- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Animosity, Division and Hatred in Civil War America - Part 1

Henry Washington Younger moved to Harrisonville Missouri, not far from the border of the Kansas Territory, with his wife Beersheba and their twelve children in 1857. Already a successful businessman, by 1859 he became the second mayor of Harrisonville. Henry Younger was working for the Federal government in 1862 as the holder of a mail contract for 500 square-miles around Harrisonville, and while away on business in Washington, Henry’s store was looted and then destroyed by Kansas Jayhawkers who also raided the livery stable and stage lines. When Henry returned, he set off for Kansas City in an attempt to correct the matter with the State Militia but on July 20, on his return, he was shot three times in a politically motivated murder south of Westport Missouri, allegedly by a Captain Irvin Walley of the fifth Missouri Militia Cavalry. He was not robbed and was left where he died, his horse tied to a tree1 Henry’s son, Coleman Younger, vowed to avenge his father’s death and, along with his brother-in-law John Jarrette, joined a company commanded by Captain William Clarke Quantrill.2

The western border of the United States was not the only place beset with animosities between American citizens. Brothers Andrew K. and William Shriver lived in Union Mills, Maryland, across the road from each other. When the war Civil War broke out, Andrew, who owned a few household slaves, took sides with the Union while brother William sided with the South. William owned no slaves.3 In 1863 when Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart arrived in Union Mills, he stopped at Andrew Shriver’s home for lodging and provisions, but Andrew Shriver sternly turned Stuart down. In the morning, General Stuart paid a visit across the street to William’s home, where the general was greeted with open arms. Later in the day, Union troops arrived with the opposite effect on both brothers. In the morning, those twelve thousand troops marched off to Gettysburg.4

The animosity and division present in both Missouri and Kansas, prior to and during the Civil War, that led to guerrilla warfare in both states was a representation of the divide gripping the entire nation, pushing it towards inevitable war.5 Slavery, economic, social and political differences, were examples of the situations Americans found themselves confronted with which motivated brothers to fight brothers both in Missouri and Kansas as well as across the nation. This led to the use of guerrilla warfare, as opposed to conventional warfare. The men who fought as guerrillas in Missouri and Kansas fought this type of warfare because of the combination of motivational factors, locality, and cultural norms.6 These factors directly represented the mood of the entire nation.

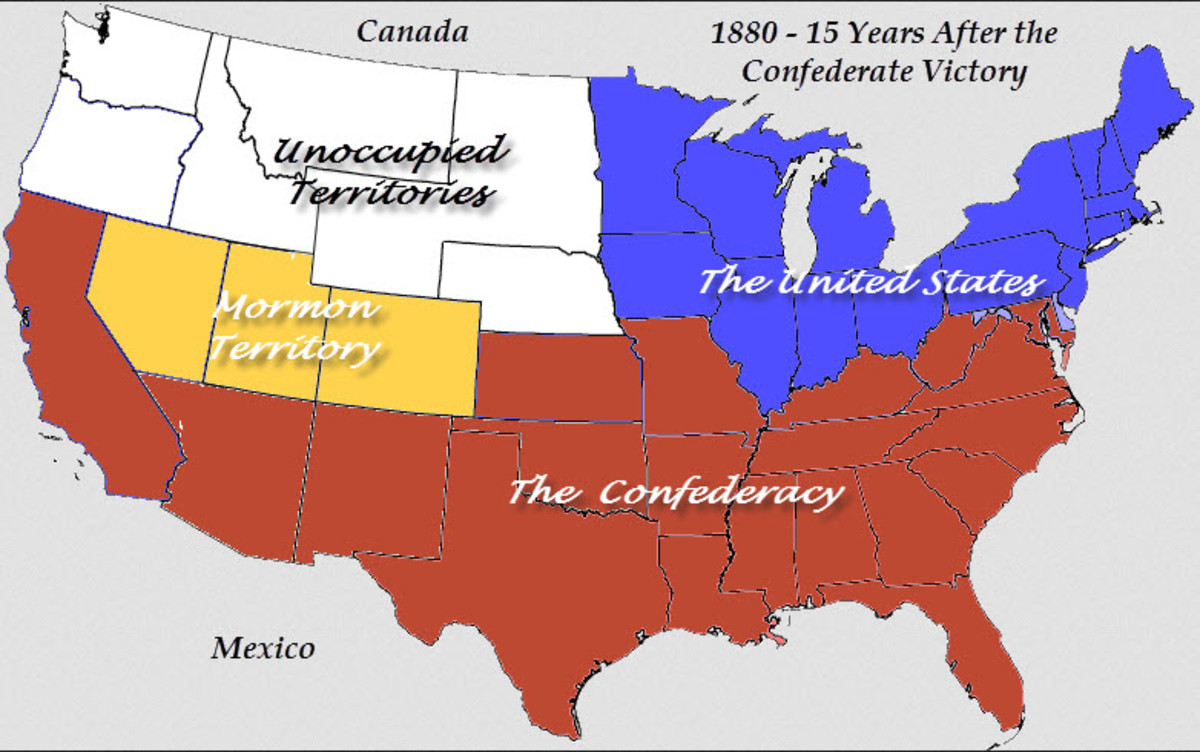

In order to understand the similarities in attitudes in bother the western frontier of Missouri and Kansas as well as that of the rest of the nation, we need to look at the nation as whole and the define the factors of division. The Northern and the Southern States were quite different culturally, economically and politically. James McPherson describes the view of both cultures in antebellum America, in that the South was that of “a gemeinschaft society, with its emphasis on tradition, rural life, close kinship ties, a code of honor and chivalry” in contrast to the North as that of “a gesellschaft society, with its impersonal, bureaucratic, meritocratic, urbanizing, commercial, industrializing, mobile and rootless characteristics.”7 These two very different views of culture only found itself more exacerbated by the South feeling threatened by the change being forced on them by the North and the North’s feelings that the South was backwards in holding this fear of change. Moreover, of course, the peculiar institution of slavery was “the engine that drove the southern economy and the southern way of life.”8 The industrialized and urban North had little use for slavery, and immigration German and Irish immigrants provided a stream of willing workers. The agrarian South, however, relied almost solely on the backs of its slaves for its work and profits.

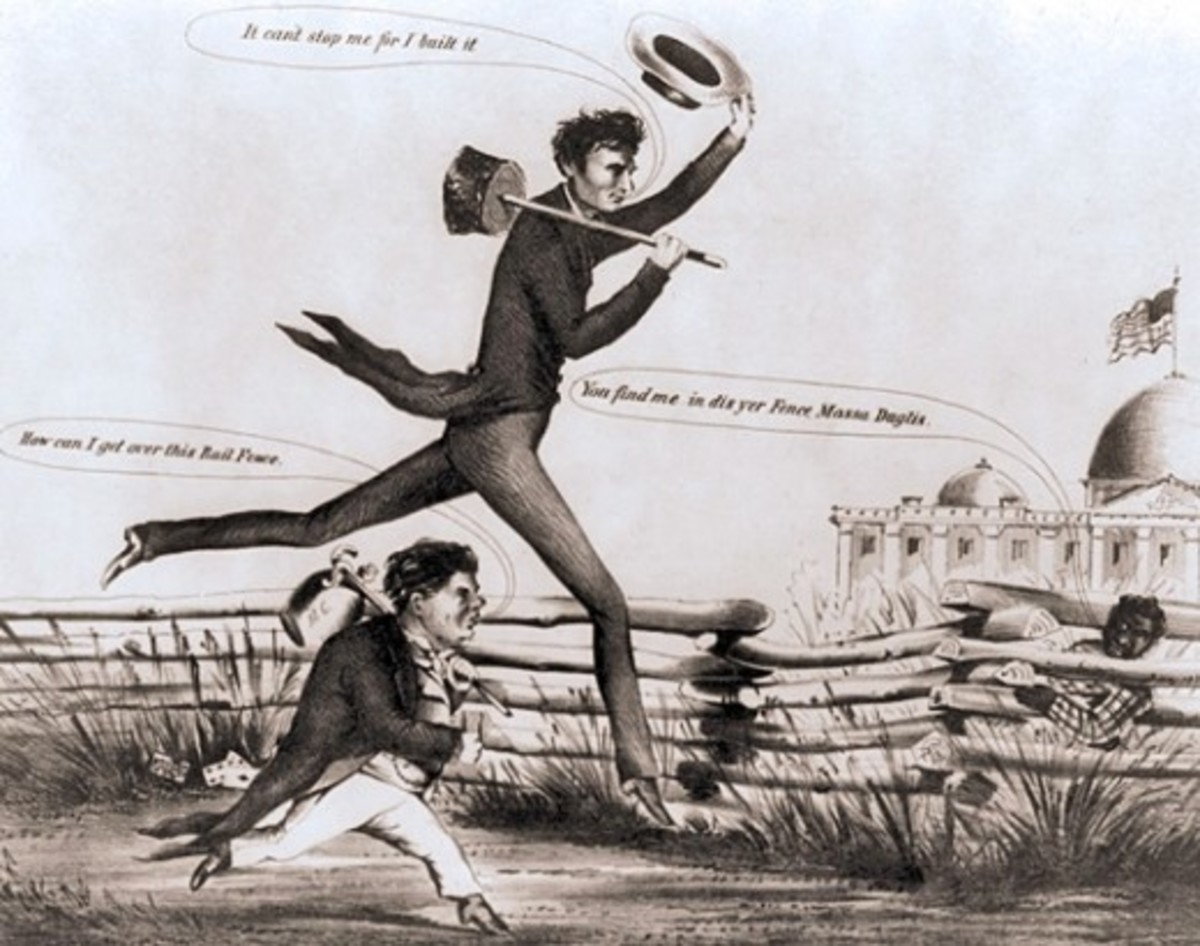

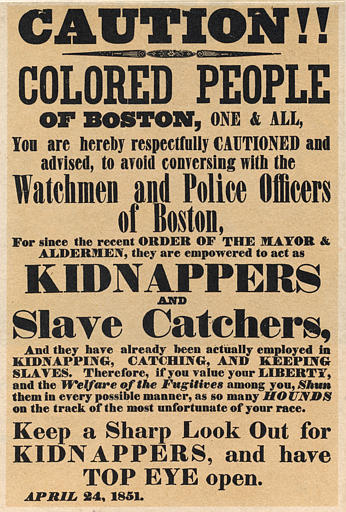

Slavery was like a bad tooth, and nothing aggravated that tooth more than the Fugitive Slave Act. There had been other incidents prior to the Fugitive Slave Act that had begun polarizing the United States. Even as early as the drawing up of the U.S. Constitution, the Federal government leaders were very aware of the sensitivity slavery presented to the fledgling United States, but conveniently passed the issue on to future generations. The Northwest Ordinance was put into effect in 1787 in an effort to regulate the areas north of the Ohio River, and as Paul Calore states,

it easily gained the approval of Congress on July 13, but in deference to the South the new law also contained a third provision, a stipulation that all slave owners had the right to reclaim their fugitive slaves.9

There was no real method of enforcing the law, and Southerners grew concerned over what they considered a weak position by the Federal government. The Second Congress then enacted the first Fugitive Slave Act in 1793 in the face of continual pressure from Southern political leaders. This edict was much more precise, and most of all, to the delight of southern slave owners, legally binding. The new law allowed the slave owner unrestricted right to retrieve his property, deliver it to any magistrate in order to prove his ownership, and made it a crime to interfere with the recovery of runaway slaves.10 It was personal liberty laws such as the Fugitive Slave Act, born out of vagueness of the Constitution on the details and legalities of whether the return runaway slaves were the responsibility of the state or the Federal government officials. This ambiguity caused rifts between antislavery groups and slave owners as to how slaves were captured and returned versus the Fugitive Slave Act's flimsy procedural safeguards to sell large numbers of blacks into slavery.11

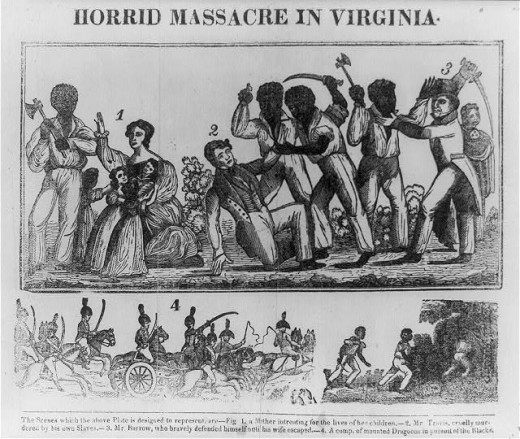

With slavery now sanctioned by the government, northerner began forming anti-slavery societies promoting a vocal and physical abolition of slavery. In 1831, a slave rebellion led by slave Nat Turner, that was precipitated by a pamphlet released by David Walker in 1829 urging the uprising of slaves, ended with the deaths of sixty whites and the rising up of mobs that began attacking and killing blacks. Turner and 16 other slaves were quickly executed. The entire affair seemed to bolster the southern position that blacks were a danger if allowed their freedom and that the abolitionist movement was a danger to society.12

However, this did not stop the abolitionist movement. In 1833, William Lloyd Garrison formed the American Anti-Slavery Society which rose to nearly 250,000 and took a proactive approach to combating slavery. I ran safe houses on the Underground Railroad, went up against immigrant mobs, angry that slaves would take their jobs and campaigned vociferously, to the point they were found “distasteful to polite northerners, even those who shared their two beliefs – that slavery was a sin and that everyone was their brother’s keeper.”13 There had been other attempts to address the now out-of-control issue of slavery in America. The Wilmot Proviso in 1846 was such an attempt.

This proviso was an attempt to end slavery in the areas that would be acquired at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot attempted to insert an amendment into a bill that was aimed at appropriating money by the terms of the treaty. His amendment, which stated, “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall be first duly convicted,”14 was blocked by the southern dominated Senate accomplishing nothing more than further igniting the growing sectionalism.

You can continue to Part II by clicking HERE

How influential do you believe slavery was to the sectional conflict in 19th century America?

Sources

[1] Coleman Younger, Story of Cole Younger: By Himself , (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000), 4-5.

[2] Ibid., 16.

[3] Andrew Borsa, "Divided Families: The Shriver Brothers of Union Mill." Crossroads of War, accessed December 1, 2015, http://www.crossroadsofwar.org/discover-the-story/communities-at-war/civil-war-stories/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Many books have been written about the divisions present in American leading up to the war as well as during the war, such as James M. McPherson’s For Cause & Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, David M. Potters The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War 1848 - 1861, and Paul Calore’s The Causes of the Civil War: The Political, Cultural, Economic and Territorial Disputes Between North and South are to name but a few.

[6] Or as author and historian Michael Fellman stated in his book Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri during the American Civil War, “the war of ten thousand nasty incidents” (251)

[7] James M. McPherson "The Differences between the Antebellum North and South," In Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction, by Michael Perman, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), 24.

[8] Paul Calore, The Causes of the Civil War: The Political, Cultural, Economic and Territorial Disputes Between North and South, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), Kindle Edition.

[9] Ibid.

[10] United States Congress, "The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793," In The Constitution of the United States, with Acts of Congress, Relating to Slavery: Including the Nebraska and Kansas Bill, by D.M. Dewey, (Rochester: D.M. Dewey, 1854), 16-17.

[11] Norman L. Rosenberg, "Personal Liberty Laws and Sectional Crisis: 1850-1861," Civil War History 17 (1971), 26.

[12] William C. Davis, The Civil War: Brother Against Brother - The War Begins, (Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1983), 40.

[13] Ibid., 62.

[14] David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis 1848-1861, (New York: Harper Perennial, 1976), 21.