- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

African-Americans In The American Civil War

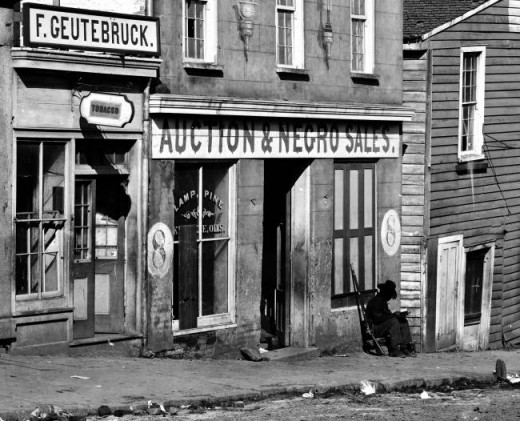

When Slavery Existed On The High Street

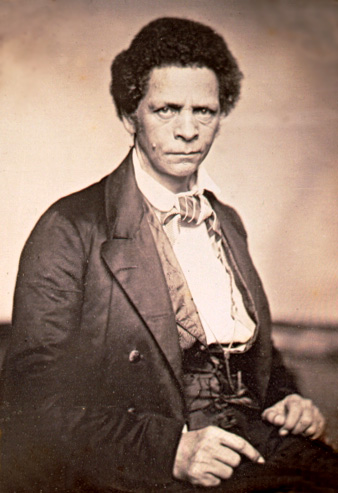

Liberia's First President

Background

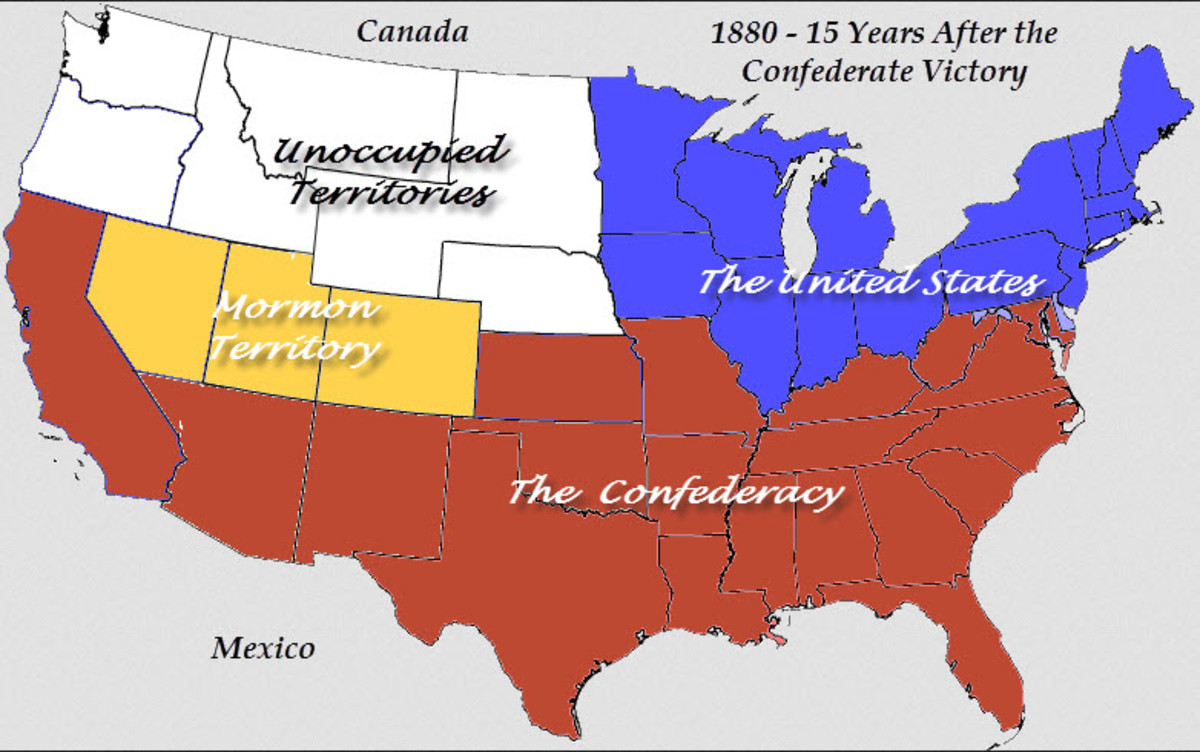

Right from its founding in 1818, the American Colonisation Society strove to send freed slaves and freed blacks from the North to foreign shores, in particular Liberia. The reason for this was that it was believed, not only by stakeholders, but also by some abolitionists, that blacks and whites could not ultimately coexist in the United States. The only successful colony was Liberia in West Africa, which became an independent state in 1847. Abraham Lincoln himself was a known proponent of colonisation before issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and supported several schemes during the war, most of which ended in tragedy for the emigrants.

Before the war, only Massachusetts legally extended full voting rights to its black citizens. Some other New England states allowed black male suffrage, and in New York those with $250 worth of property could vote. To have a vote in Ohio, over half a citizen’s ancestry had to be white. No other state allowed black people to vote.

During the war, some gains were made in civil rights. Blacks could ride alongside whites in Philadelphia and Washington streetcars and in 1864 they were allowed to appear as both witnesses and lawyers in federal courts, but further reforms would have to wait for the 14th Amendment.

Where Is Liberia?

The Full History Of Slavery In America

Union Policy

Union policy towards slaves and escaped slaves in the rebellious states wavered between decisive, proactive measures and lethargic inaction or neglect. Overall, the government was slow to implement a coherent policy. The Union army, U.S. Treasury Department, various philanthropic organisations, the President, and Congress all got involved and had different, often competing proposals and procedures on how to deal with the number of freedmen (freed slaves) or soon-to-be freedmen. Power ultimately rested with the military officers in any given area, and as early as the summer of 1861, Union commanders were confronted with large numbers of escaped slaves who had to run to safety within their lines.

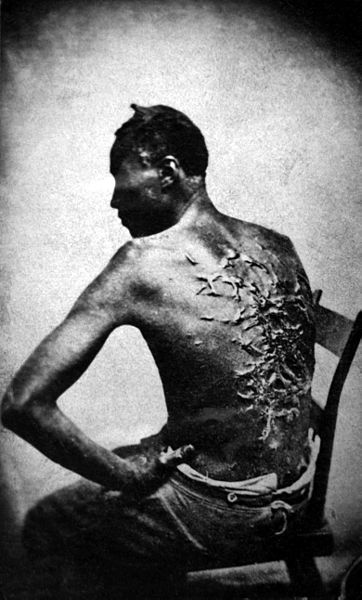

Permanently Scarred

Horrors Of The 'Contraband' Camps

These early refugees from slavery became known as ‘contraband of war,’ a phrase coined by Brigadier General Benjamin Butler, commander of Fortress Monroe in Virginia. It meant that the slaves did not have to be returned to their owners as fugitives under federal law. However, their fate varied considerably from one theatre of war to another.

Many of the former slaves were rounded up and placed in special ‘contraband camps,’ where sanitation was poor and medical care even worse. Death rates were as high as 25 per cent, and despite the presence of well-meaning missionaries, who provided spiritual and educational guidance, life in the camps was miserable.

In 1861-63, the camps followed the advances of the Union armies, and as time wore on, conditions improved slightly as Union officers found employment for large numbers of contrabands. The men worked as dockworkers, pioneers, trench-diggers, teamsters, and personal servants. Also, some of the women served as cooks and laundresses for the soldiers. In such capacities they performed the same functions as slaves did for the Confederate armies, but at least they earned a ‘wage,’ even though this could simply be room, board, and clothing. The families of the employed lived in the local camp or precariously hung around the margins of the Union picket lines.

Highly Recommended Links

- African-Americans In The Civil War

A look at African-Americans in the American Civil War- exploring both the military and domestic roles. - How Slavery Really Ended in America - NYTimes.com

An interesting and detailed article that explores exactly how slavery in America came to an end. - Voices from the Days of Slavery, Audio Interviews (American Memory from the Library of Congress)

An interesting website that gives you the chance to hear what life was like as a slave from former slaves themselves.

Wage Slavery Under The Unionists

Marginally more fortunate were former slaves on abandoned plantations that the Unionists confiscated and returned to working order. Early in the war, the Union army overran some of the South’s best plantation districts, including the Sea Islands off Charleston, southern Louisiana, and the fertile lands of the Mississippi River Valley. Owners ran to safety behind Confederate lines and simply left their land and slaves to their fate.

Realising the potential profits to be had, Northern civilian entrepreneurs responded eagerly to the federal government’s offers to manage these plantations. In theory, the government would receive the lion’s share of the sale of cotton, sugar, or other staple crops, and the former slaves would be paid a fair wage. In reality, plantation managers and local Union army officers conspired to split most of the profits among themselves, and often paid the labourers just enough to keep them working. After ‘deductions’ for food, housing, and clothing, most earned absolutely nothing, and therefore lived an existence akin to slavery. Local military laws that forbade blacks from being unemployed forced many of them back into the cotton or cane fields, or otherwise face imprisonment.

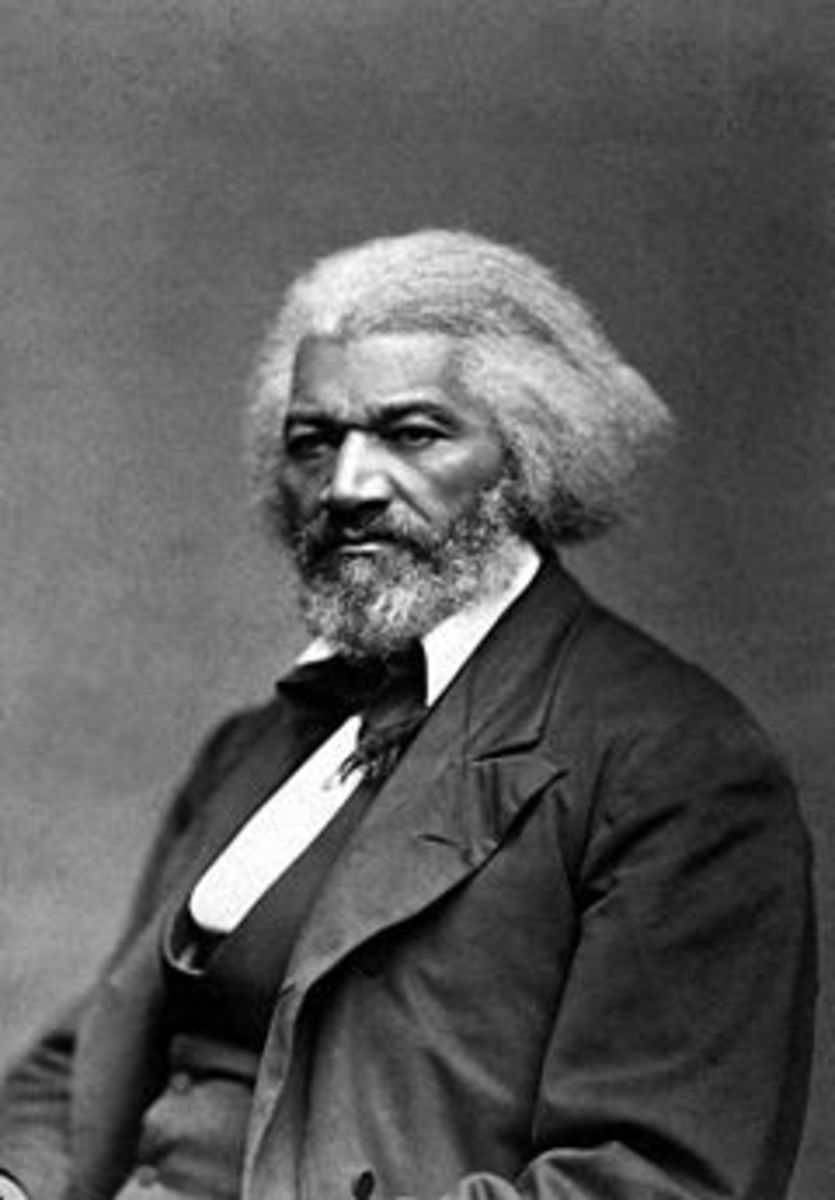

By the last 18 months of the war, under pressure from both Northern abolitionists and missionaries who were outraged at the ‘wage slavery’ that existed in the Union-occupied South, both Congress and the Union army began to change their policies. Land was the key issue behind this new direction.

Through various pieces of legislation, or under the supervision of Yankee generals, almost 20 per cent of the former Confederate territory captured by the Union was given to African-Americans. The prominent abolitionist Wendell Phillips wrote, ‘Let me confiscate the land of the South, and put it into the hands of the black and white men who fought for it, and I have planted a Union sure to grow as an acorn to become an oak.’ However, the question remained whether the freedmen would be able to hold on to any land they had gained after the war was over.

Toiling In the Fields

A Documentary About African-Americans Who Fought For The Confederacy

Black Confederates

The vast majority of blacks under Confederate control were slaves who, either by coercion or suggestion, remained on plantations or farms until liberated by invading Union forces. It is difficult to determine how many wished to stay with their masters, serving in the army as servants, teamsters, or labourers, or remain at home as fieldworkers and house servants. Few Confederate enlisted men owned slaves and so never brought them along to war; a sizeable percentage of officers, especially early on in the conflict, did bring a slave with them, but this declined significantly as the war dragged on. As an institution, slavery was irrevocably weakened after the Emancipation Proclamation, and by the last year of the war, many slaves, even those in unconquered areas of the South refused to work, or had no incentive to do so, as the majority of white men had left home. White female or black overseers, increasingly common by 1864, could not maintain discipline, and as slavery began to die so, too did the remaining economic power of the Confederacy.

Escape To 'Freedom'

Too Little, Too Late

As the Confederate army lost more and more fighting men, the idea of enlisting slaves into the ranks was finally accepted by the Confederate Congress in Richmond. However, prior to this certain Rebel generals including Richard Ewell, Patrick Cleburne, and ultimately, Robert E. Lee, proposed at different points in the conflict that the Richmond government grant freedom in return for slaves’ military service. Even President Davis offered a bill in November 1864 extending emancipation to future enlisted slaves, but Congress refused to consider it.

By February 1865, facing imminent defeat, and with the powerful backing of both Lee and Davis, the Congress grudgingly agreed to a limited form of emancipation for slaves who fought. Some companies of black Confederate soldiers were actually drilling in the streets of Richmond right before the city fell, but it was too little, too late.