Visiting the National Solidarity Monument, Luxembourg: Focal Point of Commemorations Dating From 1971

Narratives, shadows and counterweights revealed and hidden

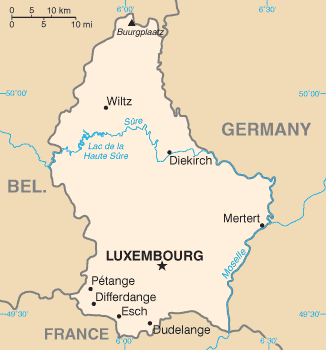

It was a most repressive period involving much suffering for the people of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. It was also a time remembered as involving national solidarity and survival. As such, leaving aside the Luxembourgers who collaborated with the Nazi invaders, virtually all sectors of society are deemed able to engage in commemorations at the National Solidarity Monument (French: Monument national de la Solidarité; Létzebuergesch: Nationalmonument vun der Lëtzebuerger Solidaritéit; German: Nationaldenkmal der Solidarität) in the Grand Duchy's capital, situated at: Plateau du Saint Esprit, L-1475 Luxembourg. Informally, the locality is known as Cannon Hill (French: Colline des Canons; Létzebuergesch: Kanounenhiwwel; German: Kanonenhügel).

The rounded lines of the striking Monument, executed in concrete — with an eternal flame in front of the structure — variously denote prisons, concentration camps and barracks, central structures to the apparatus of oppression brought to the Grand Duchy by the Nazi German invaders.

Responsible for the Monument were sculptor François Gillen (1914-1997) and architect René Mailliet (1915-1999).

Three particular areas upon which commemorations at the Monument focus are the activities of the Luxembourg Resistance during the Nazi German occupation, the endurances of those citizens who were involved in forced labour, and veterans of the armed forces (1). Of notable debate in recent years also has been the perceived role of the lower-ranking Luxembourg authorities in collaborating with the Nazi authorities (2).

Thus, the matters for official commemoration at the Monument are already considerably diverse.

The Liberation of 1944/45 and its aftermath is difficult to commemorate and assess.

This is because, with the forced and highly welcome departure of the Nazi German invaders in 1944/45, there were in practical terms three separate groups which functioned as a government in the aftermath of the Liberation.

Firstly, the Government-in-Exile led by Pierre Dupong, which when it returned to the Grand Duchy in the wake of the Liberation, in some ways found its authority rivalled by the other groups. Unlike during the Imperial German invasion in World War One, the Grand Duchess and the legitimate government had gone into exile rather than be seen to be collaborating with the invaders.

Then, secondly, the Allied Command, led particularly by American forces, as the Battle of the Bulge raged partly on the territory of Luxembourg, exercised what amounted to a de facto civil authority as it continued to pursue its war aims against Nazi Germany. (Within the American camp there were subtleties and factors, of which some of the major players such as Generals Eisenhower and Bradley — both of whom stayed for short periods in Luxembourg — were probably at that time not fully aware, but which had relevance to future developments in Luxembourg.)

Thirdly, militias loyal to Luxembourg's Resistance, given prominence by a number of events during the Nazi German retreat, when the Resistance rather than regular Allied forces took charge of certain localities. These militias, led by Resistance figures among whom were numbered leaders of a strongly Leftist outlook, functioned as a kind of irregular police force.

After weeks of uncertainty in the fog of the continuing war, the official Grand Ducal government felt obliged to incorporate some of the Leftist militia figures exercising de facto authority in Luxembourg. If, by going into exile with Grand Duchess Charlotte in 1940, the Grand Ducal government thought it could preserve its moral authority which Luxembourg's Leftists sought to impugn after the Armistice of 1918, it was soon disabused by the unwillingness of Leftist militia leaders to become quiescent upon the mere return of — by 1944 — long-exiled politicians.

In fact, it was likely that some on Luxembourg's Left would seek to impugn the legitimacy of the legal Grand Ducal government regardless of what it did or did not do in the face of invasion and exile.

It is indeed clear that this process had already begun even before the Imperial German invasion of 1914, let alone the Nazi German invasion of 1940.

While after the Armistice of 1918, diplomatic pressure from France and Belgium combined with disaffected sectors of the Left to ensure the deposition of Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde, disaffection with the Grand Duchess, who began her reign in 1912 at the age of 17, was predated by the Left's disaffection with Grand Duke Guillaume IV, who reigned from 1905 until 1912, and who because of incapacity ceded powers to a Regency of his consort Grand Duchess Marie Anne of Portugal. Marie Anne thus served in that capacity from 1908 until 1912, once her daughter Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde has reached her majority after inheriting the Grand Ducal throne earlier that year (3). So it was that before World War One many on Luxembourg's Left were totally disaffected with: i) Grand Duke Guillaume; ii) Regent Marie Anne; iii) Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde.

With the advent of World War One and its resultant, extreme upheavals, many on the Left were in no mood to accept the continuance of Marie-Adélaïde as Grand Duchess under any circumstances (4); a short-lived or even still-born republic was proclaimed.

Thus, with the advent of World War Two and the excruciating experience of Nazi German invasion, there was already a long history of some on the Left seeking to some extent to discredit the institutions of the Grand Duchy. It may be argued also that it was practically inevitable that after Liberation some on the Left would seek to use commemorations of the painful 1940-1944/45 occupation period as leverage for their professed ideological concerns.

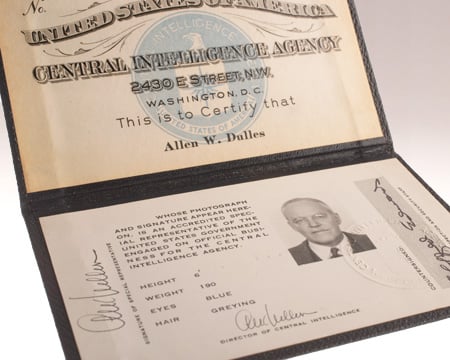

But interestingly, even as many on the Luxembourg Left have moralized, it has been noted that in World War Two Leftist figures such as Pierre Krier (1885-1947)(4) solicited money which was supplied via leading OSS figure and later Director of Central Intelligence Allen W. Dulles (1893-1969), with Luxembourg trade union leaders Pierre Clement and Antoine Krier acting as trustees of funds. This money, from AFL - CIO, while ostensibly in solidarity with and for the support of underground labour movement in Luxembourg and the other Benelux countries, was actually for other purposes. Geert van Goethem has written: 'It was clear from the outset that the money was going to be used for military purposes ... and that the humanitarian aspect was only a cover' (5). While the fog of war can understandably lead to strange bedfellows and highly pragmatic actions, this episode does beg questions about how some prominent figures on Luxembourg's Left could be willing to become indebted at least indirectly to a resolutely unsocialist personality such as Mr. Dulles, and all he was later perceived to stand for, even as figures on the Left moralizingly found fault with conduct of their more conservative patriots during World War Two.

It is interesting also that in the late 1940s the same AFL - CIO was used — again, by the same Mr. Dulles, by now in the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), through the American Committee on United Europe (ACUE), chaired by General William J. Donovan — to fund promotion for the European Coal and Steel Community (6). Indeed, former OSS head General Donovan was a particular supporter of the Schuman Plan for the Coal and Steel Community devised by Luxembourg-born Robert Schuman (1886-1963)(7).

One can therefore see how the Occupation and Liberation period during and after World War Two was characterized on the disparate Allied side by an intense variety of ideological and influences, the nature and abiding relevance of which were in some cases to be revealed only years later.

Be this as it may, the National Solidarity Monument has become somewhat of a showcase to foreign dignitaries. These have included Russian leader President Putin. Here, too, hidden complexities emerge, when one looks at the history of the Grand Duchy's relations with Russia. The Grand Duchy has had special relations with Russia since the era of the Czars; these in a measure continued during the Cold War years, with the then Soviet and now Russian Embassy housed in the Château de Beggen being one of Luxembourg City's more well-staffed diplomatic missions. It is interesting to reflect that the East-West United Bank in Luxembourg was a significant Soviet earner of hard currency. There is a sense in which Luxembourg's relations with Russia have come full circle in 100 years: while Russia under the Czars was an autocratic power, in the Soviet era its autocracy was coloured by radical rhetoric, and today Russia would be widely regarded as some sort of conservative force in international politics; and thus also relations with Russia have run the ideological gamut of the various conflicting ideologies present within the opposition to Nazism during World War Two.

If indeed the emphasis of the commemorations around this Monument can ostensibly focus on the moral rectitude of those who suffered in a common national cause, then the nuances — some of them disturbing? — can thus perhaps remain in the shadows. Whether some of the historical light shed on these shadows and nuances leads inevitably to — or is even being driven by — what is professed as the goal of national solidarity, is perhaps itself open to nuance.

May 27, 2019

Notes

(1) See also (in French): https://gouvernement.lu/fr/gouvernement/etienne-schneider/actualites.gouvernement%2Bfr%2Bactualites%2Btoutes_actualites%2Bcommuniques%2B2015%2B10-octobre%2B08-journee-commemoration.html

(2) See also: (in French): https://www.wort.lu/de/politik/vincent-artuso-repond-a-charles-barthel-un-temps-deraisonnable-563399730da165c55dc4c45f ; (in German): https://www.wort.lu/de/politik/die-judenfrage-in-luxemburg-meilenstein-oder-stolperfalle-5617ee1a0c88b46a8ce61e76

(3) By 1912 Luxembourg's Left was generally disaffected with Regent Anne-Marie's views on schools and on her perceived closeness — with her background as a member of the by then deposed Portuguese royal family — to the Roman Catholic Church. Ironically, her reigning consort, Grand Duke Guillaume IV, was a Protestant.

(4) Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde was seen by many on the Left to be tainted with perceived fraternization with the Imperial German invaders.

(5) Geert van Goethem, The Amsterdam International: The Work of the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), 1913-1945, Aldershot, England / Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate Publishing, 2006, p. 273.

(6) Aldrich, Richard J.(1997) 'OSS, CIA and European unity: The American committee on United Europe, 1948-60',Diplomacy & Statecraft,8:1,184 — 227 10.1080/09592299708406035 ; http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09592299708406035 ; https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/aldrich/publications/oss_cia_united_europe_eec_eu.pdf

(7) From 1990 Luxembourg has hosted Le Centre de Recherches européennes Robert Schuman (Robert Schuman European Research Centre), first housed in the birthplace of Robert Schuman who later served as French Prime Minister and Foreign Minister at a pivotal period following World War Two. The founding director of this Centre was Professor Gilbert Trausch (1931-2018), under whom I was privileged to study a number of decades ago, and whose passing in 2018 removed a distinguished figure from among scholars of the history of Luxembourg.

Also worth seeing

In Luxembourg City itself, visitor attractions include: the Pont Adolphe over the picturesque Pétrusse Valley; the Grand Ducal Palace; Place Guillaume II , the Gelle Fra monument; the Cathedral.

..

How to get there: From Luxembourg Airport (Aéroport de Luxembourg ), at Findel, car rental is available. For North American travellers who make the London, England area their touring base, airlines flying to Luxembourg include Luxair (from London Heathrow Airport and London City Airport). Please check with the airline or your travel agent for up to date information. You are advised to refer to appropriate consular sources for any special border crossing arrangements which may apply to citizens of certain nationalities.

MJFenn is an independent travel writer based in Ontario, Canada.

Other of my hubpages may also be of interest

- Visiting the Chapel of Saint-Quirin, Luxembourg City: ancient church building cleft in the rock

This remarkable Medieval chapel is striking not only for its origins many centuries in the past but also because of its location: cleft in rock in Luxembourg City's Pétrusse Valley. Some history and features This chapel is... - Visiting Natzwiller, France: sober remembrance of World War Two inhumanity

25,000 people are said to have perished at this concentration camp on French soil, functioning between 1941 and 1944. 25,000 people. Albert Speer, later Hitler's production supremo, was linked with it