- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Animosity, Division and Hatred in Civil War America - Part 3

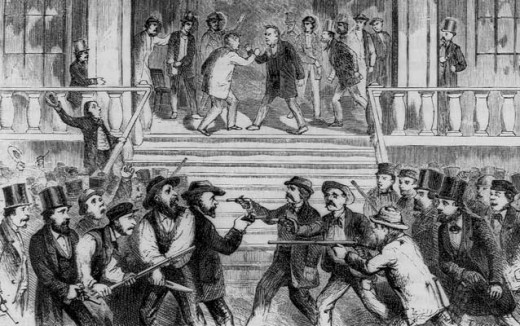

Author and historian Bruce Nichols presents his argument that there five motivations for men to take up arms against their fellow countrymen, neighbors and even family. These reasons not only account for the guerrilla fighting on the western border, but as well as the rest of the nation. Along the border of Kansas and Missouri, however, there were few large-scale battles involving organized Union and Confederate troops, but the reasons for fighting were the same. Most of the fighting took place in unassuming places with no planning or strategy; tempers flared and bullets began to fly. The first reason is that many fought out of bitterness. Union General John M. Scofield claimed that “…the bitter feeling between the border people, which feeling is the result of old feuds, and involves very little, if at all, the question of Union or disunion.”1 Many of those in Kansas and Missouri were at constant struggle with each other over the issues of slavery and the expansion of the nation. This was no different than that of the other southern states. Missourians felt that they or their friends and relatives, had been done wrong, and were bitter over the idea of being shielded behind the Federal government.

Guerrilla Samuel S. Hildebrand explained that,

The necessity that was forced upon me to act the part I did during the reign of terror in Missouri is all that I regret… it has caused my kind and indulgent mother to go down into her grave sorrowing; it has robbed me of three affectionate brothers who were blatantly murdered in their own innocent blood; it has reduced me and my family to absolute want and suffering, and has left us without a home, and I might also say, without a country.2

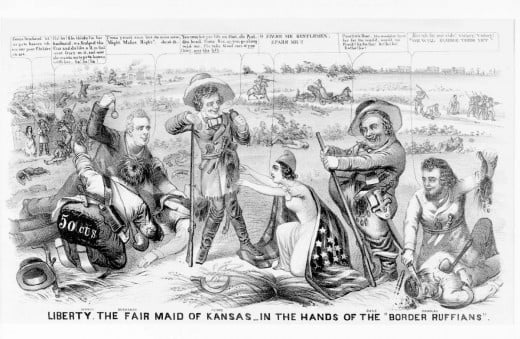

Southerners felt the same experiences. The late Shelby Foote explains in the Ken Burn’s documentary “The Civil War” how upon capture, a Union soldier asks one of the Confederate men why they were even fighting this war. His response is an echo of the border conflicts in Missouri and Kansas – “I’m fighting because you’re down here.”3 Vengeance and one’s position for or against slavery was one of the motivations that created a bitterness between the nation and its people and caused them to take up arms against each other. With the years of violent murder and blood soaking the soil of the Kansas Missouri border prior to Ft Sumter, the admittance of Kansas as a free State fueled the quest for purging the nation of slavery, but also, to punish Missouri for what Kansans believed were atrocities posed against them. Kansans envied the fertile and provisional lands along the border in Missouri and because of a drought between 1859 and 1860, found the eve of Civil War a perfect catalyst to cross the border and satisfy both their vengeance and covetousness.4

Anger compelled many men to take up arms and fight against each other. For southerners, President Lincoln’s call for volunteers to suppress the southern rebellion was a direct affront to them; that their own government would, by force, subject them against their will, the extremism of the abolitionists, sensational southern press and harsh tactics such as the draft, impressing private property for military use and enforcement of civil law.5 From a Northern perspective, the people who were against secession viewed the southerners as traitors. It angered them that southerners had the audacity to challenge the government. A young Philadelphia printer echoed the rest of the pro-Union sentiment; “This contest is not North against South…It is government against anarchy, law against disorder.”6 But unfortunately, this disorder and lawlessness was perpetrated by both Union and pro-southern officials and citizens. Mrs. Martha F. Horne lived in Cass county Missouri and explained how four of her slaves had run off in the night taking horses and provisions after her husband had gone off to war in 1862. She was left behind to face Jayhawkers, who took what little they had left that had not already been taken by the Redlegs or Union militia, including the negroes, horses, wagons, supplies and all. Upon arriving in Lawrence Kansas, she was informed that all of those supplies were robbed by Redleg’s and the Negroes were left to “root hog, or die.”7

Hope was another factor for both the northerners and southerners, and both sides of the equation viewed their cause as the superior cause. Southerners clearly felt they were fighting an invading force. They were also fighting for their God given and Constitutional right to their property; slaves. Northerners on the other hand, truly believed that they were fighting to save the Union and that in doing so, and possibly sacrificing themselves, the experiment started by the Founding Fathers would continue and not be in vain. There were abolitionists, however, who fought to end slavery, and while they were not in the majority, they played an instrumental role in perceptions of the division in the country in regards to slavery. Many of these men, such as Daniel Anthony and George Henry Hoyt drew the ire of Union men simply with their unrelenting abolitionist rhetoric. But these men would eventually take part in a very violent point in the war in Missouri during the depopulation of border counties in Missouri. General Order No. 11 issued by Union General Thomas Ewing Jr. was enforced by the Red Legs, scouts sanctioned by the Union Army, under the command of Hoyt who “resolutely, inflexibly, and at all times, under all circumstances, fight slavery.”8 In line with the concept of hope, patriotism was another example. The hope and belief in something bigger than themselves. The French call the initial impulse to fight rage militaire – a patriotic furor that overcomes people at a time of national crisis.9

Desperation, especially in Missouri and Kansas, was a huge factor. Even before the first shot rang out at Ft. Sumter, regular, everyday citizens, who quite honestly preferred to just stay out of the whole mess of politics and remain neutral found themselves without a choice. When Lincoln made his call for volunteers it wasn’t just to bolster the Union Army, it was to weed out the wheat from the chaff. Men who did not enlist in either army found themselves harassed to the point of death by both Union and Confederate Home Guards. The late historian Michael Fellmen wrote that “As the war evolved, neither guerrillas nor Unionists permitted neutralism, seeing it as a service, however meekly given, to the enemy.10

The final motivation that Nichols provides is excitement. Young men went off to war and viewed that their fighting would bring them personal glory. Down in Arkansas, Henry Crawford and five others decided that the “excitement of the bushwhacking there suited [us] finely…”11 They dressed and acted as bushwhackers and in the process of completely fooling everyone, in the process learning of guerrilla camps and leaders whereabouts, finally after listening to a guerrilla leader tell his stories of his acts against Federal troops, they shot the man in the head and headed back north.12 However, in contrast, General William Tecumseh Sherman admonished those who would fight for excitement at a speech he gave in Columbus, Ohio on August 11, 1880 to fellow veterans of the war;

There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory, but, boys, it is all hell. You can bear this warning voice to generations yet to come. I look upon war with horror, but if it has to come, I am there.13

In Missouri, fighting out of excitement found itself confronted with a less patriotic overtone, but nonetheless violent and merciless as those fighting against them. Some of these young men, who rode with guerrilla bands initially out of excitement or for seeking revenge, became neurotic and criminal. Richard Brownlee explains that “the irresponsible and undisciplined nature of guerrilla service naturally attracted the worst element of border society as it gave opportunity for robbery and unwarranted cruelty not present in regular military duty.”13 As a member of Quantrill’s Raiders, Harrison Trow recounts that, “As strange as it may seem the fascination of fighting under the black flag…attracted a number of young men to the various guerrilla bands.”15

To continue to Part 4 click HERE

Of the following, which group do you believe was more dastardly?

[1] Bruce Nichols, Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, Volume 1, 1862, (Jefferson: McFarland and Co., 2004), chapter 5.

[2] Samuel S. Hildebrand, Autobiography of Samuel S. Hildebrand: The Renowned Missouri Bushwhacker and Unconquerable Rob Roy of America Being His Complete Confession, edited by James W. Evans & A. Wendell Keith, (Jefferson City: State Times Book and Job Printing House, 1870), chapter 1.

[3] The Civil War, directed by Ken Burns, performed by Shelby Foote, 1990, episode 1.

[4] Thomas Goodrich, Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861-1865: A Riveting Account of a Bloody Chapter in Civil War History, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 7.

[5] Nichols, Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, Volume 1, 1862, chapter 5.

[1] James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought The Civil War, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), chapter 2.

[6] Missouri Division Daughters of the Confederacy, Women of Missouri in the Civil War, (Jefferson City: Big Byte Books, 1920), Kindle Edition.

[7] William J. Hoyt, Good Hater: George Henry Hoyt's War on Slavery, (Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, Inc., 2012), 11.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 51.

[10] Ibid., 182.

[11] Ibid., 182.

[12]Gerald Tebben, "Columbus Mileposts: Aug. 11, 1880: Even if ‘war is hell,’ Sherman didn’t say exactly that in his famous speech," The Columbus Dispatch, August 11, 2012.

[13] Richard S. Brownlee, Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861-1865, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984), 62.

[14] Nichols, Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, Volume 1, 1862, chapter 5.