- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

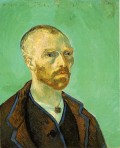

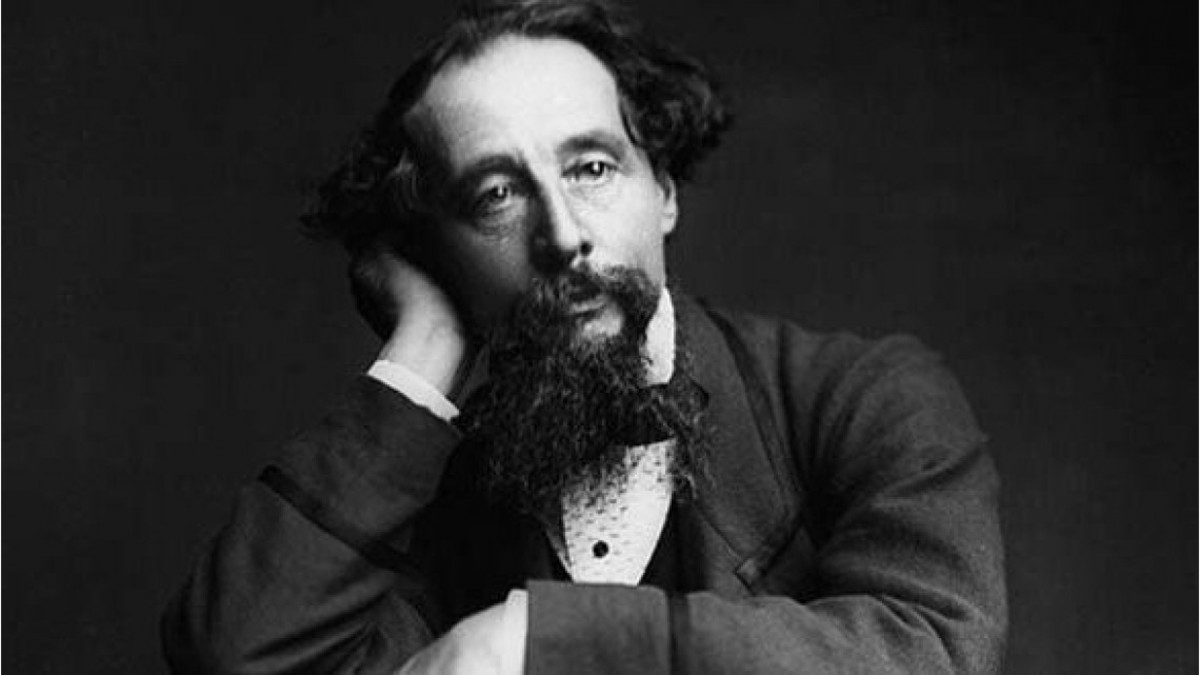

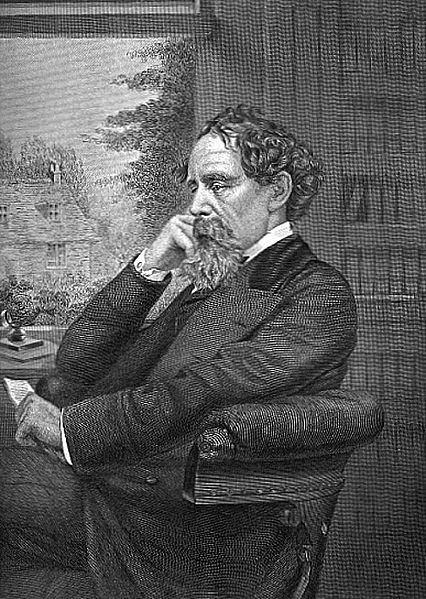

Five Interesting Facts About Charles Dickens That You Probably Didn't Know

The year 2012 marks the bicentennial of the birth of Charles Dickens, one of the world's best-loved storytellers. Every few years, it seems, one work or another of his is being revived through some sort of theatrical film or a new production on Broadway, to the delight of audiences far and wide. Though Dickens wrote in part during the Romantic period, his works are anything but romantic as he takes us through the seamy underbelly of Victorian life, through the orphanages and workhouses, populated by vast arrays of colorful characters with such unlikely names as Martin Chuzzlewit, Uriah Heep, and Wackford Squeers.

We know about the Ghost of Christmas Past, about Madame Defarge and her knitting, and about the dangers of not being satisfied with one's normal helping of gruel. Here are some fun and interesting facts about Charles Dickens that you probably didn't know.

1. His Early Life Was Dickensian

The universal rule for writers, which has been passed down from time immemorial, is "Write what you know," and Charles Dickens was no exception.

He may not have been an orphan like Oliver Twist, but he certainly knew his way around a workhouse. When he was 12 years old his father went to debtors' prison in Marshalsea and to help make ends meet, Charles was sent off to a factory in Hungerford Stairs where they made blacking -- what today we would call shoe polish. The factory was a pretty horrible place to work, with its rotten floors and stairs and its thriving colony of rats living down in the basement that according to Dickens could be heard at all times. He got in at least one fight while he was there. But he obviously got inspiration there, too. One of the boys working with him was an orphan by the name of Bob Fagin, whose name Dickens borrowed -- and ultimately immortalized -- years later when creating his sly master of the art of pocket-picking.

Dickens didn't take all of his inspiration from London's seamy side, though. As an adult he liked to vacation in Broadstairs, a fashionable beach community. One house, which in Dickens' day had sheep grazing in front, was supposedly the inspiration for the home of Betsy Trotwood. Another house known as the Fort House may have been the inspiration for Bleak House and has since been known by that name. Whether the actual inspiration or not, Bleak House certainly got Dickens' creative juices flowing. He started writing that novel while staying in the house and also finished David Copperfield there.

2. A Christmas Carol Wasn't His Only Christmas Work

The tale of Ebenezer Scrooge encountering Marley's Ghost is certainly one of Dickens' best-known and best-loved stories, but it was only the first of many tales that Dickens would spin for the Christmas season.

In those days, Dickens was known to the public largely through serialization -- delivering his novels through magazines, typically in 32-page installments. One magazine, Household Words, was a weekly publication which he controlled. (He later set up another one called All the Year Round.) As a result of his serializations Dickens developed a following, and after A Christmas Carol ran successfully in 1843, the public clamored for more. His Christmas offerings would become near-annual events for almost twenty-five years.

He published The Chimes in 1844 and The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845. Both of these works were novellas, which were followed by The Battle of Life in 1846 and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain in 1848, also novellas. As Dickens got busier, though, he could only fire off a short story for the holidays, which he did more or less every year from 1850 to 1867. One of the reasons he was so busy was that he often went on tour promoting his books and reading from them, in part because of the success of A Christmas Carol. He was the first major author to do so. Nowadays, of course, tours and readings by authors to promote their books are de rigeur.

3. He Was an Amateur Actor

Dickens' sense of the theatrical extended far beyond dramatic readings. He had long expressed a desire to be an actor, and while he never was one professionally, he was no stranger to the footlights.

His participation in amateur theatrics goes back at least as far as 1845, when he appeared as Captain Bobadil in a production of Ben Jonson's Every Man in His Humour at Miss Kelly's Theatre in Soho. In 1851 he performed in Not So Bad As We Seem for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. One of his favorite roles seems to have been that of Richard Wardour in The Frozen Deep written by his friend Wilkie Collins. In 1857 he and Collins staged a production of it in Dickens' home, Tavistock House, the theater having been converted from his children's schoolroom. Collins acted in the production, too, playing the part of Frank Aldersley, and Dickens' daughter Kate and son Charles also had roles. Tavistock House was used for other productions as well, billing itself as "The Smallest Theatre in the World."

In addition to being good at theatricals, Dickens was also an accomplished magician. One trick he liked to perform before friends at Christmastime was making plum pudding in a man's hat.

What the Dickens?

4. Marital Difficulties Nearly Destroyed His Reputation

By 1857, Charles Dickens had become one of the most famous men in the world. He had already published, through serialization, some of his greatest novels: Oliver Twist by 1839, David Copperfield by 1850, Bleak House by 1853. He was on the reading circuit and had a public who adored him. Careerwise, he couldn't have been doing better.

On the home front, though, his life was a mess.

By that time he had been married to his wife Catherine for twenty-three years, and while she was never as intellectually gifted as he was, she had borne him nine children and was by all accounts a loving wife and devoted mother. Somewhere along the way, however, Dickens seems to have come to the conclusion that this wasn't enough for him and that he and Catherine -- whom he called Kate but also his "dearest pig" -- were simply unsuited for one another both temperamentally and intellectually. While he couldn't bring himself to divorce her -- such a course of action was still largely taboo in those days -- he did manage to convey his displeasure with her by moving out of the bedroom that they shared into an adjoining dressing room and had carpenters seal up the passageway in between. It wasn't long before Catherine got the hint and moved out of the house.

Once London got word of Catherine's departure, it put Dickens in a new light -- one that was not at all favorable. He may have been a great storyteller, but sending his wife away apparently because she had done nothing more than lose favor with him made him look like a cad or worse. (His daughter Kate said in her opinion her father was a very wicked man.) Nearly everyone who knew anything about the situation took Catherine's side. It certainly didn't help matters that Catherine's younger sister Georgina, whom Dickens did seem to have some affection for, continued to live with Dickens and look after eight of his children, or that rumors were flying about concerning his relationship with an actress he had met through one of his theatrical ventures. (There actually was an actress as it turns out, a woman by the name of Nelly Ternan, who among other things may have been the inspiration for Estella in Great Expectations. But if her relationship with Dickens had become physical -- and Dickens scholars are divided as to whether it ever did -- it probably hadn't happened yet.)

In any event, Dickens realized that he suddenly had a public relations problem on his hands and tried to explain himself to his fan base through an address in Household Words. As often happens in such situations, he said he didn't wish to provide details and insisted on keeping the matter private. Unfortunately all this tactic did was add kerosene to the fire. Dickens then set about creating a much longer letter -- a scathing one in which he falsely accused his wife of being mentally ill and an unfit mother -- which he gave to his manager with the understanding that it would be shown to people only on a need-to-know basis. Inevitably that letter got leaked to the press, who in true British tradition promptly gave Dickens a thorough shellacking.

Somehow, though, Dickens managed to ride out the storm without too much erosion in his popularity, although after a settlement was reached for Catherine's support, the two of them never spoke to each other again. Catherine may have had the last word, though. Just before her death in 1879 she turned some of the letters Dickens had written to her over to Kate with instructions to give them to the British Museum -- proof, as Catherine put it, that her husband had loved her once.

5. He Was in a Train Wreck

In contrast to Dickens' marital situation, one train wreck he did manage to survive took place on June 9, 1865. He had been returning home from Paris with Nelly Ternan and her mother on a line of the South Eastern Railway when, at a little after three o'clock in the afternoon near Staplehurst in Kent, the train jumped a section of track that was still under renovation and took most of its cars down into the Beult River. Ten people were killed and 40 injured. Dickens' car was one of the few that didn't end up in the water.

Dickens was generally regarded as a hero for his assistance during the tragedy, helping to pull some people from the wreckage and comforting the dying. Most Dickens scholars note, however, that he was never quite the same afterward. While he had once been quite the prolific writer, the only novel he completed after the accident was Our Mutual Friend, which he had been working on at the time. He also wrote a short ghost story called "The Signal-Man," which was based in part on the incident, and began work on The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which he never completed. His literary life at that point was largely over. He died on June 9, 1870, precisely five years to the day after the Staplehurst crash.