- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

Sand Hills Below the Wyoming Line

Sand Hills Below the Wyoming Line

Henry David Thoreau remarked that he always liked to walk in the direction of the Southwest toward expansiveness and freedom. In that direction the air seemed clearer and more mystical. In mid-June my younger daughter Maureen and I departed our home in Laramie, Wyoming.in a southwesterly direction toward the North Park of Colorado to wander about the sand hills of Jackson County below the Rawah Range near the Wyoming border.

While Wyoming's Snowy Range appeared stormy and dark, Colorado's distant Rawahs gleamed brilliantly in white snow, much whiter than bands of clouds collecting above them. They looked like part of a nether world momentarily in contact with Earth. As we drove toward the wooded fringes of the southern end of the Laramie Plains, the University of Wyoming's Jelm Mountain Observatory sparkled like a day star on the horizon.

We entered the forest above Woods Landing to catch a glimpse of a solitary mule deer standing at the roadside and glancing cautiously at us. We proceeded through angular groves of lodgepole pines lining the roadside interspersed with delicately trembling light-green aspens. Deep in Fox Park, aspen groves attain considerable height; some of the trees with their white bark reminded me of graceful groves of bamboo trees back in Japan where we had lived a few years before.

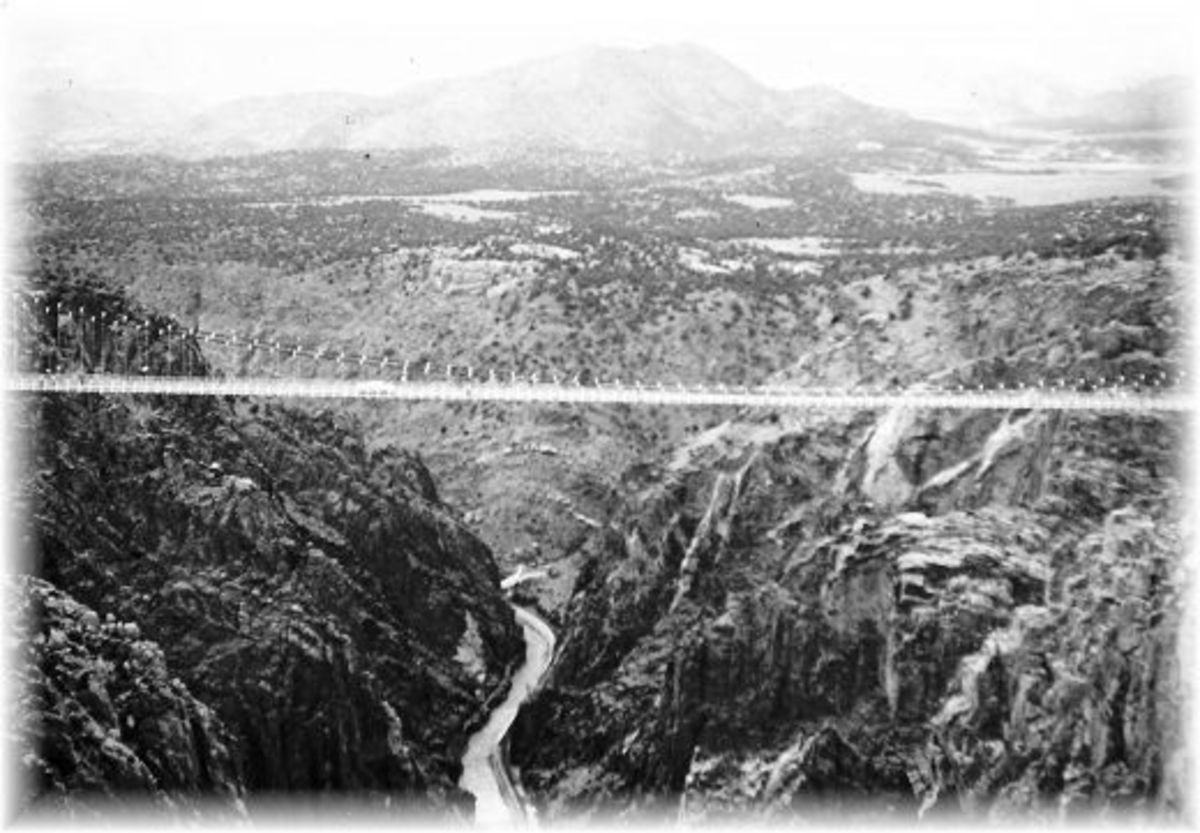

Forest gave way to open sagebrush meadows beyond the Colorado line, and a few more fringes of lodgepole pines held their own against the edge of a big valley called North Park. One high Egyptian pyramid-shaped hill bulged upward with its north side forested and its south side bald. I pointed southward to where winter still lingered in the high country of the Park Range.

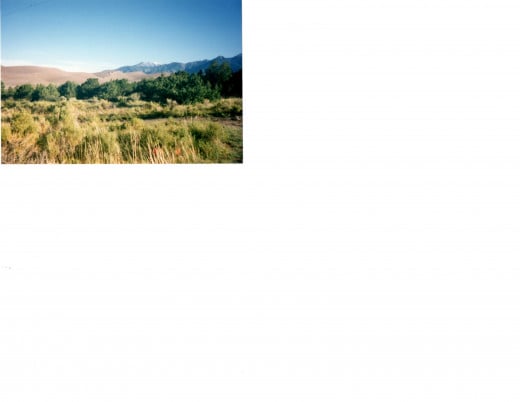

Breezes bent grasses eastward in the wide expanse of North Park. But where are those sand hills? Almost to Cowdrey, Colorado, we saw them, the tips of them, looming to the east just below the Rawahs. We picked a little dirt road to the east and angled our way toward them. We couldn't help but smell the sweet grass growing along the shoreline of ponds. No wonder the Cheyenne Indians make use of sweet grass for sacred incense. Glad to park our car, we got out and walked briskly over sandy hills dotted with sagebrush. Black angus cattle munched on tall stalks of grass beneath the distant Never Summer Mountains blanketed with snow. We ambled along toward aspen-fringed ridges just ahead of the sand hills themselves.

It was relaxing to walk cross country past clusters of flowers bobbing in the wind. Every so often we glanced back at the high Park Range rising to the west. We sensed its presence even after we looked away from the range. After about an hour's hike we arrived at the first of several miles of sandy hills interspersed with patches of aspen, white pine and sagebrush. Once out in the open, we saw scores of animal tracks in the sand including cloven hoof prints of antelope. The tracks made the pulverized sand glisten all the more. We couldn't help but notice many different colored minerals in the sand.

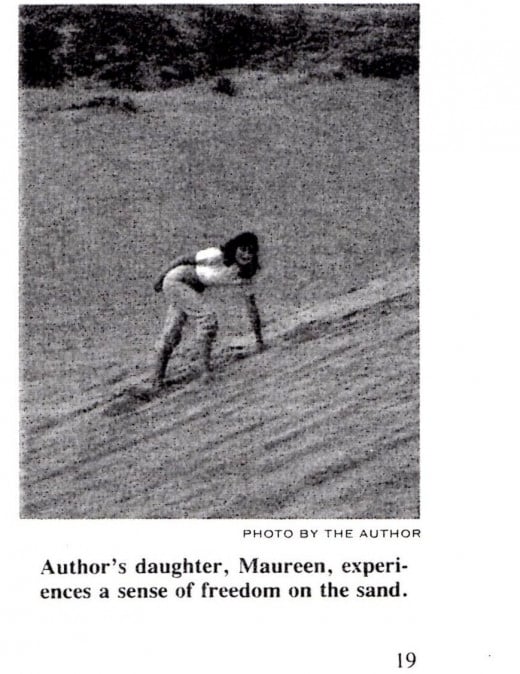

Jay Roberts of the Wyoming State Geological Survey was kind enough to analyze a sand sample that I brought back to Laramie. Here is the result of his analysis: quartz (75.8%), plagioclase (17.2%), potassium feldspar (2.8%), magnetite (0.3%), amphibole (4.0%) and just a trace of sphene (titanium ore). All of these minerals are of igneous or metamorphic origin. Like the Great Sand Dunes of southern Colorado, these hills have formed on the easterly edge of a broad valley surrounded by high mountains eroding their surfaces to the prevailing winds. And, as with the Great Sand Dunes, constant winds push the sand as far eastward as they can into the base of the mountains, sometimes at the expense of trees swallowed alive by mounting sand. Maureen and I noticed that some aspen trees at the northeast edge of the sand hills attempted to grow faster than the advancing sands. Hopefully they will survive.

But unlike a trapped tree, my daughter romped up and down the hills--some more than 40 feet high--feeling complete joy and giggling as she slid down-slope. After a half hour or so, we both continued our exploration of the vegetation trying to fight back the sand's advance. Juniper shrubs , kinnikinnick (a native tobacco used by Native Americans), rabbit-brush and shrubby cinquefoil all shared in resisting the sand.

The sky grew darker and we had to leave this magical place in advance of a storm that was thrashing the Park Range with lightning. Marsh hawks hovered in air currents between mountain and storm. Our minds had truly been ionized by the rare energies of these sand hills. Such sandy rambles are surely needed every now and then.

For those interested in sand dunes, see m hub on the Great Sand Dunes National Park, Colorado, "Our National Parks: Particles of Sand."