been raped. The groom's family would not allow their son to marry into a family that was so careless in the protection of their women. So I covered when I had to be in public alone.

The school was too short a distance from my compound to bother getting a car and driver. So I walked and I walked purposefully. That meant I didn't stop for nothing. (Apologies to my fellow writers.) I also never left the villa without my passport and my U.S. organization’s identification card. If I was stopped by the police, having my passport gave me status. Most ex-pats had to turn in their passport to their employer in the kingdom and only had a copy to show if asked. Also, my passport was diplomatic, not to mention American. It comes in handy to be a citizen of the most powerful government in the world in a place like this. And my I.D. showed my relationship to the organization whose primary purpose was to protect the Saudi King. That didn't hurt either.

The abaya and scarf covered my Sunday Best, which is what I wore to work in a futile attempt to compete with the haute couture of my students. They wore the most amazing gowns under their abyahs with fabulous shoes in an array of colors beyond anything I'd ever seen before. Pre-war, the ladies' abayas stopped above their ankles, showing off the colors of their gowns plus their traffic-stopping high heels. After the war everything became much more conservative, and the bright colors at the bottom of the covering and the pretty shoes went the way of the Dodo Bird. And there must have been a million dollars in jewelry on these women every day. I never saw a woman wear the same jewelry twice. I came to learn that a large part of their wedding dowry was jewelry. I was told the purpose of this tradition was so they'd have something to sell if (when?) their husband divorced them. In the meantime, they showed off their loot like a peacock spreading her tail feathers.

Women dress for each other all over the world, but these women? What else did they have?

My students were full of questions for me.

What did I think about Saddam Hussein invading Kuwait? I had students who fled Kuwait at the time of the invasion and were stuck in Saudi. One of them drove me home after class in her Bentley. Rather she had her driver drive the two of us home. They had family in Kuwait and Iraq and desperately wanted to know how far America would go to rescue them. I had no definitive answers for them. I think they took that to mean that we wouldn’t go very far, but they wouldn’t hold that against me personally.

Did I think women should cover their faces and bodies because their religion required it or because it was the custom of their culture? This question was like asking a Baptist and a Methodist if the Bible says you can drink liquor or not. I would have been more comfortable debating the drinking issue with a couple of Protestants. The women seemed to feel strongly about this issue, with the debate being about fifty-fifty for each side, which in my experience has proved to be pretty much par for the course on most questions pertaining to religion anywhere in the world.

Did I think a bride should talk to her fiancé on the telephone before their marriage? The telephone question really came down to a question of how well you should know the man you marry before the wedding. The option of talking to your intended over the telephone was apparently a relatively new social development in the kingdom. Since 2011 the advent of Facebook has become a driving force in the debate over women in the kingdom being allowed to drive a car. But in 1990 the question of men and women talking on the telephone was an advancement that should have been measured in light-years.

How was I supposed to answer a question like that? When it came right down to it, I was from Mars and these women were from Jupiter. Who was I to give them advice on courtship or marriage? I married a guy I picked for myself when I was a junior in high school. I dated many guys in between meeting him and the seven years later when I married him. Yes, he went through the formality of asking my father for his blessing, but the fact of the matter was we would have married with or without it. And there was nobody to stop me. I’d certainly done a whole lot more than talk to him on the phone prior to our wedding day.

All these women either already had or would have arranged marriages. How was I supposed to relate to that situation and give them answers? I thought for a long minute, then a plausible answer came to me, Alhamdulilah (Praise be to God)! I said I thought it was a good idea to know a future husband pretty well in my culture because I, alone, had the responsibility for picking my own mate. So I'd better know him well enough to make a good choice.

In their culture, their families were responsible for selecting the husband for their daughter, so hopefully they would know a potential mate well enough to insure happiness in the marriage. The ladies seemed pleased with my answer. I should have been a diplomat.

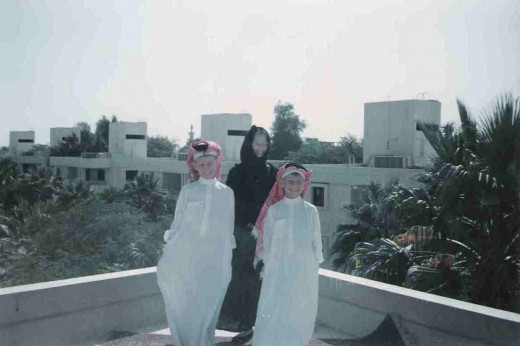

Many of these women had lived in the United States after marriage. One young woman left Saudi Arabia the day after her wedding and didn't return for the next six years while her new husband went to college in America. She established her marriage in freedom and equality. Now that she was back in the kingdom, she was heartbroken by how her marriage had changed. Her husband had no time for her. He never included her in his life as he had while they lived outside the kingdom. What struck me the most about this young woman was that she grew up in this culture. You would think she would know what to expect from her marriage. If it was this hard for her to adjust to the changes in her relationship with her husband after returning to her homeland, how hard must it be for a young, western woman who married a Saudi in America and had no idea what life awaited her when she moved with her husband back to his homeland? Through social engagements with my students, I met several of these western women. Invariably they met their husbands while they were studying in the U.S. and the women were very young and very rebellious. This set of circumstances gave a whole new meaning to later regretting the time you told your parents, “Don’t tell me what to do!”

The most heart-wrenching situation I came across was an American woman who had been widowed and left with two little daughters. A Saudi man enjoying America while gaining a bachelor of science in industrial engineering became enamored of her. She married him and upon his graduation moved to the kingdom with him to establish their new life together. Now not only was she trapped in the Moslem culture, but she’d also trapped her two daughters from their young ages through the rest of their lives. I often wondered if she managed to leave her husband if she’d be able to keep her daughters since the Saudi was not their biological father? But with the average price of a bride being somewhere in the twenty thousand dollar range, you had to also wonder if the money he saved marrying an American wasn’t intended to be augmented by the bride price for the two daughters? Or maybe he really loved her? There was no way for me or you to know. Only the woman could know.