- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

Oklahoma during World War I; with emphasis on LeFlore County

The Early Years

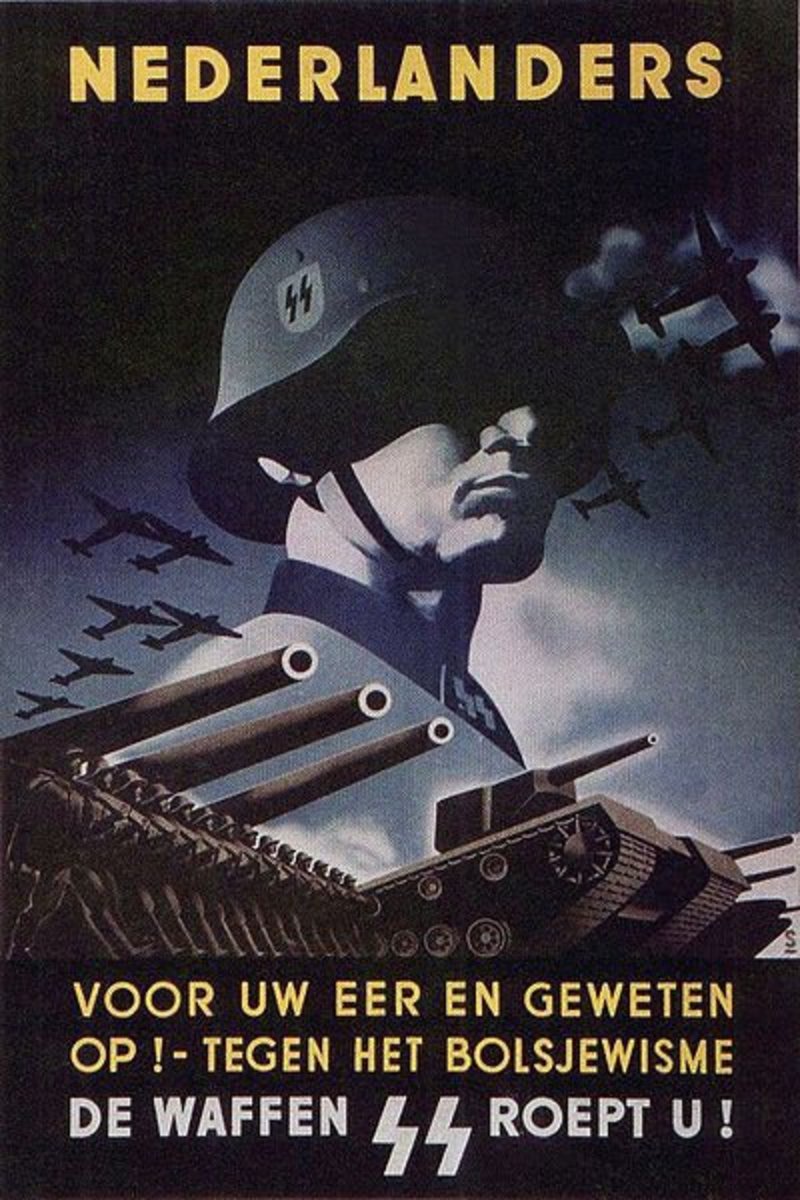

Since war in Europe broke out in 1914, most Oklahoman’s viewed the conflict with an extreme lack of interest. While this was major news, it was considered to be too far away to be of much importance. This indifference to the war became evident when the U.S. Congress passed the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917. The Selective Service Act required that all men of draft age to formally register for conscription on a single day in June of that year. Officials from Oklahoma estimated that the number of draft-age males in the state to be 215,000. Of that number, only 111,986 actually registered. Of those that did register, more than 80,000 claimed to be exempt from service. By the end of that day in June, only fifteen percent of the state’s draft-age men indicated their willingness to fight in the European war.

After American troops began to arrive overseas, Oklahomans began to support the war with a great fervor that hadn’t been seen previously in the state.

Opposition to the War

Some, however, still opposed American involvement. The most dramatic display of antiwar sentiment came in Seminole and surrounding counties in August 1917, when rumblings of discontent with the war led to an uprising known as the Green Corn Rebellion. After seizing control of local institutions, the organizers of the uprising planned to travel to Washington, D.C., hoping to attract enough supporters on the journey to force the federal government to change its war policy. These plans never materialized and the Green Corn Rebellion was easily put down by local authorities.

The Green Corn Rebellion and its aftermath helped spark a backlash against opponents of the war in Oklahoma. During 1917 and 1918 those who disagreed with American war policy were perceived as "radical" and "un-American". The period was marked by unprecedented hysteria and the suppression of dissent.

Developments in Oklahoma mirrored those in other states. Federal officials used the recently-enacted Espionage and Sedition Acts to prosecute nearly eighteen hundred antiwar dissenters. In addition, the federal government created a network of semi-official watchdog organizations called the Councils of Defense to ensure the support of the citizenry for the war.

Among other things, the Councils of Defense promoted the sale of war bonds, distributed loyalty pledge cards, and even reported to authorities the names of citizens who were less-than-enthusiastic in their support for the war. Given the kind of super patriotism created by the Councils of Defense it is hardly surprising that at times the actions taken by these "patriots" took a decidedly extralegal form. Those identified as disloyal were often subjected to rituals of public humiliation (as the man in Comanche County, who was forced to publicly explain his refusal to sign a loyalty card and then to kiss the American flag) or violent intimidation (as happened to Robert Carlton Scott, Carl Albert's grandfather, who was given two hundred lashes by a mob for his refusal to sign a loyalty card).

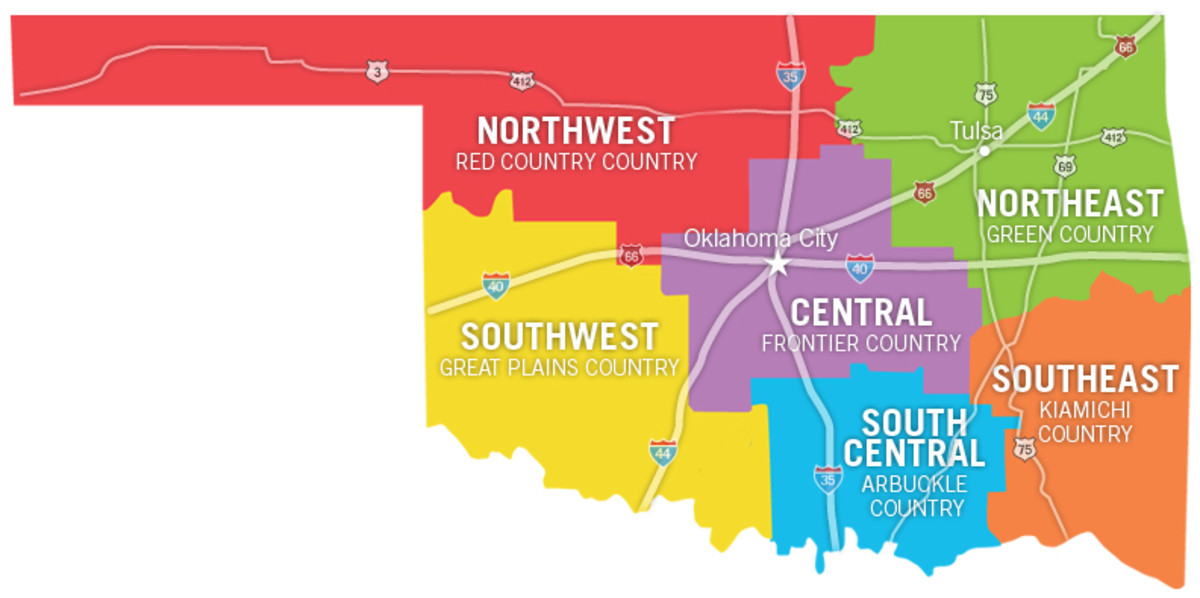

Efforts in LeFlore County

The majority of the residents in Poteau tended to support the war effort.

The county chairman in charge of the Liberty Loans (War Bond drives) was S. J. Doyle. He was assisted by R. G. Bulgin, E. L. Taylor, and David Boal. R. G. Bulgin also served as the Poteau chairman of the Legal Advisory Board, created by the War Department during World War 1.

During the entire period of the war, the board was composed of R. P. White, C. L. Woods, and Dr. B. D. Woodson. Mr. White was the chairman, Mr. Woods was the clerk, and Dr. Woodson was the consulting physician.

End of the War

On November 11, 1918, Poteau residents celebrated the Armistice to end World War I with a spontaneous parade and city holiday. Poteau citizens were awoken early in the morning by the sounds of shouts and whistles. Telephone bells began to jingle and the glad tidings were spread that the armistice had been signed.

Quickly donning street clothes, not even stopping to think of breakfast, they made their way to the downtown district to join in celebrating the great dawn of peace. Grabbing anything that would make a noise they started the grand march through the streets of the city. Like the proverbial snowball, every move meant an addition to the ranks and by the time, daylight broke through the eastern horizon a small army was gathering.

News of the war's end came slowly because of the lack of easy communication. This news first arrived in the early morning, shortly before the sun came up. "My father (William Peck) was out milking the cow when he heard the mother of Dr. Earl Woodson screaming something on the front porch. Father ran to tell mother something had happened at the Woodson home and he was going to see if he could be of any help. When he came close enough to understand, she was yelling the news that the war was over." Within a few hours, the entire town turned out to celebrate. Jim Hopkins made the first speech. Trucks drove up and down Dewey with boilers from the foundry and people beating them with hammers. During the event, people made noise with anything available.

© 2012 Eric and Sierra Standridge