The Best Wild Places in the Midlands

A Small Piece of Eden in Birmingham

Sarehole Mill

The Sarehole Plaque

Middle Earth Weekend

Moseley Bog

If you’ve always longed to follow in the footsteps of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins and the other Hobbits, then Moseley Bog offers a fantastic chance to venture into the dark depths of Tolkien’s Old Forest, home of that memorably jovial sprite Tom Bombadil and the lair of the most sinister tree in all of Middle Earth, Old Man Willow. When Middle Earth’s creator J.R.R. Tolkien was just a small boy, he lived at 264 Wake Green Road in Birmingham. For hours upon hours, he and his brother would play around the Sarehole watermill and the neighbouring Moseley Bog. It seems very likely that the adventures young Tolkien and his brother had in the Bog, helped fire his imagination. The fantasies that he spun around the Bog’s willow groves and winding streams on what was then the rural outskirts of an expanding city, later bore fruit in the Old Forest, featured in ‘The Lord of the Rings’.

Sadly, even the young Tolkien was conscious of Birmingham’s ever rapid expansion, and it may have influenced his description of the Shire and the Hobbit way of life, he may have sought to represent rural life as idyllic, while the wheels of industry represented by Saruman and his minions signified the gradual destruction of the countryside.

It’s really quite remarkable how this small dell of thick woodland, ringing with beautiful birdsong and carpeted in bluebells in spring, has survived while Birmingham has expanded around it. Today, if you ever visit, you’ll probably find it hard to imagine how Tolkien gained any sort of inspiration, as the area surrounding the Bog is crammed with houses, shops, roads and busy traffic.

Indeed, the real ‘Shire’ would have succumbed too if it had not been for the tireless work of local enthusiasts in the 1980’s who managed to beat off unwelcome approaches by housing developers, who would have surely plonked their houses there. The narrow, winding paths lead you deep into thickets of alder-carr woodland, past black peaty pools, reed-beds and bog patches. On cold mornings, when the mist fills the hollow, the willows seem almost to move. You can understand the origin of Old Man Willow, and why the young Tolkien was so fascinated by trees and the concept of them being able to move. In the times I’ve been there, I’ve often allowed myself to fantasise the howling of the wind or the shriek of a passing crow to signify the approach of the Nazgul. No wonder the young Tolkien’s imagination blossomed in such a place.

Useful Links

- Sarehole Mill - Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Sarehole Mill is a watermill in Hall Green in Birmingham. This 200-year-old mill is one of only two surviving watermills in the city. It may have been an inspiration for J.R.R. Tolkien.

The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings

The Chase

A Lucky Sight

Cannock Chase

Cannock Chase is a large tract of near wilderness, stretching for over 26 square miles and is often dubbed ‘the lungs of the Black Country.’ This wide area of heath and forest actually lies beyond the northern fringes of the industrial region; it’s always served as a vital recreational resource for the millions of people who inhabit the dozen or so crowded and busy towns and cities nearby. Joggers, cyclists, walkers and families with picnics alike rely on the Chase to give them their own little slice of heaven. Yet, despite this there still remain lonely tracts of heath, boggy hollows and thick woodland that make you feel like you have the place to yourself. The Chase is particularly famous for its resident deer population, which includes the beautiful spotted fallow deer, first brought to England by the Normans and the mighty red deer, Britain’s largest land mammal. The deer are common, but are notoriously hard to spot through their highly developed fear and mistrust of man and his dogs. I’ve never seen any deer in any of my visits (although I have seen plenty of tracks and signs). Unlike the rather docile creatures you can see in deer parks, these beasts are truly wild, so in order to see them you have to work to their schedule. It’s best to go to the Chase early in the morning, preferably just before dawn and make sure that you’re alone, if you have a dog, then leave it at home, as the scent of man’s best friend will quickly drive the deer deeper into the undergrowth.

Cannock Chase’s origins lie with the Bishop of the nearby city of Lichfield, also birthplace of Dr. Samuel Johnson, author of the first English dictionary. The Bishop decreed the Chase as his own private hunting preserve in Norman times. Since then it has been thoroughly exploited. It was grazed and harvested for firewood; then the onset of the Industrial Revolution saw the arrival of iron-makers who set up blast furnaces and felled hundreds of trees in order to feed them. Sand and gravel extraction continued on for centuries. Where the trees were cut, and any new shoots were grazed to prevent regeneration, a broad lowland heath developed. This is the Chase that exists today, a mixture of heather, bracken, silver birch trees, cowberry and bilberry. The county of Staffordshire in which the Chase lies has lost nine-tenths of its heathland in just 200 years. But the Chase fortunately still thrives and is even being reinstated in certain places.

Useful Links

- Forestry Commission - Cannock Forest

The website of the Forestry Commission the government agency charged with looking after the forest. - Welcome to Cannock Chase

Visit Cannock Chase, the official tourism website for Cannock Chase, offers the latest online visitor information and special offers to help you plan your next visit. - Chase Trails - The Mountain Bike Guide to Riding on Cannock Chase

Chase Trails is a website offering all the information you need to ride a bike at Cannock Chase. Mostly for the thrill seekers amongst you.

Images of the Forest

Sherwood Forest

Thank largely to a certain bow slinging hero attired in green, a walk in Sherwood Forest is not only oddly familiar but undeniably romantic. This is a wild place though, that is sadly greatly and poignantly reduced from the medieval days, when Robin Hood and his band of merry men roamed across 100,000 acres of thick woodland cover. This is a woodland that has existed here since the retreat of the glaciers some 15,000 years before; it’s tempting to think that in the days of Robin Hood, this great forest existed as an unbroken mass of trees. But even then, it was a royal hunting preserve complete with farms, commons, scrub and wetlands scattered far and wide among the trees. Much of the forest was actually open woodland, the undergrowth was cleared to allow for easy grazing under the big massive oak trees, which in turn were pollarded or trimmed of their lower branches to allow the pigs and cattle room to wander freely.

In the 21st Century, the great forest is split into several relatively minor blocks of woodland. Just north of Edwinstowe, lies a visitor centre run by the Sherwood Forest Country Park, that maintains some 450 acres, and despite it being much smaller than even in Robin Hood’s time, within these bounds are snippets of grassland and lowland heath that serve as the perfect home for lizards and slow worms. There are also patches of wetland, and of course the tree cover that draws in people from far and wide. At its heart stands the Major Oak, the grand daddy of them all, with a girth of 35 feet, its gnarled 1000 year old limbs now propped up on crutches. Its rather wrinkled and bulky structure gives it the dignity and the awesome presence you’d normally associate with an old bull elephant. It’s thought that the Major Oak is at least 1000 years, but it could be closer to 2000. It certainly well could have sheltered the local bow slinging hero (if he really existed from the Sherriff of Nottingham’s men).

As you can imagine this grand old tree generally attracts a buzz of visitors, so it’s best to take one of the forest paths beyond, putting some distance between you and the swelling crowds. It won’t take long for the silence and serenity to return. Once free of the masses, you can go and seek out and admire the other equally bulbous and charismatic oaks of the forest. These enormous ancient giants provide shelter for hundreds of species of beetles, wood wasps and spiders. Moths lay their eggs on the bark and on the leaves, while woodlice and millipedes thrive on and in the rotting wood. All of these insects help to support more than a dozen species of birds, from treecreepers to woodpeckers that also live in the trees as well as feed in them. The oaks also serve as the perfect home for ferns, mosses and lichens that routinely sprout on or around them. The acorns that drop to the floor each autumn keep the resident squirrels and badgers well fed. They are quite simply the house, the larder and the launching pad for most of the wildlife of this magical, but sadly reduced forest.

Useful Links on Sherwood Forest and Robin Hood

- Robin Hood -- Bold Outlaw of Barnsdale and Sherwood

Robin Hood resources - well-researched historical articles, ballads, interviews, pictures and more for beginners and longtime fans of Robin's legend. - Robin Hood - Nottinghamshire Legend

Everyone has heard of Robin Hood, Nottinghamshire's most famous son and the world's favourite folk hero. His adventures have been retold down the generations, from medieval ballads to Hollywood blockbusters. - Sherwood Forest Trust

Discover Historic Sherwood Forest with visitor information, interactive map and educational resources

Tidal Currents

Profiling the Wildlife of the Estuary

Severn Estuary

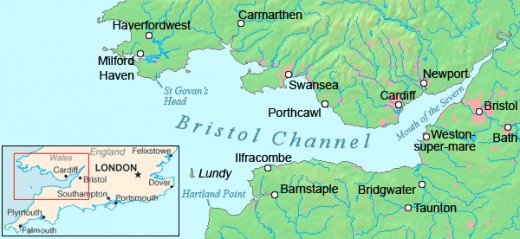

The Severn Estuary is a wild place whatever the tide. As it slowly flows in, you can witness the mudflats and sandbanks disappear one by one under a flood of salt water, prompting the oystercatchers and herring gulls to retreat the muddy margins of the river to resume their gorging of shellfish and other invertebrates. On the ebb, these same features are gradually revealed in a similar way to a theatre curtain opening. There is a constant rush and gurgle as the estuary relentlessly sucks fresh water from the hills and meadows of England and Wales into the Bristol Channel.

This awesome, unstoppable power of nature is best appreciated on the flood-bank footpath that runs upriver from the old Severn Bridge. But in order to gain a grander impression of the frontier between England and Wales, it’s best to step out along the walkway that clings to the shoulder of the bridge as it makes the 2 mile crossing high in the air between the English and Welsh shore. The old bridge was opened in the 1960’s and serves as a graceful link between the two ancient rivals, its two tall towers resembling gateways. You can almost imagine some heroic warrior perched on top, stating proudly to his enemies ‘you shall not pass’. If you gaze southwards, you might catch a glimpse of its younger counterpart, some 4 miles downriver; it was opened just fifteen years ago. A glance over the side of the old bridge shows you the remnants of the landing stage at Old Passage, where cars would queue seemingly forever for the ferry in the days before there was a bridge.

Once on the bridge, you find yourself suspended 120 feet above the water. Only at such a great height does the true majesty of the estuary reveal itself to you. You can gaze properly at the red and white striped cliffs with their vast but shapely curves. The one feature of the River that is diminished when viewing from this great height is a local phenomenon called the Severn Bore, which is basically a salt water surge that pushes up the tidal river and forces its crest high over the out-flowing fresh water; essentially it’s the closest we get in England to a tsunami. In order to be able to savour this local natural wonder in full, you must travel 20 miles upriver to a place called Weir Green at the end of a long, straight stretch of the river, preferably during the night under the illumination of a bright full moon. Normally, a low roar announces the arrival of the bore, followed by a stir in the air and a slapping, sucking noise as the tidal wave rushes towards you. The spray showers you, as the bore sweeps on by relentlessly. It’s truly one of the most awesome sights you can behold anywhere in England, but sadly the bore’s days may be numbered as a huge hydroelectric barrier is already in the advanced stages on conception, as of yet though, the project has yet to commence properly. But the bore is probably living on borrowed time.

A Map of the Estuary

Images of the Dean

Useful Links and Reading Material

- Forest of Dean Tourist Information Official Site

The official tourist website of the Forest of Dean. - THE FORESTER TODAY | NEWS | Nancy's skydive terror as chute fails to open

An independent newspaper that keeps the people of the forest up to speed with the latest news. - Forest of Dean District Council - Homepage

The official website of Forest of Dean District Council

Forest of Dean

It’s often said that what you make of the Forest of Dean depends entirely on what time of year you decide to visit it, and whom you meet while there. In spring, as you can imagine, the forest is a world green with the occasional splurge of blue or white from the wildflowers. It’s a place of light and sound, namely birdsong. In the summer though, it seems to breathe heavily as its small streams begin to run dry and the once vibrant birdsong begins to dissipate. In the autumn every clearing and forest road flickers with the constant fluttering descent of scarlet, crinkly leaves and the grunting of rutting fallow deer. In a cold winter, the forest gains a certain amount of mystery, the frozen ponds and pools creaking ever so slightly and everything else locked in an almost eerie and absolute silence.

The people of the forest, or more accurately the people live in and around the forest are apparently according to their neighbours a rather inward looking, insular and uneasy bunch of people. Apparently, their mistrust of outsiders is substantial, but I have to say that from personal experience that this perception is largely invalid. Like their cousins in the New Forest, they enjoy the luxury of certain ancient laws and customs such as being able to open and work a coal mine, or to graze their livestock, pretty much wherever they want.

The Dean as it’s widely known; covers some 35 square miles with the mighty River Wye and the broad estuary of the Severn serving as two of its borders. Like all of Britain’s ancient woodland, it’s undergone profound changes down the centuries. The coal and iron that lie beneath the thick leaf litter compelled men to strip it of its trees, either entirely or just in part, many times down the ages. The Romans dug here, and so did their Saxon successors. Medieval squatters led a life of poaching, coal mining and cattle grazing with little disturbance from the authorities, while their noble superiors used it as a giant hunting playground. More acres of the forest fell in the quest for iron. At one time, during the English Civil War, the forest’s owner Sir John Winter was felling up to 100,000 trees, and two hundreds year later in the height of the Victorian age, the great forest was stripped virtually bare on more than one occasion. Yet, at the same time, it was also being continually replanted and restocked. There are some rather squat hollies and gnarled oaks that are several hundred years old. Somehow, they have escaped the ravages of man, probably by sheer chance.

In the heart of the forest, is the Russell’s Enclosure and is a good place to go. Enclosures were originally designed to protect precious trees from the teeth of rabbits, sheep, cattle and pigs. Within its bounds are some impressive oaks, at least 300 years old and some rather recent additions in the form of conifers planted in the early 20th Century by the Forestry Commission. The banks of the stream are lined with a lovely collection of typical wetland trees such as willow and alder.

This is a place where frogs, butterflies, dragonflies, birds and insects thrive, as do the fallow deer, a legacy of the long gone Normans who imported them from France. The best thing about the Enclosure is that you can walk ten minutes into it, and then find yourself quite literally lost in the forest.

More Hubs on the Forest of Dean

- Forest of Dean Wild Boar

Following an absence of more than 300 years, wild boars have made a definite comeback to the Forest of Dean and other parts of southern England. Nobody knows exactly how these creatures have come to start populating this rural part of Gloucestershire - Forest of Dean Wildlife

The ancient Forest of Dean has literally been around for thousands of years. It is known that people exploited the oak trees in the area as long ago as 2000 years. Since then, the forest has been subject to a number of laws which were all primarily a

Images of the Malverns

Malvern Hills

In order to appreciate the great majesty of the Malvern Hills, you only have to view them from below. They are hills, but to me anyway seem more like Miniature Mountains, capped with crystalline volcanic granites that are among the oldest in England, maybe as much as 1 billion years old. They rise rather steeply from the flat Severn floodplains, where the counties of Worcestershire and Herefordshire meet. It was once thought that the summit of the Malvern’s stretched several miles into the sky, but today we know that the summit is in fact a mere 1400 feet above the ground. To stand on top of the Worcestershire Beacon- the name given to the summit is truly a life changing experience.

To get the most out of the experience, choose a bright day with lots of wind and a storm gradually building up far off in the distance. These conditions allow you to witness the spectacle that is cloud movement from their perspective. The climb up is short and sharp, so you have to be reasonably fit. Once up, as well as enjoying the view, you can gaze at the toposcope or direction indicator erected in 1897 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The toposcope helps to give you an idea of the scale of everything you can see, and also just how far you can see as well. On a good day, you can see for up to 120 miles in all directions, and gaze across no fewer than fifteen counties. To the east lie the Cotswolds, a series of rolling, fertile hills that stretch from the Midlands, virtually all the way down to London. A turn to the north east allows you to behold Bardon Hill in Leicestershire some 60 miles distant. Turning to the south-west and you see mountains, actual mountains in the form of Wales’ Black Mountains that rise like great natural pillars just over the border. Dead south and you can see as far as Somerset and the hump of the Mendips, which are more than 60 miles distant.

In benign, pleasant weather, it’s views like this that make you want to shout and sing, while on a threatening day, the sheer vulnerability you feel strikes you into dumbfounded silence. I love watching the shadows wax and wane across the land, you feel like the Almighty, almost as if you were in control of everything yourself. The last time I was there, I remember gazing at the Black Mountains, but then my eye was caught by a fast moving cloud depositing its watery load as a sheet on the land far below. It moved relentlessly towards me on the hill, so I made the rather hasty decision to leave my summit kingdom and return to terra firma.

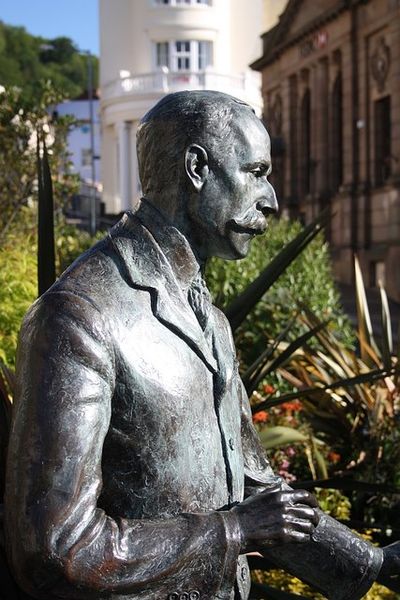

The Malvern's Famous Son

Useful Links and Reading Material

- The Elgar Birthplace Museum and Visitor Centre

One of England's greatest composers, Sir Edward Elgar, was born in this pretty country cottage near Worcester in the heart of England. After his death in 1934, Elgar's daughter Carice set up a Museum here, as her father had wished. - The Beautiful Malvern Hills

Accommodation in the Malvern (UK) locality. - Visit The Malverns

Culture, Heritage and Nature come together in The Malverns. This uniquely beautiful place has more to offer than just landscape, since there is always something happening in the area. - Malvern Hills - the Official site of the Malvern Hills and Commons, managed by the Malvern Hills Con

Conservation and maintenance of the Malvern Hills by the Malvern Hills Conservators. The Malvern Hills Conservators are one of the oldest Conservation bodies in the United Kingdom